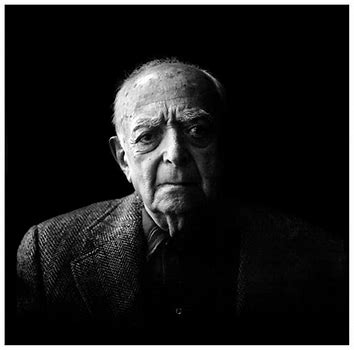

Brassaï

(1899-1864)

Brassaï: The Monograph

Wikipedia

Brassaï 9pseudonym of Gyula Halász) was a Hungarian–French photographer, sculptor, medalist,writer, and filmmaker who rose to international fame in France in the 20th century. He was one of the numerous Hungarian artists who flourished in Paris between the World wars.

In the early 21st century, the discovery of more than 200 letters and hundreds of drawings and other items from the period 1940 to 1984 has provided scholars with material for understanding his later life and career.

Brassaï (pseudonym) was born on 9 September 1899 in Brassó, Kingdom of Hungary (today Brașov, Romania) to an Armenian mother and a Hungarian father. He grew up speaking Hungarian and Romanian. When he was three, his family lived in Paris for a year, while his father, a professor of French literature, taught at the Sorbonne.

As a young man, Halász studied painting and sculpture at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts (Magyar Képzőművészeti Egyetem) in Budapest. He joined a cavalry regiment of the Austro-Hungarian army, where he served until the end of the First World War.

He cited Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as an artistic influence.

In 1920, Halász went to Berlin, where he worked as a journalist for the Hungarian papers Keleti and Napkelet. He started studies at the Berlin-Charlottenburg Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule für Bildende Künste), now Universität der Künste Berlin. There he became friends with several older Hungarian artists and writers, including the painters Lajos Tihanyi and Bertalan Pór, and the writer György Bölöni, each of whom later moved to Paris and became part of the Hungarian circle.

In 1924, Halasz moved to Paris, where he would stay for the rest of his life. He began teaching himself the French language by reading the works of Marcel Proust. Living among the gathering of young artists in the Montparnasse quarter, he took a job as a journalist. He soon became friends with the American writer Henry Miller, and the French writers Léon-Paul Fargue and Jacques Prévert. In the late 1920s, he lived in the same hotel as Tihanyi.

Miller later played down Brassai’s claims of friendship. In 1976, he wrote of Brassai: "Fred [Perles] and I used to steer shy of him - he bored us.” Miller added that the biography Brassai had written of him was typically "padded,” “full of factual errors, full of suppositions, rumors, documents he filched which are largely false or give a false impression.”

Halász’s job and his love of the city, whose streets he often wandered late at night, led to photography. He first used it to supplement some of his articles for more money, but rapidly explored the city through this medium, in which he was tutored by his fellow Hungarian, André Kertész. He later wrote that he used photography “in order to capture the beauty of streets and gardens in the rain and fog, and to capture Paris by night.” Using the name of his birthplace, Halász went by the “Brassaï,” which means “from Brasso.”

Brassaï captured the essence of the city in his photographs, published as his first collection in the 1933 book entitled Paris de Nuit (Paris by Night). His book gained great success, resulting in being called “the eye of Paris” in an essay by Henry Miller. In addition to photos of the seedier side of Paris, Brassaï portrayed scenes from the life of the city’s high society, its intellectuals, its ballet, and the grand operas. He had been befriended by a French family who gave him access to the upper classes. Brassaï photographed many of his artist friends, including Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, and several of the prominent writers of his time, such as Jean Genet and Henri Michaux.

Young Hungarian artists continued to arrive in Paris through the 1930s and the Hungarian circle absorbed most of them. Kertèsz immigrated to New York City in 1936. Brassaï befriended many of the new arrivals, including Ervin Marton, a nephew of Tihanyi, whom he had been friends with since 1920. Marton developed his own reputation in street photography in the 1940s and 1950s. Brassaï continued to earn a living with commercial work, also taking photographs for the U.S. magazine Harper's Bazaar. He was a founding member of the Rapho agency, created in Paris by Charles Rado in 1933.

Brassaï’s photographs brought him international fame. In 1948, he had a one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, which travelled to George Eastman House in Rochester, New York; and the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois. MoMA exhibited more of Brassaï’s works in 1953, 1956, and 1968. He was presented at the Rencontres d’Arles festival in France in 1970 (screening at the Théâtre Antique, Brassaï by Jean-Marie Drot), in 1972 (screening Brassaï si, Vominino by René Burri), and in 1974 (as guest of honour).

In 1948, Brassaï married Gilberte Boyer, a French woman. She worked with him in supporting his photography. In 1949, he became a naturalized French citizen after years of being stateless.

Brassaï died on 8 July 1984 at his home on the French Riviera near Nice. He was 84 years old.

Excerpts

“It is not easy to describe Brassaï many-sided personality; he was a collector, scholar, lively raconteur, draughtsman, photographer, sculptor, writer and a minute observer of ‘man’s strange customs.’ But he was also a reserved man who saw his private life as his alone, and believed that books gave all the autobiographical information that was necessary. He hoped that “his work would remain to some extent anonymous,’ at least during his lifetime, allowing him to reveal as much as he wanted about himself gradually, simply through his books.”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 151

“He gives the impression of a vivid intelligence, warmth and vitality, a ‘high voltage’ man… Those who knew him recognized him as ‘astute, reserved and creative,’ warm, sociable… free and independent… a genuine artist, living for his art and going his own way.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 151

“Foremost among those who inhabited the world of his imagination was Goethe. Brassaî’s thinking was deeply influenced by him, and he read and reread him constantly, writing out the following passage many times over: ‘My determination to see and understand all things just as they are, my unchanging reliance on my own eyes to illuminate them, my care to strip away all personal considerations, have all gradually made me very happy… Little by little, objects have raised me to their own level.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 151

“Brassaï chose to call himself a ‘creator of images,’ adding that: ‘Just as a poet reclaims overused words, the creator of images also challenges everything that has become too familiar. He wants to restore the power of the ordinary, disregarded things, to surprise us with what we are tired of seeing every day, or which though habit we no longer even notice; for me, this is the role of a ‘creator of images.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 151, 152

“In [letters to his parents] Brassaï reveals a complex and energetic temperment: ‘I have hundreds of faces I can use to conceal my real self and every person I meet knows a different mask. I have long since rejected everything peaceful and quiet—everything mean, mediocre and ordinary… I am not interested in a boat trip around the coast, however idyllic—and above all, however peaceful and quiet—it might be. What I want is the ocean with its crested waves and deep troughs.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 152

“He analyses himself perceptively, and is already aware of the many contradictions and insoluble interior conflicts to which he will be subject all his life. ’I have had to accept that alongside the artist, and independently of him, I harbour another self that I could call a thinking or a philosopher self. After the artist had managed to make himself heard during their first bout, I was obliged to admit the force of my other self’s claim to equal rights. These two roles each demand undivided attention, and do not coexist comfortably; however, in my case I am usually able to keep them apart. As soon as one of them is quiet—as soon as I stop reacting intuitively—the other, with its inexhaustible thirst for knowledge, takes over. And in this way one alternates constantly with the other.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 152, 153

“He recognized in Kertéz the two qualities he would always consider essential for a great photographer, ‘an insatiable curiosity about the world, life and mankind, and an acute awareness of form.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 153

“Brassaï knew how to see the hundreds of insignificant details of daily life… Beyond that simple reality, one of Brassaï’s most startling abilities was to make us aware of the indefinable transience of things…”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 153, 154

“‘Night only suggests things, it doesn’t fully reveal them. Night unnerves us, and surprises us with its strangeness; it frees powers within us which were controlled by reason during the day… I loved the way the night’s apparitions hovered on the edges of the light…’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 157

“‘I became a photographer in order to capture the beauty of streets and gardens in rain and fog, and to capture Paris by night.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 157

“‘A creative person is finally born when he has found his own route and voice.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 157

“Although he rarely attempted to produce poetry in the strict sense, Brassaï always liked writing, and all his important albums are intended to be read as well as looked at, most of the texts by Brassaï himself… His prose writings… confirmed his interest in ‘eccentric, bizarre, unattached, individual people,’ who for him… personify ‘the magic of life, just as people who are no different from everyone else represent all that is most unattractive about it.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 158

“His writing shows a taste for the fleeting moment and a readiness to detail reality as it happens rather than making a literary interpretation of it. Brassaï the writer shows the same instinct to avoid all subjective treatment as Brassaï the photographer.

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 158

“[Paul Richard, Washington Post]: … his photographs are so stripped of personal ego that it is easy to forget entirely about the individual who took them. There is nothing to interrupt the direct communication established between the subjects of the photographs and the observer. It is as though they had somehow photographed themselves.”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 1588

“‘I dislike this laziness…I’ve had enougn of this! What}s the point of a life of simplicity and ignorance, without literature, real life or art?’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 159

“‘The surreal exists within us, in the things which have become so banal that we no longer notice them, and in the normality of the norma… People thought that my photographs were Surrealist because they showed a ghostly, unreal Paris, shrouded in fog and darkness. And yet the surrealism of my pictures was only reality made more eerie by my way of seeing.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 160

“… Brassaï undoubtedly went through many periods of development and change, constantly moving from one medium to another… often wondered how to describe his work.”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 161, 162

“… he both felt like and wanted to be not so much an artist as an enthusiast. He always disliked the terms ‘artistic photographer’ and ‘picture hunter’. He also rejected what he called ‘childish amusements’ such as double exposure or solarization…. He saw himself as a ‘sardonic and dedicated observer of the world, a plunderer of beauty of all kinds, a thief who with a clic of the shutter… captures the thing that has enthralled him’, and he saw curiosity in its most positive sense as his driving force.”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 162

“‘… a man specializing in one thing relegates himself from the ranks of artist to that of artisan. Success in any one area encourages and even requires exploitation of this success, making a profession as a specialist out of what had ben done for sheer pleasure as an amateur. The dilettante’s passion for an art will always be greater thatn that of the man with the gift of practising it, for the dilettante’s passion is like a hopeless love, for ever insatiable. All my life I have tried to preserve the amateur’s freshness of vision, coupling it very time with the knowledge and awareness of the professional: this is the reason for my constant changes of tack [media], the scope of my curiosity, and my many parallel skills… this apparent inconsistency has been my own logic.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 161, 163

“‘Isn’t it the case that each person’s life is like the delta of a great river, the branches representing all the possible directions our lives can take? Some of the branches remain narrow, flowing slowly, while others widen. But whichever channel it flows along, shouldn’t we accept that all the water comes from the same source, and is ultimately one river? In the end, I see no reason to regret that the widest branch of the river of my own life has been photography.’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 161, 163

“… he spent some twenty five years tracking down the graffiti on the black, encrusted walls of Paris made by ‘inadequtes’, ‘simpletons’, ‘misfits’, ‘rebels’, or abandoned children. He saw them as the most spontaneous expression of the great human themes: birth, love and death.”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 164

“‘Nothing is greater than reality itself; why wrap it up in our own confused emotions?’”

Brassï: the Monograph; “Letting the eye be light,” Annick Lionel-Marie; p. 164

“Yves Allégret has given me a camera; I’ll try it out. I feel sure of succeeding straight away. I will find things by chance, without any preconceived ideas, without a script, just people going about their business. I will make sets of images without a particular theme. They will have nothing in common but the eye which saw them, and be bound together by life more securely than be even the cleverest script.’”

Cahier jaune (journal: Paris 11/1/36); Brassaï; p. 167

“I would have been wrong not to agree to doing this catalogue, because one always learns something from this kind of work, and photographing things for a catalogue is a (hard) lesson in humility. There is no place for telling stories or playing the ‘artist’, it’s only about the object, clearly shown, nothing but the object for what it is. I can’t say that it makes my heart beat faster to photograph a cigarette lighter, bit if I do it well, at least I can be pleased with a workmanlike job, producing from reality an image that does it justice, or even improves on it; it really is hard to make a good photograph of a cigarette lighter!”

Cahier jaune (journal: Paris 11/16/36); Brassaï; p. 168

“I must get back to the plastic arts. This longing is becoming more and more of a physical need. Photography is really only a starting point. Even when completely successful, I am somehow not completely satisfied by it. It is choice and not expression. The process has its limitations, and although I know them, I accept them in all humility. I quite like being able to remain anonymous. After all, photography has allowed me to come out of the shadows by showing what I see…”

Cahier jaune (journal: Paris 3/6/37); Brassaï; p. 171

“The heavy responsibilities that go with having a talent become clearer. Photography has brought me out of the shadows, it has given me the momentum I needed. I must now make the best possible use of it, even if it means a change of direction.”

Cahier jaune (journal: Paris 6/27/36); Brassaï; p. 172

“If you want colour in a photo, I said to myself, you don’t want to start with the ‘subject’, even if it lends itself to the use of colour, because it will still be a ‘subject’ or ‘document’, but in colour; you must start with the colour itself, colours as such, and sometimes it will have the same feeling as a well-painted picture, even if the subject has not intrinsic interest at all, and is only a vehicle for the colour.”

Conversations with Henri Michaux¨; (2.21.64); p. 184

“‘For me too… this infatuation with seedy place and seedy youths was doubtless necessary. How else could I have snatched those few images from the strange nights of Paris in the thirties, before they were swallowed up without trace?’”

Brassaï and Literature; Roger Grenier; p. 207

“Every time he published an album of photographs, he had a compulsion to write something. It started with captions to accompany the photos, which soon expanded to become stories in their own right, so that these books are as much for reading as for looking at the pictures.”

Brassaï and Literature; Roger Grenier; p. 208

“Brassaï combines two qualities rarely found in one writer. He was a prodigious storyteller; but his narrative skill was matched by his philosophical cast of mind. Whether confronted by the loftiest or the most trivial expression of human life, he seemed to say: that too exists, and merits investigation.”

Brassaï and Literature; Roger Grenier; p. 211

“Photography, which is the very image of self-effacement, does also reveal the personality, but always indirectly, through the medium of an interposed world. That is why I chose it. But can it assuage all our hunger and thirst? I remember Picasso saying to me one day: ‘It is impossible photography will ever manage to satisfy you completely…’”

Transmutations; Brassaï; p. 214

“It is legitimate for a man who has given the best part of his life to an occupation of absorbing interest, to seek to justify his activity and to relate it to some broader aspect of life, either in the present or in the past.

But the difficulty is to find a name for what he considers his vocation. For though many names describe it, none exactly fits. Seen with a camera in his hand, he is called a photographer. Yet he possesses no studio, nor does he deal with portraits, publicity, sport of fashion.He does not indulge in documentary or scientific photography. Nothing would horrify him more than to be taken for a professional photographer—a specialist. Does that mean he’s an amateur? No, for he execrates the dilettantism which, for lack of technical skill, is incapable of expressing ideas, of communicating them with from and authority. A reporter, then? Does he rush off to the scene of an accident or a crime? Is he always on the look-out for unusual, spicy details? Doe he follow the travel or statesmen or the campaigns of generals? Does he go exploring or visit strange lands beyond the sea? Is he really anxious to witness and record the stupendous, the extraordinary? Why, No. He has the utmost distaste for ‘news’ and avoids it when possible. He dislikes travel and loathes sensationalism from the depths of his soul. The most thrilling event for him is daily life. But that is not to describe him as an illustrator, although his pictures do appear in albums and illustrated papers. But what do they illustrate? They don not at any event serve to adorn, explain or comment upon a text. They have captions, usually as clumsy as they are superfluous. It is rather a case of the text, reduced to its simplest expression, illustrating the photographs.

This man is sometimes said to hunt for pictures. But he hunts nothing at all. He is the quarry, rather, hunted by his pictures. Sometimes, flatteringly, they call him a poet. Then he gets frightened. Has he taken the wrong turning, he wonders? He has never looked at anything with an ulterior, poetic motive, and has always instinctively avoided what is usually known as poetry. Well, then, he must be an artist. An artist? He hates the very sound of the word when applied to photography. ‘Artistic photographer’! Horrible! He is not the man to shut himself up in an ivory tower to play with puzzle-pictures, or the chase after ‘against-the-light’ effects, luminous halos or stream-lined nudes. Nor is he interested in view-points from awkward angles, dizzy bird’s-eye views, or the world seen through the eye of a microscope. He has always shown a sovereign disdain for ’artistic’ effect, for the ’pretty’ or the ‘pictuesque’. He has never wasted his time with such childish amusements as super-impression, solarizations and other tricks, which, though legitimate from the technical point of view, are condemned utterly and absolutely by the rules of photographic art. He has never felt the itch to overstep the bounds, to ape the latest fads in painting, in order to prove that he, too, can invent, that he, too, has an imagination, and that photography, too, is Art (with a capital ‘A’).”

Preface to Camera in Paris; Brassaï; p. 280

“The photographer of this kind, who depicts the variety of human existence in the light of common day, interpreting the dominant traits of the living creature, the character of its surroundings or the intrinsic life of the group, is, therefore, accomplishing a task handed down to him by the great draughtsmen of the past and disdained by the artists of to-day. He has taken his camera in his hand because he has discovered an plunged into the heart of the life around him. He too culls the ephemeral beauty of the present moment. He too converts his chance encounters into lasting pictures. He too gives a semblance of durability to the brief moments captured in the flight of time. Like his great ancestors [painters, draughtsmen] he is an implacable spectator, an impartial witness and a faithful chronicler.

Preface to Camera in Paris; Brassaï; p. 284

Style

-

Themes

-

Plates (favorites)

My Opinions

~

Questions

~

Thoughts on Artists

“We have reached the point where we do not want to know any longer whose work it is, whose seal is affixed, whose stamp is upon it; what we want, and what at last we are about to get, are individual masterpieces which triumph in such a way as to completely subordinate the accidental artists who are responsible for them. Every man today who is really an artist is trying to kill the artist in himself—and he must, if there is to be any art in the future. We are suffering from a plethora of art. We are art-ridden. Which is to say that instead of a truly personal, truly creative vision of things, we have merely an aesthetic view.”

The Eye of Paris; Henry Miller; p. 175 (Brassaï’s photographs illustrated Miller’s writings)

“Most writers will know the huge importance a simple photograph can assume, how it can provide the germ of a story, inspire a poem, or jog the memory into recalling a whole other world or age.”

Brassaï and Literature; Roger Grenier; p. 210