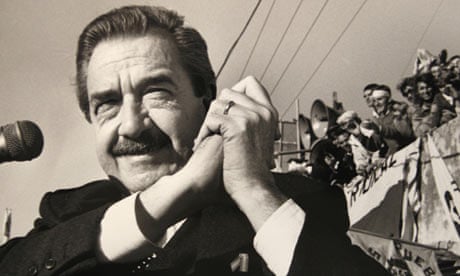

Raúl Alfonsín Foulkes, who has died aged 82 of lung cancer, became president of Argentina in 1983 amid the wreckage of the military regime's so-called "process of national reorganisation". The bloody, seven-year dictatorship, with its toll of at least 9,000 disappeared prisoners, had failed to survive defeat at the hands of Britain in the Falklands war and was forced to hand power to an elected, civilian government.

Unlike the Pinochet dictatorship in neighbouring Chile - which would last another seven years - the Argentine generals were unable to control the terms of their departure. Although later events would show that they were down, but not out, Alfonsín took advantage of their temporary weakness to put all nine former junta members on trial for human rights abuses.

So it is somewhat ironic that, rather than launching the country on a virtuous cycle of democratic consolidation and economic growth, the apparently well-meaning new president was himself eventually forced into a premature departure. By 1989, hyperinflation and food riots threatened to bring down his administration in a sequence of events that in some ways foreshadowed the collapse, 12 years later, of the De la Rúa government.

Alfonsín was 56 when he assumed the presidency. Born in Chascomús, a small town in Buenos Aires province, he was the son of a well-off Spanish shopkeeper and his British wife. After going to military academy, he took a law degree at the University of La Plata, founded a local newspaper and went into provincial politics with the Radical party (UCR), the main rivals to General Juan Perón's Justicialistas. In the mid-1950s, he was briefly imprisoned by the Perón government.

By 1963 he had been elected to congress, although his term was interrupted by a military coup in 1966 (as it would be again in 1976). Alfonsín was on the left wing of the UCR and led a minority group within the party called the Renovation and Change Movement.

During the 1976-83 military dictatorship, he co-founded the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights and spoke out against the crimes of the generals, including the abduction of leftists by the security forces. He was also one of the few politicians who publicly criticised the decision by General Leopoldo Galtieri to invade the Falkland Islands in April 1982.

In the elections of October 1983, Alfonsín won a clear victory over the Perónist candidate, Italo Luder. "Public immorality has ended," he declared confidently on taking office six weeks later. His aim, he said, was nothing less than the creation of a modern democracy that would finally end decades of political instability, punctuated by military dictatorship.

To give him his due, Alfonsín did achieve the first peaceful handover from government to opposition since 1928. He set up the National Commission on Disappeared Persons (Conadep), which compiled the internationally acclaimed Never Again report on the dictatorship's human rights abuses. A plebiscite led to the resolution of a longstanding dispute with Chile, and his government's literacy plan won a Unesco prize.

The military, however, soon bridled at the ignominy of being submitted to the civilian justice system. Under severe pressure from the armed forces, Alfonsín introduced the so-called Full Stop law in December 1986, requiring all new cases to be presented before a court within 60 days. The unintended effect was a quadrupling of cases virtually overnight, and an uprising the following Easter by the rebel Lieutenant Colonel Aldo Rico.

The Rico rebellion forced the introduction of a further legal limit, the Due Obedience law, which restricted legal responsibility for human rights abuses to just 84 senior officers. President Carlos Menem would eventually pardon all of them, as well as those involved in the Rico uprising.

On the economic front, the results were worse. Alfonsín had inherited large foreign debts and debt-ridden state enterprises. By June 1985, annual inflation had hit 1,200%. The president introduced an austerity programme, named after the new currency - the austral - with which he replaced the peso. For a while, the plan seemed effective, if harsh. But inflation, which had fallen to a mere 100%, soon began spiralling out of control again.

In the September 1987 congressional elections, the UCR lost its parliamentary majority. A major constitutional reform plan, which included a proposal to move the federal capital to Patagonia in an attempt to decentralise the state, had to be shelved for good.

The Alfonsín government struggled on until mid-1989. Menem, who had already won the presidential election but was not scheduled to be sworn in until December that year, was waiting in the wings. A quarter of the population - in a country that had grown accustomed to relative prosperity - was said to be living in poverty. Inflation had soared beyond 4,000% and supermarkets had been looted by rioters.

Power cuts, factory closures and layoffs were the stuff of daily news bulletins. Under pressure to hand over power early and avoid further violence, Alfonsín eventually capitulated, telling the nation on television: "No president has the right to endlessly demand sacrifices from his people." The inauguration of the Menem government was brought forward to 8 July 1989, and Alfonsín left the Casa Rosada presidential palace five months ahead of schedule.

Unlike De la Rua, however, he continued to command the respect and affection of many of his fellow Radicals. As a senator and UCR leader, he became one of Argentina's elder statesmen. When President Cristina Fernández unveiled a bust of him in the presidential palace last October, she told him: "Whether you like it or not, you are a symbol of the return of democracy."

He is survived by his wife, Maria Lorenza, three sons and three daughters.