I recently discovered a photograph of Jean-Michel Basquiat that has forever changed the way I think about him. The image isn’t the one of him from 1985, when he was 24 years old and at the height of his early art stardom, reclining barefoot in a dark Armani suit on the cover of The New York Times Magazine. Nor is it the one where he is shirtless with dreadlocks, sporting boxing gloves next to a fully clothed and specterlike Andy Warhol, as he appeared on a poster advertising their collaborative show, “Warhol, Basquiat,” at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo that same year. It isn’t even an earlier one taken in 1982 by the famed Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee, then 95, in which a young Basquiat is dressed in a plaid suit jacket, stroking a cat that’s sprawled across his paint-splattered jeans.

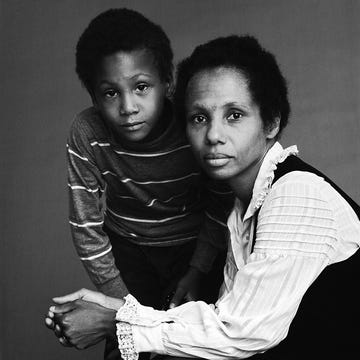

Instead, the internet gifted me with another Basquiat. In the photo I found, he’s dressed in a plain white T-shirt as he sits on a metal chair with his head pressed down against a table, mesmerized by what he’s drawing with his right hand on the paper before him. His left hand is tightly clasped around another pencil, while his tiny, unpicked Afro holds two more. Basquiat was 11 years old when the picture was taken, in 1972, by a teacher in his sixth-grade classroom at P.S. 101 in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. It would be another decade before he’d embark on his meteoric rise in the art world, on his way to becoming the most famous Black artist of his generation. The popular mythology surrounding Basquiat’s origin story—his journey from couch-hopping graffiti artist to the center of New York’s surging 1980s art scene—was cemented tragically by his death in 1988 at the age of 27 from a drug overdose. But what struck me most about this image of a preteen Jean-Michel lost in his own creativity and imagination is that it’s both evidence of and witness to another aspect of the Basquiat narrative: proof that his talent was not just prodigious but also recognized and even cultivated by the people closest to him early on.

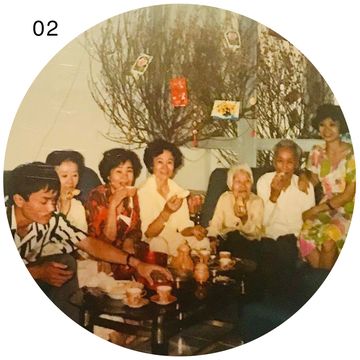

It’s this Basquiat who is the subject of the new exhibition “Jean-Michael Basquiat: King Pleasure©,” which opens in April at the Starrett-Lehigh Building in New York’s Chelsea gallery district. The show was assembled by his younger sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, who are co-administrators of his estate, along with their stepmother, Nora Fitzpatrick. More than 200 paintings and drawings from their private collection will be on view—many previously unseen—alongside a selection of photographs, personal artifacts, and multimedia presentations, including full-scale re-creations of the Basquiat family living and dining rooms. It’s also the first exhibition overseen by the Basquiat family, which has often been relegated to the margins of the conversation about his growth and evolution as an artist.

“King Pleasure©” will cover the course of Basquiat’s storied career and short life as well as offer a personal reflection on his legacy through the eyes of his siblings. By offering an unprecedented window into his formative years, the show also aims to upend the long-standing racial stereotypes that have frequently clouded his work and reveal the central role that his Puerto Rican and Haitian heritage and relationship with his Black family played in nurturing his creativity.

“Jean-Michel is so widely celebrated in so many different industries,” Lisane, the elder of his sisters, who was four years his junior, tells me. “We wanted to share a little more of the personal side of him with the world. And we’ve had these works in the warehouse for over 30 years, and people haven’t seen them.”

For Jeanine, who was seven years younger, putting together “King Pleasure©” has been cathartic. “It’s been a beautiful experience to recapture the stories of our family and our memories of growing up and Jean-Michel,” she says, noting that people often confess their shock when they learn that he had two sisters and a family with whom he kept in contact throughout his life. “We did have a relationship with him until he passed. And we’d like to add that narrative.”

“Jeanine and I really are the only two people who can tell this story,” Lisane says. “In some ways, it’s as much for us as it is for the public. It’s just a way of documenting this incredible character in our family.”

To help bring “King Pleasure©” to life, the sisters enlisted Ghanaian-British architect Sir David Adjaye. In structuring the exhibition, Adjaye, who along with Philip Freelon designed the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., sought to capture the fullness of Basquiat’s life in the show’s arc.

“What was deeply revelatory for me was understanding Basquiat as a member of his family. I just had him as a kind of solitary figure, disconnected from his family and everyone, sort of somehow going into the world as this haunted [individual]. But he actually was deeply connected to his family,” Adjaye says. “There is a sense that somehow his genius couldn’t come from his family, but he grew up in an intellectual family and was really stimulated by the various sophisticated ideas of the time. He didn’t just stumble on this. He was brought up in it.”

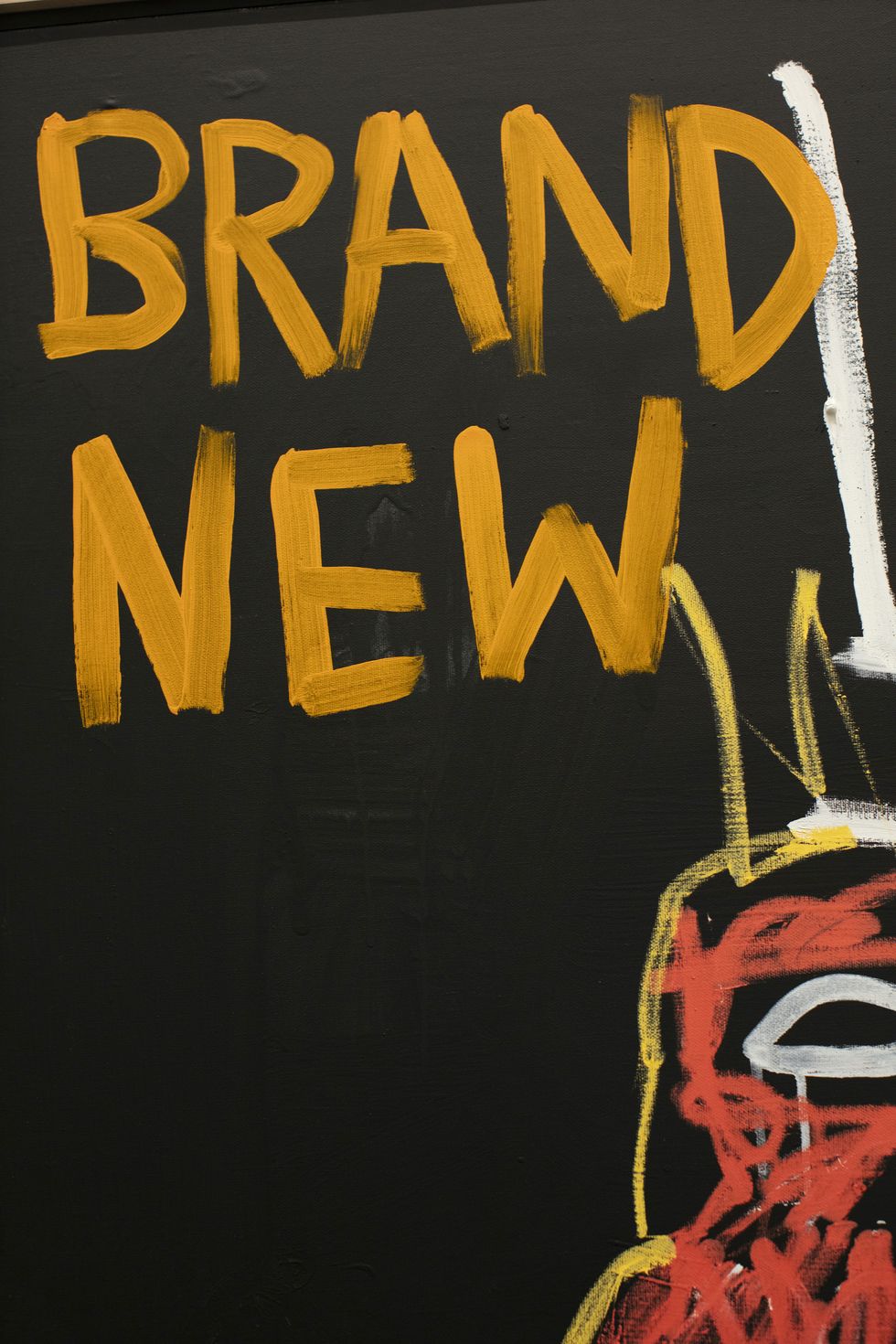

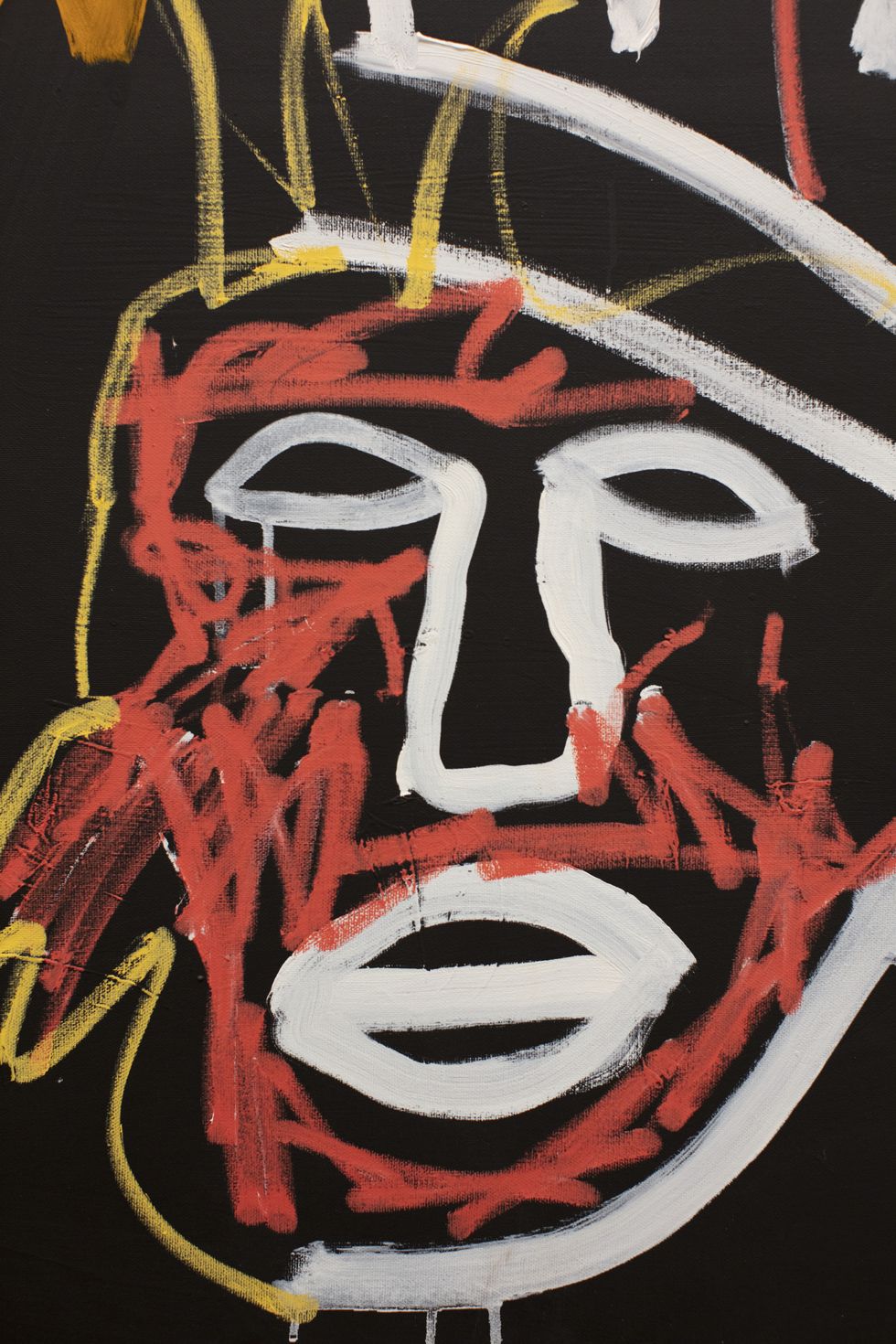

A series of details from Untitled (Cowboy and Indian).

In the brief span of his artful life, Basquiat was incredibly prolific. It is estimated that he left behind nearly 2,000 completed works at the time of his death. By then, he was already an established presence in the booming art market of the 1980s, having created a corpus of paintings, drawings, and other works that drew upon influences like jazz and history and bridged two dominant aesthetic movements of the era, neo-expressionism and hip-hop.

These days, if you want to see a Basquiat, you don’t have to look very far. His crowns, skeletal figures, masked faces, and text fragments now seem to be almost everywhere—emblazoned on T-shirts, hats, jackets, scented candles, skateboards, sofa throws, Dr. Martens, and Converse sneakers. (I’ve even purchased Basquiat face masks for my kindergartner.) Just last fall, Tiffany & Co. unveiled an ad campaign with Beyoncé, Jay-Z, a 128-carat diamond, and Basquiat’s rarely seen 1982 painting Equals Pi, which prominently features a robin’s-egg blue.

Up until recently, Lisane and Jeanine have focused primarily on brand management of the Basquiat estate, an occupation they took up after the death of their father, Gerard Basquiat, in 2013; he had served as its previous administrator. Both women have extensive business backgrounds: In addition to overseeing the estate, Lisane, who was a corporate executive, is also a life strategist and entrepreneur; Jeanine has worked in finance.

To the sisters, the broad availability of Jean-Michel’s work comports with his own approach to making art, which he created on every surface he had access to, from walls, tabletops, and napkins to leather jackets, unhinged doors, and disused window frames.

“We own the copyright to all works,” Jeanine says. “And from our standpoint, the licensing has really allowed the public to see his works that they might not have otherwise seen because they might not have access to a museum or might not be familiar with them.” Lisane, nodding, concurs. “People can access Jean-Michel’s works through images that are on different materials,” she says. “That is also a way that his legacy continues.”

Despite the apparent ubiquity of Basquiat’s work, interest in it remains at an all-time high. In 2018, a career-spanning retrospective filled four floors of the Frank Gehry–designed Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. The following year, there were the back-to-back exhibitions “Jean-Michel Basquiat” at the Brant Foundation and “Basquiat’s Defacement: The Untold Story” at the Guggenheim in New York. “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” opened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2020, and “Warhol and Basquiat in Focus: Works From the Permanent Collection” was at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh this past summer.

Even the most prominent collectors of his art are feeling the pressure to share it with the public. After purchasing Basquiat’s 1982 Untitled in 2017 for a record-breaking $110.5 million—the highest sum ever paid at auction for a work by an American artist—Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa pledged to ensure the painting would be exhibited. He did so in 2018, lending it for the “One Basquiat” exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, the site of a Basquiat retrospective in 2005 and a place young Jean-Michel frequented as a child with his mother. Maezawa also announced plans to open a museum based on his collection in his hometown of Chiba.

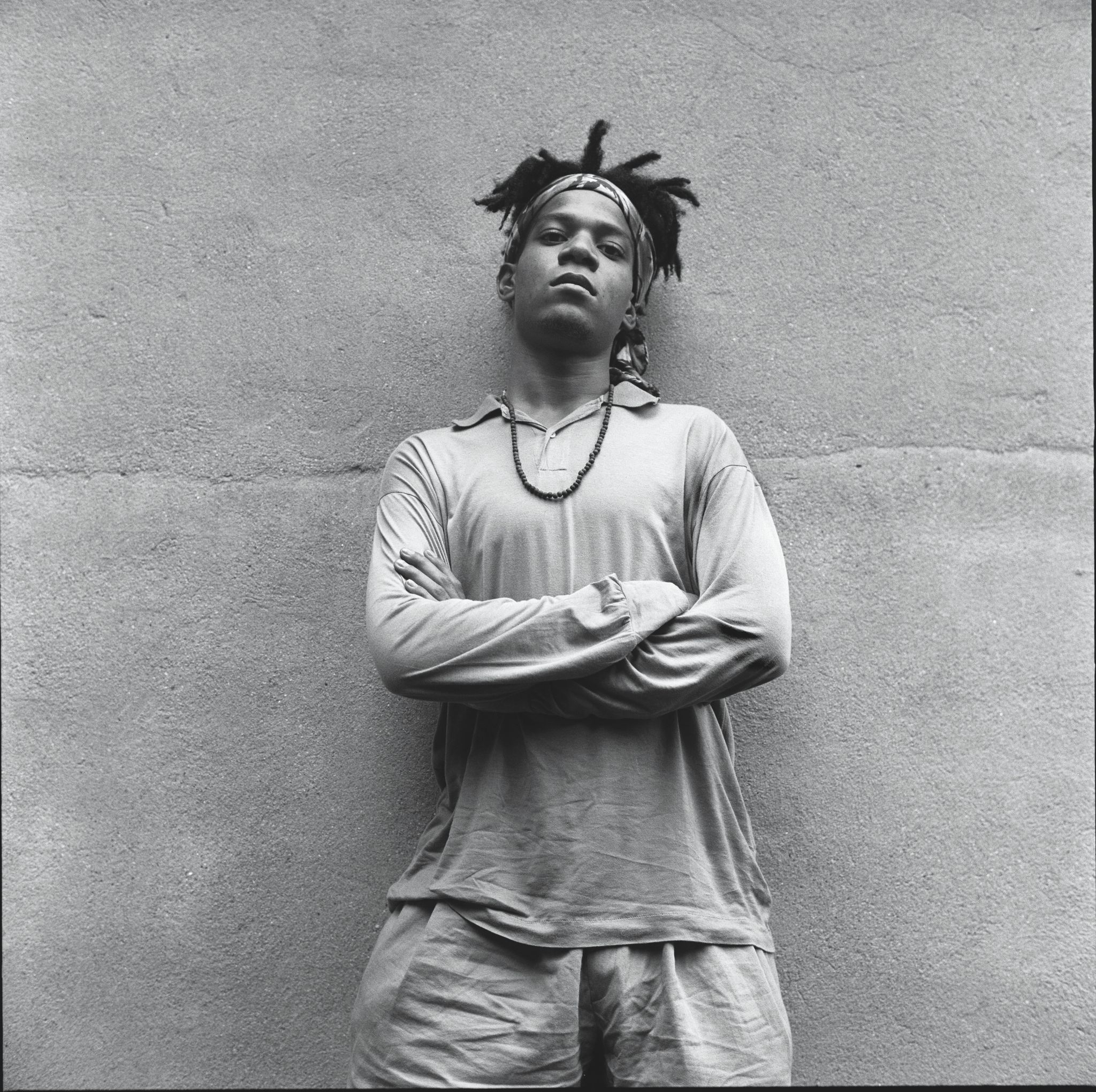

The story of Basquiat’s ascent typically goes something like this: Born in 1960 to Matilde Andrades, who was of Puerto Rican descent, and Gerard Basquiat, an accountant from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Jean-Michel spent his early years in Brooklyn. When he was eight, his parents separated. He and his siblings at first lived with Matilde, who had moved back in with her parents, before she and Gerard decided together that it would be best for them to live with him in order to maintain the stability and lifestyle they’d known before the split. Gerard and the kids moved to a townhouse in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, then relocated to Puerto Rico for a period before coming back to New York. Jean-Michel left home at 17 and began sleeping on park benches and living with a succession of girlfriends (including, for a brief period, a pre-fame Madonna). With his high school friend Al Diaz, he began to spray graffiti art throughout downtown Manhattan with the tag SAMO©. By the time he was 20, he’d started a post-punk band, Gray, with filmmaker Michael Holman and actor Vincent Gallo and starred as a fictionalized version of himself in the indie film Downtown 81. He had also begun painting postcards, which he sold on the street, eventually turning to canvases. Fast-forward four years and he was one of the biggest art stars of the ’80s, opening a show with Warhol, who had taken him under his wing (some said opportunistically), before Warhol’s death in 1987 and Basquiat’s own excesses consumed him.

But at his peak, Basquiat was still an outlier. Even though he achieved a level of fame and fortune unknown to any Black artist before him, he felt rejected by critics and cultural institutions alike. The New York Times review of “Basquiat, Warhol” referred to him as an “art world mascot,” and his work was regularly fetishized as “primitive” and “exotic.”

Early attempts to memorialize him after his death served to reinforce other pathological readings. Julian Schnabel’s 1996 film, Basquiat, starring Jeffrey Wright, opens with Basquiat waking up in a cardboard box in Tompkins Square Park and depicts him as brilliant but also volatile, indigent, and entirely denying his own middle-class upbringing. Phoebe Hoban’s unauthorized 1998 biography, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, painted a stark and at times unsettling portrait of Basquiat’s childhood, rise to fame, and descent into addiction.

During his life, Basquiat himself could be cryptic and evasive when it came to his past. When I ask the sisters how they feel about the way their family has been portrayed in or even left out of some of the more dominant accounts, Jeanine responds candidly: “It’s less about what’s not said. It’s more about what is said,” she explains. “What I have heard was that Jean-Michel left home and he was adopted by a white family. Or lived in a box. Or never saw his family again. Or that Jean-Michel’s mother was locked away in an institution for 30 years. These are things that are factually incorrect. So it’s more about correcting things than being included in the story.”

However, Basquiat did put his experience of racism and everyday vulnerability as a young Black man in America front and center in his work. He was deeply affected by the death of Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old Black graffiti artist who fell into a coma after he was forcibly restrained and hog-tied by police following his arrest in a New York City subway station. (Stewart died 13 days later.) It inspired his 1983 piece The Death of Michael Stewart (also known as Defacement), which he created on the wall of Keith Haring’s studio. (Haring subsequently had it excavated and framed.)

“Jean-Michel’s Blackness was always called into question by peers, by critics, by the art world, by him just going through life day to day, and so that was a constant,” Jeanine says. “You could tell how important it was to him by the way he constantly referred to it in his work. He had been dealing with it from a very young age. All those little microaggressions that most Black people experience weighed heavily on him.” As cultural critic Greg Tate, who co- curated the “Writing the Future” exhibition at the MFA, Boston, observed in 2020, Basquiat repeatedly ruminated on Black artists and athletes in his work. “The high regard he had for jazz musicians is immediately apparent,” Tate wrote. “Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, and other bebop kings totemically recur as ready-made titans of Black male genius—men the fame-, reward-, and respect-obsessed Basquiat knew were revered worldwide for their creative prowess, cosmopolitan style, and street cred.”

Tate, who passed away in December, was also one of the first writers to explore Basquiat’s links to hip-hop. Tate offered a landmark exploration of the subject in a 1989 essay for The Village Voice, “Nobody Loves a Genius Child: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lonesome Flyboy in the ’80s Art Boom Buttermilk.” (The title is cribbed from a Langston Hughes poem.) Contemporary artists like Jay-Z and Swizz Beatz, who both collect Basquiat’s work, have extended this lineage. (“I’m the new Jean- Michel,” the former famously declared on his 2013 song “Picasso Baby.”)

Fortunately, there have been more recent attempts to shed light on Basquiat’s diverse Black cultural heritage and how he inspired his contemporaries and a new generation of Black artists who came of age after his death. Children’s book author Javaka Steptoe won both the Caldecott Medal and Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award in 2017 for his thoughtful portrait of Basquiat’s early years in Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Art historian Jordana Moore Saggese’s 2014 book Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American Art is a scholarly examination of how Basquiat engaged his various identities, the creation of his work, and its complicated reception in the white art world, while Nigerian American filmmaker Julius Onah recently announced that he is making SAMO Lives, a new biopic celebrating Basquiat’s life and African diasporic legacy.

Basquiat seldom spoke about his childhood in any depth in interviews. But he did credit his mother for nurturing his interest in art. When he began drawing at the age of three, often on paper that his father brought home from work, Matilde would sketch alongside him. She took him frequently on trips to the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum, to which Jean-Michel, at six, had his own junior membership. It was also his mother who introduced him to the medical textbook Gray’s Anatomy, which she gave him when he was eight and hospitalized after being struck by a car while playing in the street. Throughout his life, he constantly returned to it as source material, naming his band after it and using it in 1982 as inspiration for his first portfolio of prints, titled “Anatomy.” Jean-Michel was not only a multilingual adolescent, fluent in English, French, and Spanish, he also grew up surrounded by his father’s extensive record collection, heavy on jazz and bebop. “King Pleasure©” doesn’t avoid the more difficult parts of Jean-Michel’s life. But it does delve into the deep and complex nature of his relationship with his family and how the sense of identity that his parents tried to build for their children helped shape him.

“This exercise of curating the show gave me a new perspective on how we were each impacted by having him leave when he did,” Lisane says. “We were three siblings, and one of the siblings is gone. This was my brother, and his life was stopped short, and in an instant. And when that happens, there’s a freeze-frame for everybody. “He was incredibly protective,” she adds. “He was funny as hell. He was mischievous. He was like this master wizard, always coming up with one scheme after another and recruiting Jeanine and I into the shenanigans. He was also figuring out who he was and what he wanted to do and how he wanted to show up.”

For Adjaye, “King Pleasure©” is about both recontextualizing Basquiat’s genius and also uncomplicating it. “What was very important to me is for a young Black kid who is looking at this and thinking about being an artist to be able to see themselves in it,” Adjaye says. “So the story is made to unfold in a way that’s relatable now, not exceptional. Even though he’s exceptional in that he’s a moment in history at that time, he’s not exceptional in the sense of what Black families were doing for their children and trying to support them at that time.

“All great artists write their narrative,” Adjaye adds. “He was writing his own.”

“I would encourage anyone to think about themselves in their early 20s, hanging out with their friends, and to imagine if someone were to take that sliver of your life and say, ‘Let me tell you the story of this person,’ ” Lisane says. “So it’s not that it was wrong, but what this show will do is provide a view of Jean-Michel within the broader context of his life,” she explains. “Jean-Michel was always determined as hell to do what he wanted to do with his life, and that’s what he did.”

Years later, it seemed that Basquiat had internalized it all as a source of strength. “Since I was 17, I thought I might be a star,” he said. “Even when I didn’t think my stuff was that good, I’d have faith.”

Hair: Tashana Miles at The Chair for The Chair Beauty; Makeup: Jessica Taylor.