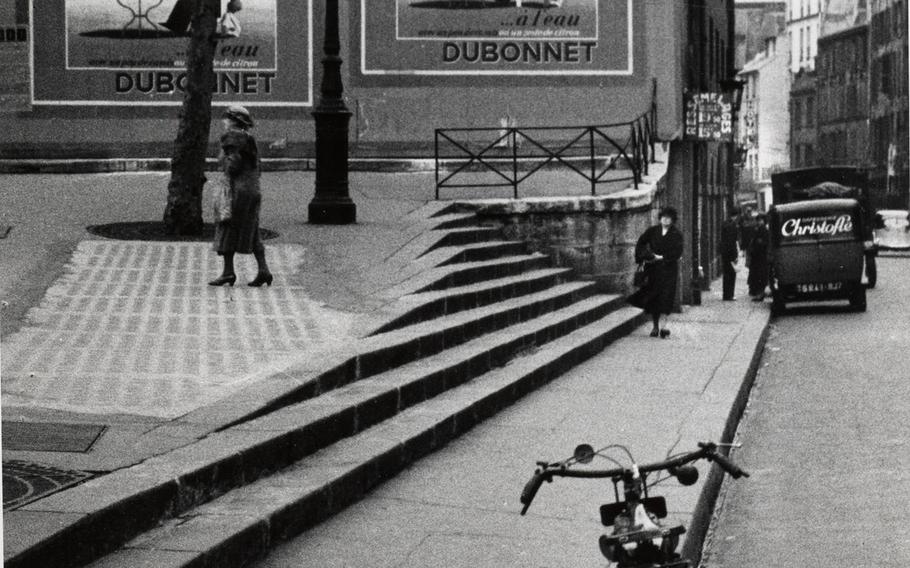

Hungarian-born photographer Andre Kertesz achieved maturity as an artist during the decade he spent in Paris, where he mixed with the great cultural figures of the time. This Paris scene, "Rue Saint-Denis'" (1934), is among photographs in the exhibit "Kertesz: Budapest - Paris - New York," which runs through June 12 at the Pfalzgalerie in Kaiserslautern, Germany. (Andre Kertesz/Courtesy of Museum Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, private collection)

Andre Kertesz, a giant among 20th-century photographers, spent his life in three of the world’s great metropoles. But throughout his long career he trained his camera on the poetic moments that could be found in the parks or backstreets of any minor city.

One such city is now playing host to Kertesz’s pictures. “Andre Kertesz: Budapest — Paris — New York,” an exhibit of more than 80 of his photographs, runs through June 12 at Kaiserslautern’s Pfalzgalerie. Some of his most famous works are here, including “Chez Mondrian,” a still life from the Paris studio of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, and “Underwater Swimmer,” a photograph from 1917 that reveals the photographer’s early fascination with the distorted human figure.

The pictures, all of them black and white, belong to a private collector in Berlin, who acquired many of them in the 1960s, before the photographer’s significance was fully appreciated. With its proximity to Paris and large American community, Kaiserslautern is an appropriate venue for an artist who made the French capital and New York City his second and third homes.

Born in Budapest in 1894, Kertesz belonged to an extraordinary generation of Hungarians who left a lasting impression on the arts and sciences. Its ranks included the physicist Edward Teller, the mathematician John von Neumann and the filmmaker Alexander Korda.

Hungarians found such success in the U.S. movie industry that a sign was posted in the MGM commissary: “Just because you’re Hungarian doesn’t mean you’re a genius!”

Kertesz, it turns out, was both. But despite the tremendous influence he exerted on the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Brassai (another Hungarian), he was late in receiving the recognition he deserved. In 1985, just months before his death, the critic Andy Grundberg suggested that the subtlety of Kertesz’s work might have been responsible for the critical and popular oversight.

“He delights in the ephemeral, the incidental and quotidian, in the half-hidden gesture, the brief blush of twilight, the juxtaposition of the new and the old,” Grundberg wrote in The New York Times. “He honors such incidents, invisible to most of us most of the time, with his full attention.”

Kertesz’s powers of perception are on full display in the Pfalzgalerie show, which follows his progress through the three stages of his career. The early photographs reveal a sensitivity to form that would become increasingly acute and subtle as he matured. One thing, however, would remain constant: his attitude toward picture taking. His gaze was always warm and curious, often affectionate or whimsical.

That warmth can be felt in his photographs of street life and village scenes in his native Hungary. Many of these resemble unselfconscious snapshots — simple compositions made with the camera aimed straight ahead. Some of them — with dramatic, cloudy skies — just skirt sentimentality.

One early photograph in the exhibit depicts a young girl in a field looking at a goat. The triangular shapes of rooftops in the background rescue this rather plain picture from the category of mere documentary photography.

Another picture from the same period, a view of the city of Esztergom, reveals a similar attention to geometry. No fluffy clouds hang over this scene; instead a scraggly, nearly leafless tree frames a shot of blurred buildings. This isn’t your standard genre picture, and yet it’s not quite a radical departure from pictorialism. But Kertesz’s sophistication is already evident. He makes a focus of what a less skilled photographer might have used as a decorative element.

To gauge how far Kertesz’s vision would evolve, walk into the second room of the exhibition space and look at a nighttime view, shot in 1958, of a building off New York City’s Washington Square. The photograph is almost completely black. Scores of lighted windows are the only indication there’s a building in the background; neither the outline nor the surface of the structure is visible. Against this backdrop is the skeleton of a massive tree.

This deceptively casual picture illustrates Kertesz’s unique achievement as a photographer: his appreciation of form, his impeccable sense of composition and his deep empathy. Here the pure abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky merges with a romantic, affectionate view of the big city.

Kertesz brought the same sensitivity to photographing people, though the Pfalzgalerie show doesn’t quite do justice to this rich vein of his work. None of his masterful nudes are on display here, nor will you see his lighthearted pictures of rooftop sunbathers. The exhibit — if not the collection — skews toward photographs that highlight Kertesz’s powers of abstraction: black spirals in a snow-covered park, a study in light and texture created by the flow of water along a street curb.

Nevertheless, we do get a sense of the magic he could work with the human figure in a close-up titled “My Mother’s Hands” (1919). This picture is an expression of love as well as a meditation on form. It calls to mind a magnificent photograph that’s not in the exhibit, “Elizabeth and Me” (1931), a portrait of Kertesz’s wife in which the photographer’s disembodied hand rests upon her shoulder. The same humor and sensuousness displayed in “Elizabeth” can be found in some of the still lifes in the Pfalzgalerie show, such as “Glass” (1943) and “Melancholic Tulip” (1939). These come closest to the eroticism of his nudes.

After settling in Paris in 1925, Kertesz moved in artistic and literary circles, and there are plenty of photographs at the Kaiserslautern show of friends at home and strangers in cafes. Next to the famous picture of Mondrian’s studio is one of Mondrian himself. The walls behind him form overlapping and vanishing planes that create the effect of one of his own paintings. It calls to mind the carefully framed environmental portraits of Arnold Newman, an American photographer a generation younger than Kertesz.

The appearance of people becomes rarer as the visitor proceeds through the New York photos at the Pfalzgalerie. Whether or not the selection here is representative of Kertesz’s artistic output at the time, it makes intuitive sense. Kertesz, who was Jewish, came to New York in 1936, after Hitler consolidated power in Germany and as fascist parties were on the rise elsewhere in Europe. He initially found America uncongenial, and the pictures in this period suggest an increasing inner retreat and a focus on his immediate surroundings.

Visitors to “Kertesz: Budapest — Paris — New York” will have a hard time understanding how Kertesz’s adopted hometown could have overlooked this Hungarian’s tremendous talent. His genius, now impossible to ignore, was that his penetrating eye never overlooked anything.

DIRECTIONS: Address: Museumsplatz 1, Kaiserslautern, Germany

TIMES: “Andre Kertesz” runs through June 12. Hours: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Tuesdays, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays, holidays.

COSTS: 5 euros for special exhibits (about $5.60), 3 euros for permanent collection. A combined ticket costs 6 euros for an individual, 10 euros for a family.

FOOD: The museum does not offer food, but it is a 5-10-minute walk to the pedestrian zone, where there are plenty of restaurants and stores.

INFORMATION: Website: mpk.de; email: info@mpk.bv-pfalz.de; phone: (+49)(0)631 3647-201