What does it mean to reject or accept the histories attached to a landscape? Scholars and activists have worked diligently to build a damning history of Argentina’s most recent military dictatorship, primarily through the collected memories of survivors. These accounts have created a lasting body of evidence attesting to the regime’s depravity and recognizing the 30,000 lives lost in the fight against “subversion.” However, the landscape of Buenos Aires contains other memories of this recent history that are not so readily recognized yet reveal a more complicated legacy of the military’s push to transform the nation and its people.

The Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur in Buenos Aires was born in the violent destruction of this time period but is more often associated with life. Located on the southern coast of the urban core of Buenos Aires, the Reserva covers approximately 860 acres (349 hectares) and serves as both a protected space for local wildlife and a public park. Dirt paths wind throughout it, allowing runners, walkers, and cyclists to traverse the marshlands and find their way to the shores of the Río de la Plata. Visitors can also use exercise equipment along the paths, have picnics at the river’s edge, or just enjoy the relative quiet compared to the bustling city a stone’s throw away. Employees offer educational programs for children and nature enthusiasts who want to learn about the flora and fauna found within the Reserva. Lookout points (miradores) bear the names of various Argentine naturalists and environmentalists with accompanying signage documenting their accomplishments. The Reserva’s overall structure and activities promote appreciation for the local ecology.

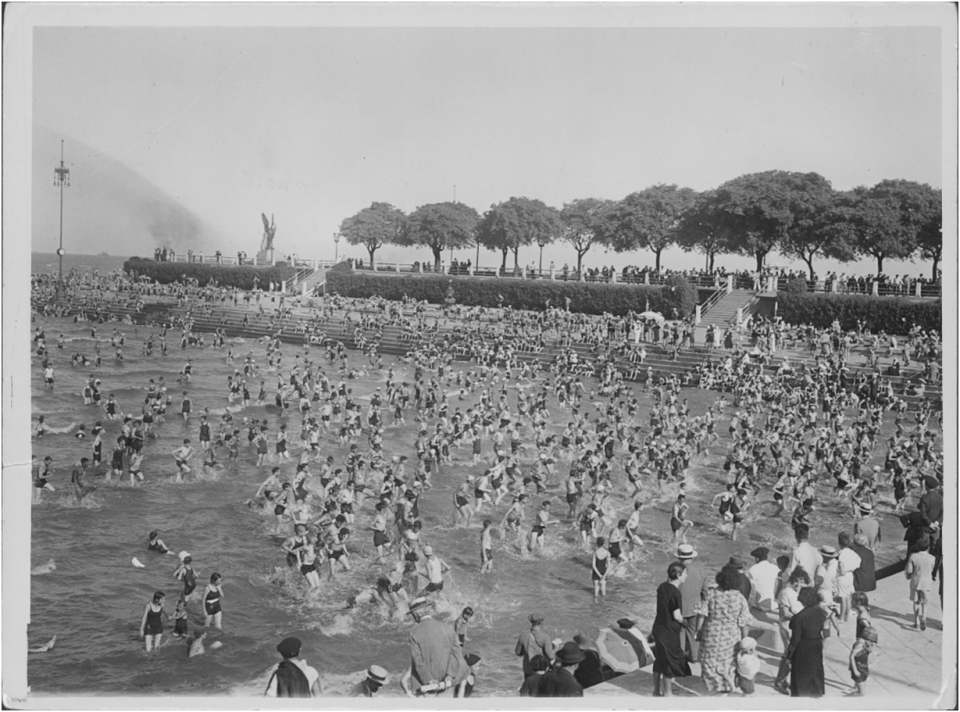

Closer examination of the park raises questions, some of which have readily available answers while others do not. To the right of the entry path, a long concrete and marble structure stretches towards the river. Signs outside of the Reserva’s entrance note that in the first half of the twentieth century, this was the site of the Balneario Municipal or the public swimming area. Opened to the public in 1918, this breakwater originally jutted out into the Río de la Plata, and steps leading down into the water gave Porteños—the name for citizens of Buenos Aires—a welcome respite from intense summer heat. Avenida Costanera Sur, which now goes by the name Avenida Dr. Tristán Achával Rodriguez, ran parallel to the water’s edge and was lined with restaurants and cafes. Throughout much of the twentieth century, since the construction of this space in 1918, Porteños cherished that contact with the river and the social interaction the space provided.

However, the signage in and around the Reserva offers no explanation as to how land came to surround the breakwater, cutting it and the Avenida off from the river. The Reserva’s website brushes over this critical development; it simply notes that the local government (no specific names attached) dumped “rubbish” into the shallows starting in 1978 under the pretense of constructing a municipal administrative center, though the project never came to fruition.

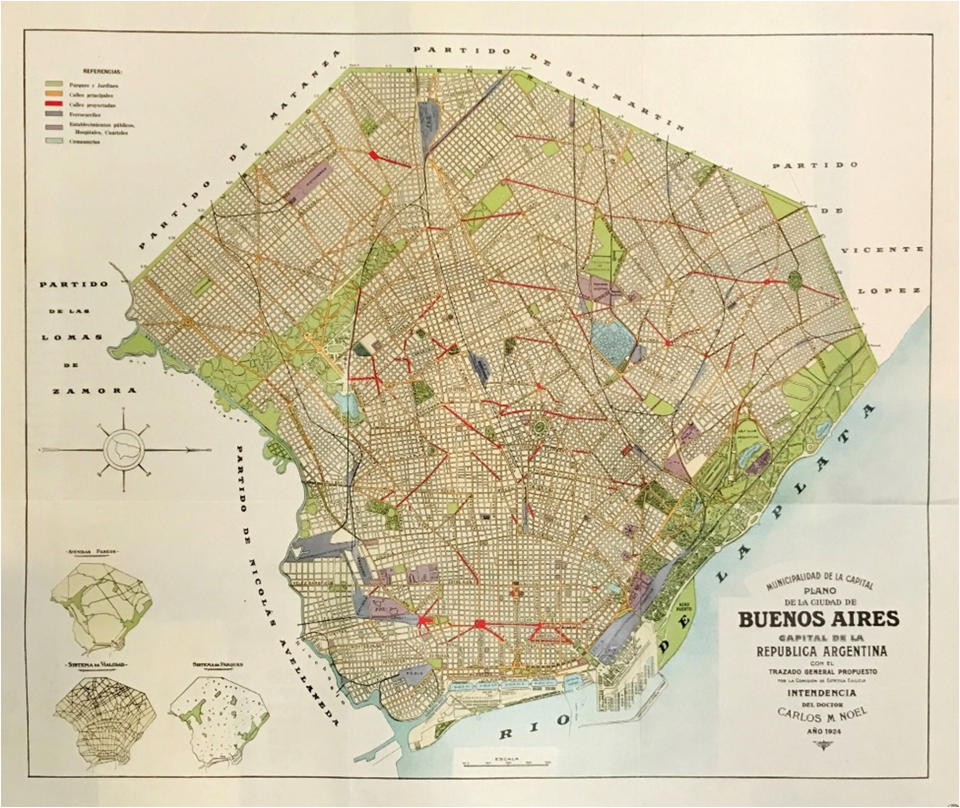

The 1925 master plan for Buenos Aires.

The 1925 master plan for Buenos Aires.

Image originally published in Comisión de Estética Edilicia. Proyecto orgánico para la urbanización del municipio, El plano regulador y de reforma de la Capital Federal. Buenos Aires: Talleres Peuser, 1925.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

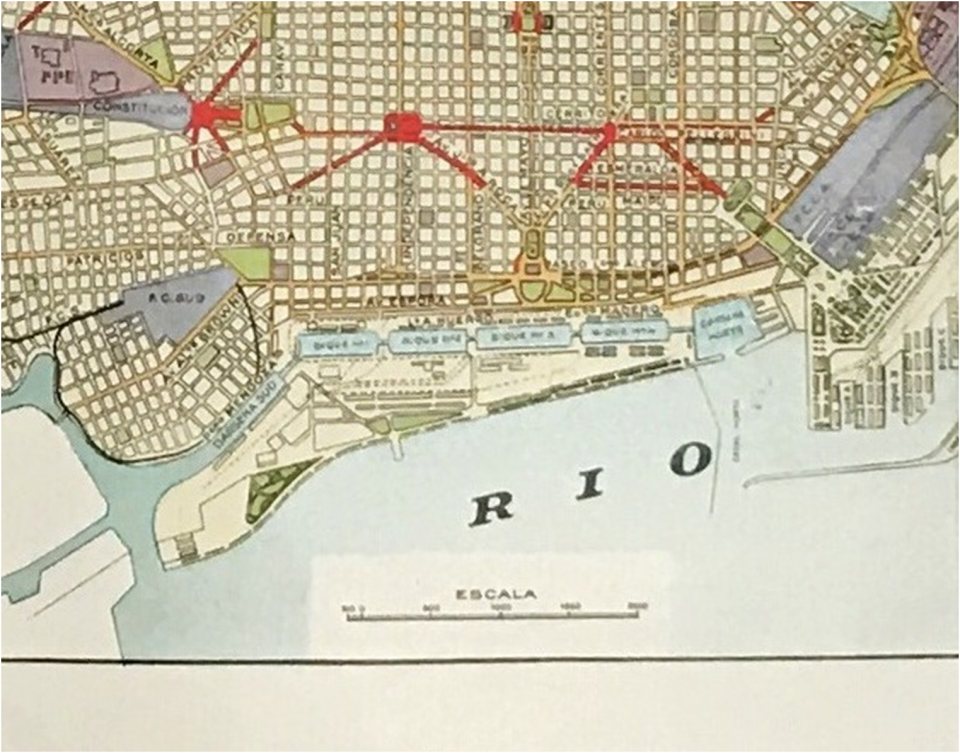

A close-up of the Costanera Sur from the master-plan map. Note the breakwater jutting out into the river and how the original avenue is situated immediately next to the river.

A close-up of the Costanera Sur from the master-plan map. Note the breakwater jutting out into the river and how the original avenue is situated immediately next to the river.

Image originally published in Comisión de Estética Edilicia. Proyecto orgánico para la urbanización del municipio, El plano regulador y de reforma de la Capital Federal. Buenos Aires: Talleres Peuser, 1925.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Closer examination of this period shows how the military dictatorship simultaneously pursued an ambitious set of urban reforms meant to create a more efficient and modern Buenos Aires. This agenda included building several highways within the dense city and as construction began on the first highway, Autopista 25 de Mayo, in 1977, thousands of properties were demolished to clear a path for the highway. Military mayor Brigadier (RE) Osvaldo Cacciatore ordered that the rubble be deposited in the coastal shallows as part of a larger effort to “reconquer the river” and create a new neighborhood along the littoral. The mayor earmarked the land built up through this reconquest for both municipal offices and private development. The only thing that kept this vision from becoming a reality was the regime’s own waning power, which put an end to such schemes by 1983. Today, a small, haphazard display in the Reserva’s visitor’s center notes these origins, and debris found embedded in paths and at the water’s edge make clear the park’s origins.

Two present-day views of the Reserva’s shore where concrete and rebar (left), along with bricks and mortar (right), attest to the origin of the park (June 2014 and July 2008, respectively).

The limited recognition of the park’s origins under the dictatorship reveals a desire to build a different narrative. The Reserva’s website tells of how local plant and animal species rewilded the area in the 1980s, setting the stage for this landscape’s new life. A plaque at the entrance celebrates the fifteenth anniversary of the Reserva’s formal establishment on 5 June 1986, which also happens to be Earth Day. Coupled with signage, miradores, and urbanites desiring contact with nature, Porteños have reclaimed the landscape that had been taken by the military. In doing so, the Reserva moves past memories of violence by becoming a space dedicated to preserving life rather than to a regime that destroyed life.

How to cite

Hoyt, Jennifer. “Memory and the Origins of the Reserva Ecológica Costanera Sur in Buenos Aires.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2019), no. 13. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8611

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2019 Jennifer Hoyt

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Brennan, James P. Argentina’s Missing Bones: Revisiting the History of the Dirty War. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

- Davis, Brian. “Reserva Ecológica: Three Streams of Material Excess in Buenos Aires.” In 101st ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings: New Constellations, New Ecologies, edited by Ila Berman and Edward Mitchell, 29–36. Washington, DC: ACSA Press, 2013.

- Gutman, Margarita, and Jorge Enrique Hardoy. Buenos Aires, 1536–2006: historia urbana del Área Metropolitana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Infinito, 2007.

- Hoyt, Jennifer T. “Clean, Fast, and Green: Urban Reforms in Buenos Aires and Cold War Ideologies, 1976–1983.” Urban History 42, no. 4, special issue on Cold War cities (November 2015): 646–662.

- Martire, Agustina. “Waterfront Retrieved: Buenos Aires’ Contrasting Leisure Experience.” In Enhancing the City: New Perspectives for Tourism and Leisure, edited by Giovanni Maciocco and Silvia Serreli, 245–74. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009.

- Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.