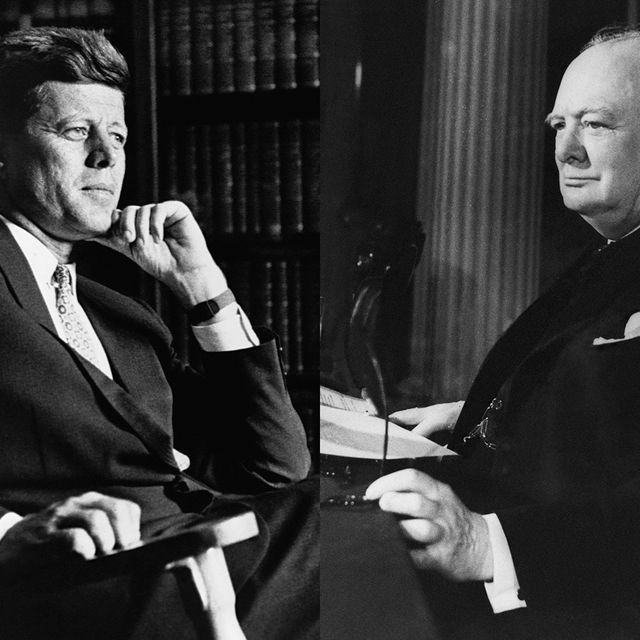

Winston Churchill was the second son of a prominent British aristocrat. John F. Kennedy was the second son of a striving, Irish Catholic, Boston businessman. Although the two men were from different generations, born more than 40 years apart, these iconic leaders shared a mutual passion for politics, history and the written word, and in Churchill, a young Kennedy found a lifelong idol, who helped shape the worldview of America’s 35th president.

Churchill helped inspire Kennedy’s love of history

Illness plagued Kennedy for much of his life. As a child and young adult, frequent hospitalizations for a variety of ailments left him with a sense of loneliness and isolation. An avid reader, he turned to books to fill his time. He read widely throughout his life, admiring everything from Ernest Hemingway’s fiction and Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, to Pilgrim’s Way, a World War I-era memoir by British aristocrat John Buchan (he later gave future wife Jacqueline Bouvier a copy of Buchan’s book while they were dating).

Kennedy developed a passion for history and biography, and the work of Churchill in particular. Although perhaps better known today for his political career, Churchill was also an accomplished journalist, essayist and historian. One of his earliest successes was The World Crisis, a six-part chronicle of World War I published between 1923 and 1931. Three years after the final volume was published, a friend of JFK’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., wrote of his surprise at seeing 16-year-old John reading Churchill’s opus while recuperating at the Mayo Clinic. Nearly two decades later, when Life magazine asked now-President Kennedy to name his favorite books, Churchill again made the list, with JFK citing his massive biography of ancestor John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough.

READ MORE: 12 Notable Members of the Kennedy Family

Kennedy admired Churchill despite his father’s feud with the British politician

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Joe United States Ambassador to the Court of St. James, America’s top diplomatic post in the United Kingdom. Most of Kennedy’s family joined him in London, including John, who temporarily postponed his education at Harvard University to work in his father’s office and travel throughout Europe gathering research for his senior thesis.

The Kennedys arrived at a time of uncertainty and crisis. Adolf Hitler’s rearming of Germany and expansionist foreign policy left many in the UK divided over how best to handle the growing Nazi threat. A committed isolationist, Ambassador Kennedy supported the more conciliatory approach of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who negotiated the Munich Agreement with Hitler, meant to prevent an outbreak of war, the same year Joe and his family arrived in London.

This brought Kennedy into sharp conflict with Churchill and his supporters, fierce critics of Chamberlain’s “appeasement” policies and advocates of a more aggressive approach to Hitler. After war broke out in August 1939, Ambassador Kennedy became even more pessimistic, and after giving a series of newspaper interviews criticizing American aid to the UK and questioning Britain’s ability to survive a possible Nazi onslaught, the ambassador found himself in Churchill’s crosshairs. Shortly after becoming Prime Minister in May 1940, Churchill helped convince President Roosevelt to recall Joe to the United States, ending his brief diplomatic career.

Just months later, Joe helped find a publisher for an expanded version of John’s Harvard thesis, which took a more nuanced look at pre-WWII British foreign policy — and partially rejected his father’s isolationist views. The impressionable John even paid homage to Churchill with the book’s title, calling it Why England Slept, a tip-of-the-hat to While England Slept, Churchill’s 1938 collection of his own speeches during the inter-war years.

READ MORE: Inside John F. Kennedy and Frank Sinatra's Powerful Friendship

The Kennedy-Churchill connection remained fraught during JFK’s early career

Despite his father’s early opposition to the war (and his own precarious health), John was eager to serve. But the war took its toll on the family. Eldest son Joe Jr. was killed while serving in Europe and John nearly lost his life when his PT-Boat was sunk in the Pacific. Faced with the pressure to assume his father’s political ambition for his now-dead eldest son, John launched his first campaign, for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1946.

While he initially spoke of his admiration for Churchill’s leadership role during the war, he soon realized that his Boston constituents, many of them Irish Catholic immigrants or the descendants of recent immigrants, were perhaps not as fond of a British upper class whom they believed had persecuted them. John toned down the pro-British talk — and won the election.

JFK’s beloved sister Kathleen, known as Kick, remained in Britain during the war, marrying a Protestant British aristocrat against her mother’s wishes. When he was killed at the front just months after their marriage, a grieving Kick became close friends with Churchill’s daughter-in-law, Pamela. Despite his ongoing dislike of her father, Churchill was also charmed by Kick. He and his family vacationed near the Kennedy compound in Florida, and when Kick died in an airplane crash in 1948, Churchill’s message of condolences helped briefly thaw the tensions between the two men.

READ MORE: Did the Mob Kill John F. Kennedy?

JFK didn’t actually meet Churchill until the 1950s

John had been enthralled by his idol since his youth and had listened to several of his speeches in the Houses of Parliament during the early days of World War II, but it wasn’t until he was a U.S. Senator and on the verge of running for the presidency that he and Churchill were finally introduced.

According to oral histories in the Kennedy Library, their first encounter was rather inauspicious. John and his wife were vacationing with British friends in the South of France in 1958 when they received an invitation to join a dinner aboard a yacht owned by Greek tycoon Aristotle Onassis (who would later marry Jacqueline Kennedy after JFK’s death). Churchill was a guest of Onassis’ and had asked to meet the promising young American politician. But by now in his 80s, Churchill was no longer as sharp-minded as he’d once been, and the two men spoke only briefly, mostly about John’s political ambitions. Churchill’s low-key reaction to meeting John seemed to surprise everyone, leading Jackie to quip that perhaps Churchill had mistaken the boyish JFK who had dressed in a white dinner jacket for the occasion, reportedly saying, “I think he thought you were the waiter.”

READ MORE: Why Robert Frost Didn't Get to Read the Poem He Wrote for John F. Kennedy's Inauguration

JFK helped grant Churchill one of America’s greatest honors

A writer and master orator himself, John frequently quoted and spoke of Churchill throughout his 1960 presidential campaign. He invited Churchill to visit Washington, D.C. following after his election, but Churchill was too frail to travel.

In April 1963, with John’s urging (and just seven months before his own assassination), the U.S. Congress passed legislation making Churchill, whose mother had been born in the United States, an honorary American citizen. Churchill was the first to receive the honor, and one of only eight to be so honored. Churchill was again too frail to travel. His son, Randolph, accepted on his behalf, but Churchill watched a satellite transmission of the ceremony from the White House Rose Garden, as John proclaimed, “We meet to honor a man whose honor requires no meeting — for he is the most honored and honorable man to walk the stage of human history in the time in which we live… By adding his name to our rolls, we mean to honor him — but his acceptance honors us far more. For no statement or proclamation can enrich his name — the name Sir Winston Churchill is already legend.”