Salomé Gómez-Upegui is a Colombian-American writer and creative consultant based in Miami. She writes about art, gender, social justice, and climate change for a wide range of publications, and is the author of the book Feminista Por Accidente (2021).

German-born Venezuelan artist Gertrud Goldschmidt, better known as Gego, spent her decades-long career exploring the infinite potential of the line. Her creations, which range from delicate drawings to hanging sculptures and environmental installations, often crafted using metal, hypnotize viewers as their lines are twisted, turned, pulled, and pushed into unexpected dimensions.

Gego’s uncanny ability to alchemize simple forms into extraordinary arrangements led many critics to consider her one of the most important Latin American artists of the twentieth century. And yet, the breadth of her genius has seldom received the attention it deserves.

Born in Hamburg, Germany in 1912, Gego permanently relocated to Venezuela when she was twenty-seven years old, settling in Caracas. It was the onset of World War II, and while most of her family was able to escape to England, sailing for the South American country was her way of fleeing Nazi persecution.

Just a year before, Gego, who was from an affluent Jewish family, had graduated with a degree in architecture and engineering from the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart—known today as Universität Stuttgart. Despite not knowing anything about Venezuelan culture, let alone the language, she diligently built a life for herself and continued her career in architecture, working as a freelancer for various local firms over the next decade.

[GEgo] was a very inspiring figure in the language of abstraction in Venezuela. . . . She was able to toe the line between who she wanted to be and who she really was.

Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães

By the 1950s, Gego was married with two children and now an official citizen of Venezuela. Yet, never one to follow a predictable path, this was the start of a momentous period in her life, marked by drastic change.

At the start of the decade, she separated from her first husband, German businessman Ernst Gunz, and met the man she would spend the rest of her life with, Lithuanian-born artist Gerd Leufert. In 1953, alongside Leufert, she moved to Tarma, Venezuela, a minuscule mountain village. Here, for the first time, she devoted herself entirely to artistic production. And although she abandoned engineering and architecture for good, her professional roots would continue to reverberate throughout her artistic career.

Although Gego was in her early forties when her path as an artist officially began, and architecture is sometimes regarded as her first passion, she always had a unique sensibility for art. “My interest in, and dedication to, the visual arts developed quite early and was stimulated from the very beginning. My inclination toward architecture came later,” she wrote in one of her journals.1

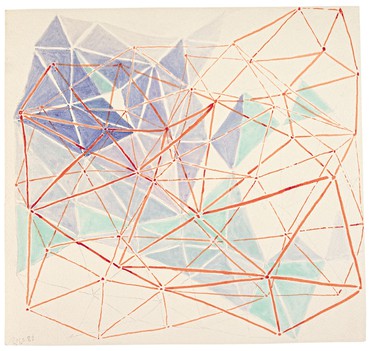

The first works she produced in Tarma were mostly drawings, watercolors, and engravings that explored common themes such as figuration, landscape, and architectural sites. But by 1956, she had moved back to Caracas, and with the encouragement of renowned Venezuelan artists Alejandro Otero and Jesús Rafael Soto, she began to forego works on paper and explore three-dimensional compositions instead. From then on, her artistic style quickly evolved toward the mesmerizing creations for which she would become known.

One of Gego’s most transgressive and well-known works is her enthralling Reticulárea (1969–82). With a title that alludes to a web of nets, this enormous, three-dimensional constellation of squares, triangles, and other shapes is constructed from stainless steel and aluminum, and hangs from the walls and ceiling. The first iteration of this bewitching environment was installed in 1969 at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas, and subsequently at different sites around the world, where it was meticulously reconfigured according to each particular space.

Like that of many Latin American women artists of her time, Gego’s oeuvre has been consistently underrated and undervalued outside the region—especially in the United States. Aside from Questioning the Line: Gego, A Selection, 1955–90, a posthumous retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 2002, there have not been proper institutional efforts in North America to understand the magnitude of her contribution—until now.

Gego: Measuring Infinity at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (March 31–September 10, 2023) is a unique presentation of the artist’s expansive oeuvre. Cocurated by Pablo León de la Barra and Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães, the exhibition features Gego’s work across five ramps of the museum’s rotunda, with around two hundred pieces from the artist’s prolific career, including sculptures, drawings, textiles, installations, and publications.

“She was a very inspiring figure in the language of abstraction in Venezuela—very distinct from her peers. . . . She was able to toe the line between who she wanted to be and who she really was. She defied labels and never wanted to be placed in a certain category. She never wanted to be known as a geometric abstract artist or a kinetic artist,” says Gutiérrez-Guimarães.2 Indeed, while distinguished peers such as Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez were delving deeper into kinetic art and geometric abstraction, Gego was busy pushing the boundaries of these forms.

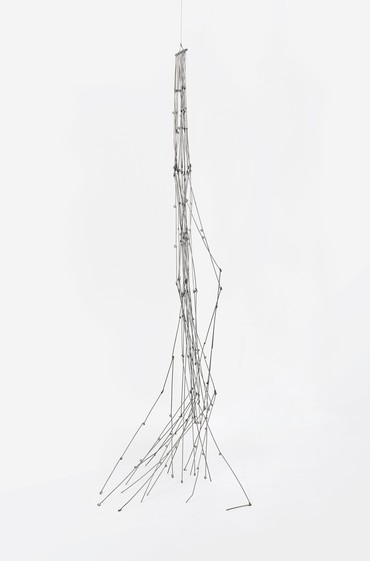

In works such as Sphere (1959), a globe-like structure made from black-painted steel rods, she experimented with the idea of movement and illusion, by creating a piece that was actually static but appeared to move with the gaze of the viewer. Similarly, in her acclaimed Chorros (Streams) (1970–74), a series of disorderly vertical figures reminiscent of water fountains, made from metal rods that cascade from the ceiling and collide with the floor, she distanced herself from the stringency of geometric abstraction.

“She was mostly known as a sculptress and a draftsperson. In the show, we’re really highlighting her steel, aluminum, and bronze sculptures as well as drawings and prints. She was an excellent printmaker, and few people know that she also worked with textiles, and was an educator for over twenty years in Caracas,” Gutiérrez-Guimarães adds.3

Though many of Gego’s works are commonly considered sculptures, she adamantly opposed this description herself, famously writing in a journal: “Sculpture, three-dimensional forms of solid material. Never what I make.”4 Instead, she was interested in playing with subtle traces, volume, and transparency.

Gego’s love of these elements is wonderfully evidenced in her longest-running series, Dibujos sin papel (Drawings without paper) (1976–88), for which she laboriously developed structures made from small pieces of hardware, metal scraps, and wires, installed close to the wall, floating, almost giving the impression of being drawn directly onto the surface.

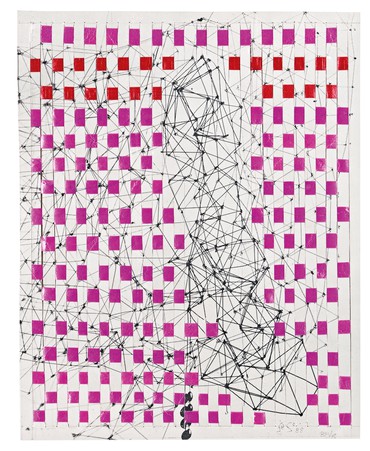

Even toward the end of her life, Gego continued to innovate and produce surprising works. For Tejeduras (Weavings) (1988–91), her last series, she wove strips of paper sourced from magazines, cigarette packaging, commercial leaflets, and even some of her own works on paper to create grid-like compositions that once again drew on the unexpected to explore the infinite possibilities of the humble line.

Gertrud Goldschmidt passed away in Caracas in 1994 at the age of 82. She lived a life of playfulness and inventiveness, and despite her fixation with lines, geometric shapes, and boxes, she refused to exist within their confines. As she herself wrote: “there is no danger for me to get stuck, because with each line I draw, hundreds more wait to be drawn.”5

1María Elena Huizi and Josefina Manrique, eds., Sabiduras and Other Texts by Gego (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2005), p. 235.

2Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães, Zoom conversation with the author, March 3, 2023.

3Ibid.

4“July 2014. Gego in Leeds. Three-Dimensional and Transparent.” Fundación Gego. Available online at https://fundaciongego.com/en/july-2014-gego-in-leeds-three-dimensional-and-transparent/.

5Gego, “Testimony 4,” in Sabiduras, p. 170.