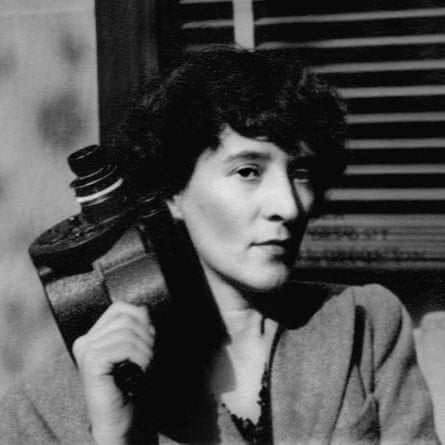

The American poet and cultural critic David Levi Strauss memorably described Helen Levitt as “maybe the most celebrated and least known photographer of her time”. That was in 1997, when Levitt was 84 and the subject of a retrospective at the International Center of Photography in New York, the city in which she was born and made most of her work. Just over two decades on, and 12 years after her death, aged 95, in 2009, one could argue that little has changed in terms of her enigmatic status.

In a few weeks’ time, though, a more radical retrospective of Levitt’s work opens at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, having garnered much attention at the Arles photography festival in 2019. Titled In the Street and curated by Walter Moser, art historian and chief curator for photography at the Albertina Museum, Vienna, it suggests that almost everything you know about Helen Levitt, if indeed you know her at all, is wrong.

“For too long, there had been this received notion that Levitt’s photographs are lyrical and poetic, words that are too often applied lazily to the work of female photographers,” says Moser, who has spent years researching Levitt’s archive and, in the process, discovered many previously unseen images. “The truth is that Levitt was part of a highly intellectual cultural and political milieu in New York in the 1930s and her photography reflected her deep interest in surrealism, cinema, leftwing politics and the new ideas that were then emerging about the role of the body in art.”

Over two floors in the Photographers’ Gallery, which, incidentally, hosted Levitt’s first European exhibition in 1988, In the Street will trace her work in photography and film over 50 years of restless, inquisitive looking. The world she observed for most of that time was defiantly local – Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Bronx and Spanish Harlem – and yet recognisably universal in its capturing of the rhythms and gestures of children’s play and adults’ social interactions or solitary reveries. It is a dramatically different world to our own, the city streets teeming with children, who play with reckless abandon on stoops, waste grounds and vacant buildings.

Levitt was born in Brooklyn in 1913, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. Her interest in photography blossomed when, aged 18, and having dropped out of high school, she began working in the darkroom of a commercial portrait photographer. Five years later, she bought a secondhand 35mm camera and, in his illuminating catalogue essay for her retrospective, Duncan Forbes asks us to picture “a diminutive, determined figure striding out, daringly at first, from Bensonhurst in Brooklyn across the city, transforming herself as a modern woman through her desire to see things differently”.

That desire would take a few years to change itself into a singular and subtle vision of the New York streets that remains an intriguing counterpoint to the more combative images made by the mostly male practitioners who followed in her wake in the 1960s and 70s and have all but defined the term “street photography”. But on the evidence Moser has gathered from her archives, which includes previously unseen photographs, contact sheets and short films, the term “street photographer” barely does Levitt justice.

“She doesn’t just charge in like many male street photographers tend to,” says Siân Davey, a British documentary photographer whose quietly observational work explores the psychology of family, self and community. “Instead, in her pictures, you sense a particular quality of contact between her and her subjects. There is tenderness and an absence of ego that tells you what kind of person she was.”

Although Levitt was a quiet, solitary figure on the streets of New York, she was not a detached observer: rather, Moser says, she wanted her subjects to be aware of her presence and respond to it.

“What is evident from close attention to her contact sheets is that people are often presenting themselves in regard to the photographer opposite them,” he says. “They are knowing participants in her photographs – looking at her, smiling at her, flirting or striking a pose for her camera, though often she crops her photographs to take out these overt acknowledgments of her presence. On one level, her photography is essentially a performative exchange and that lends it a very contemporary resonance.”

Initially, though, it was her exposure to the social realism of the determinedly leftwing Workers Film and Photo League that shaped her early style. Through it, she absorbed the idea that photography was an agent of social change, while never quite committing herself to the communist cause as wholeheartedly as fellow photographer Lisette Model, who would later find herself on an FBI watchlist. “I decided I should take pictures of working-class people and contribute to the movements,” Levitt later said of that time. “And then I saw pictures of [Henri] Cartier-Bresson and realised that photography could be an art – and that made me ambitious.”

She met Cartier-Bresson in 1935, introducing herself at a talk he gave to the Film and Photo League and subsequently accompanying him on a day-long shoot despite initially being intimidated into silence by his presence. “He was an intellectual, highly educated,” she later recalled. “I was a high-school dropout.”

Her participation in the Film and Photo League also exposed Levitt to the work of avant garde film-makers from Europe and Russia as well as surrealist ideas and radical developments in contemporary dance that, as Forbes puts it, elevated “an aesthetics of corporeal transfiguration through movement and drama”.

These contrasting formal influences – the realist and the poetic – were central to Levitt’s way of seeing, both in her photography and in her later embrace of film-making. As her style matured, her photographs of children seem almost choreographed in their capturing of the gestures and glances of play. And, though often joyous, they frequently have a darker undertone: the children engage in combat games and pose as gangsters in homage to the Hollywood films of the time. In one image, a child recoils as if he has just been slapped in the face by the adult looming over him. “There is a hint of darkness in her work, but it is never overt,” says Brett Rogers, director of the Photographers’ Gallery. “In her photographs, she presents the street as an almost theatrical landscape where the smallest interactions and gestures are incredibly resonant.”

In 1938, Levitt met another toweringly influential photographer, Walker Evans, whom she also befriended. Evans introduced her to the writer James Agee, with whom she would collaborate on her book, A Way of Seeing, and several intriguing films, including In the Street and The Quiet One, a documentary about an emotionally disturbed African American child.

For all that, Levitt was an intensely private individual who gave very few interviews in her lifetime. We know that she lived alone in her New York apartment with a cat called Binky and that she suffered from Ménière’s disease, which causes hearing problems and dizziness. In old age, she said, perhaps only half-jokingly, “I have felt wobbly all my life”. Her work, it seemed, centred her and she pursued it with single-minded determination.

“For all the research I have done, her personality is a mystery to me,” says Moser. “I just could not figure her out. She was ambitious and knew what she wanted and she was certainly not shy, but to a great degree, she hid behind her work.”

She also expressed herself through her photography in often bold and prescient ways as when, in 1959, she began shooting in colour. The results still startle when you see her prints for the first time, the deep tonal richness of the reds and greens adding a heightened otherness to her street tableaux. A young girl, crouching spider-like beneath the gleaming green surface of a pristine car is a study in childhood reverie amid an adult world that seems even more extravagantly unreal. Sadly, most of her colour negatives were lost when her apartment was burgled in 1970, forcing her to shoot again on the same streets with renewed intensity of purpose.

In her later photographs, it is the unruly energy and makeshift nature of New York that resonates, the streets becoming less playful and more crowded and combative, her images less joyous as the decades pass. “In the work she made in the 30s and 40s, she is always representing people who occupy their own space in their neighbourhoods,” says Moser, “but, by the late 1960s, and more profoundly in the 1980s, you are seeing in her images the ways in which the city has become increasingly regulated by consumerism and capitalism. This, too, of course, has a real resonance for our times.”

The exhibition’s title is borrowed from her first film, In the Street, which she made in 1948 in collaboration with Agee and the poet and photographer Janice Loeb. It is a short, silent, incredibly evocative flow of images from the bustling streets of Spanish Harlem in the 1940s. The first words that appear on screen are: “The streets of the poorer quarters of great cities are above all a theatre and a battleground.” That comes close to capturing the particular atmosphere of Helen Levitt’s extraordinary body of work, if not its singularly expressive power. She was, and remains, a quiet genius of 20th century photography.