Art

Rethinking Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp: La Peinture, Meme, the current exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, is a refreshing new look at Duchamp with many surprises. The title is fittingly a double entendre. Translated, it means “Even Painting” but the words spoken in French can also mean “Painting Loves Me.” The show is meticulously researched and brilliantly installed by Beaubourg curator Cécile Debray. The thematic spaces contain not only Duchamp’s paintings, but also works related to their context and conception. It is as close to a complete Duchamp painting retrospective as possible, missing only his dramatic farewell to the medium, the 1918 “Tu m’.”

The enigmatic unfinished title “Tu m’” has been interpreted in several ways but “tu m’ennuie”—you bore me—seems the most accurate completion of the title. The truth is painting did bore Duchamp; his philosophical mind wanted more than images, surfaces, and colors from art. He wanted ideas and ways to play with them. The show follows his search for an alternative to what he disparagingly termed “retinal art” which appealed only to the eye but not to the mind.

Planting Duchamp firmly within his own contemporary culture and personal experience, the exhibition gives a much better picture of his ambitions and frustrations and the unity of his thought and accomplishments. This reading of his origins, sources, pursuits, and passions permits a glimpse of the secretive, vulnerable artist behind the carefully constructed mask of punster, trickster, transgressor, and distant cold strategist he fashioned to protect himself from those who would understand or misunderstand him too quickly. For all the endless number of Duchamp exhibitions, critical and academic exegeses, this has never adequately been done before.

The show is large, ambitious, and provocative. It opens with an introductory gallery containing the puzzle-like linear engravings Duchamp made at the end of his life based on images taken from Courbet and Rodin. It includes puppets popular when he was a child, the Boîte-en-valise containing the mini reproductions of his works, his first “sculpture,” a charming racetrack with handmade toy horses, and the “original” 1919 small faded reproduction of Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa” on which Duchamp drew a mustache, goatee, and the letters LHOOQ, a dirty joke in French.

The reproduction Duchamp altered was made for the 400th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, whose role as artist and scientist, inventor and innovator was obviously the one Duchamp would have liked to emulate. But it was too late. Art and science had branched off into two separate specialized disciplines that could no longer be reconciled. As for artistic innovation versus scientific invention, Duchamp realized early on that only science but not art could alter the world. Defacing a reproduction of a work by Leonardo was his best effort to change history, even if it was only a gesture reflecting the inevitable disappointment of his own ambitions.

The country fair puppets, toys, and miniatures evoke the childhood of the artist who was born in Blainville-Crevon, a small farming village in Normandy outside Rouen where his father was the notary and mayor. Games were extremely important to family life in the country. As a child, Marcel was especially close to his sister Suzanne, his willing playmate in activities conjured up by his fertile imagination. While the parents stayed home in the country, their gifted children were sent off to Rouen to study at the best lycée. His older brothers Gaston and Raymond, who became famous as painter Jacques Villon and sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, who left the family patronym to their younger sibling, were already there when 8-year-old Marcel joined them. At the lycée, he showed an aptitude for mathematics and won a prize for drawing. His first serious art attempts were drawings and watercolors he made at age 14 depicting his sister in various poses and activities.

The next section contains projections of a number of “racy” early silent movies of brides removing the layers of wedding finery in the presence of a voyeuristic husband or lover. The most amusing is the transvestite striptease in which the bride, once naked, turns out to be a man in drag. It is unforgettably and hysterically funny. To understand Duchamp’s gender bending, one has to see it in the context of his own time when, as Cole Porter wrote, “a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking.” Today, anything goes. But we should remember Duchamp, born in 1887, grew up in a provincial world of puritanical inhibitions. We have snuff movies, sex toys, and every conceivable form of Internet porn available on demand. Not sex outside of marriage, but the right to have government health insurance pay for transsexual operations is the cutting-edge issue.

In Duchamp’s day, cutting edge was collections of erotic photographs (basically well-endowed naked ladies demurely posed in interiors or landscapes) that could be viewed in relative privacy through a stereoscope, a device for fusing two separate images into one apparently three-dimensional image by looking through two apertures, each with a different lens focus, which made the image appear larger and more distant. Examples of these peep show machines and early photographs are also included in the show.

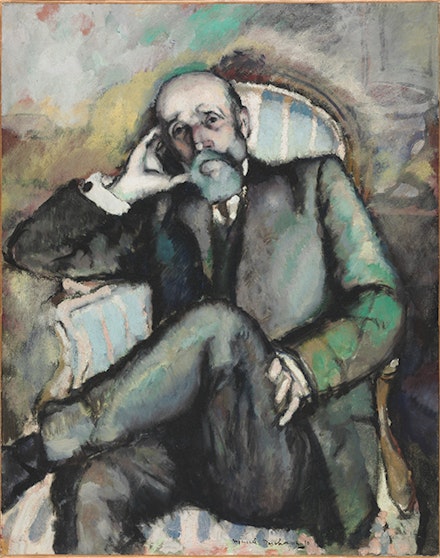

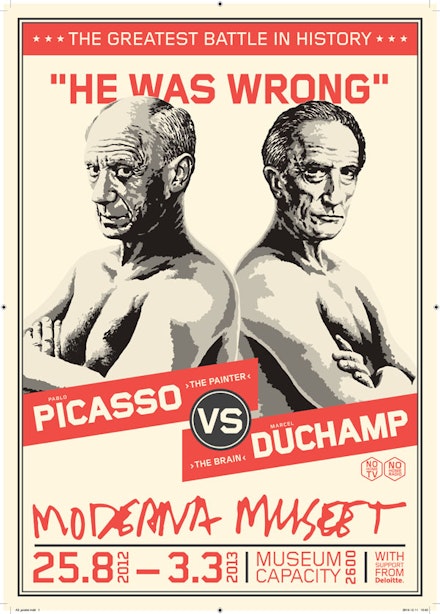

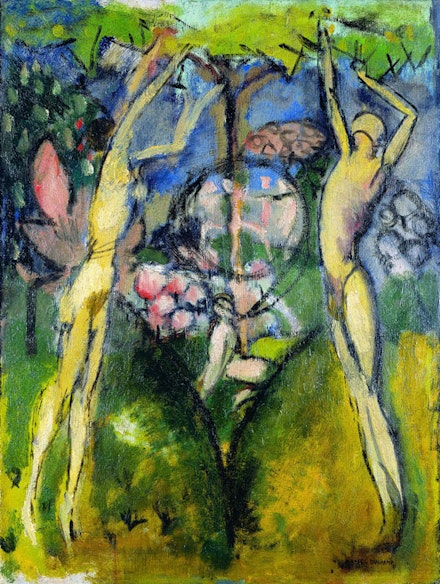

Despite the exhibition’s title, it soon becomes obvious that Duchamp did not love painting and painting did not love him. His early stabs at Fauvism are flaccid, uninspired, and imitative. Doubtless he had a revolutionary personality, but by the time he came of age the revolution was over. A generation younger than the Fauves and Cubists, he was in fact a contemporary of Chagall, not of Picasso and Matisse, who claimed that Cézanne was “the father of us all.” Apparently Duchamp originally agreed since he painted his father in a pose and style mimicking Cézanne’s portrait of own his father as well as a version of the “Bathers” based on Cézanne’s masterpiece.

The works in the exhibition make it clear that Duchamp understood Cézanne’s pictorial structure even less than he understood Fauvist color. Leger could build on Cubism to invent a contemporary style inspired not by still life or the figure but by machinery and architecture. But Duchamp was more interested in mechanical drawing and scientific diagrams, literature, and philosophy than Leger, who maintained that painters were stupid, a limitation Duchamp refused to accept.

Having joined his brothers in Paris in 1904, Duchamp enrolled in the Académie Julian, where students were prepared for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts examination, which he failed. It was but the first of a string of humiliating failures. Their father insisted Gaston (Jacques Villon) study law and Raymond go to medical school. Neither finished their professional training and both dropped out to pursue art, although Gaston continued to attend law school for a time. With nothing better to do, Marcel returned to Rouen as an apprentice at La Vicomté printers—a job his family probably engineered—where he printed the engravings of his maternal grandfather, Emile Frédéric Nicolle, a successful businessman who also made prints. In 1905, at age 18, Duchamp enlisted in the army, knowing he would inevitably be drafted because France had universal conscription. Volunteers were allowed to serve less time so he spent only a year being trained as a soldier. His military service over, he returned to Paris to join his brothers, working briefly as a caricaturist.

Comparing the paintings Duchamp produced between 1907 when the term Cubism was invented and 1911 when Braque and Picasso codified them, it is obvious he did not understand the basis of their pictorial revolution, which established the roots of modernism. Indeed, one conclusion to be drawn from this exhibition is that Duchamp was never a modernist. His paintings are a prologue to something else that was highly original and unique but not truly part of the history of modern painting.

The show lacks the three great summits of his achievement, which Duchamp made sure can never be moved—“Tu m’,” his largest and final painting finished in 1918; the alchemical experiment “The Large Glass” of 1915 – 23; and “Etant donnés,” his last work, which occupied him from 1946 – 66. This turns out to be a plus. Seen only in reproduction, their physical absence focuses us on why and how Duchamp devoted the last 50 years of his life to making these infinitely complex summations of his thinking and experiments. This is what they have in common: a dedication to handmade craft and precision, an obsessive fixation on the act of seeing, a long period of gestation documented with copious notes and guides based on sources outside of art—many of which are on view in the exhibition—and a provocation to the viewer to decode their cryptic meanings.

If, as Claes Oldenburg maintained in his Notes, everything he did was the result of childhood interests, this fact is even more relevant in the case of Duchamp. Artists, real artists in any event, tend to be obsessional: Monet was obsessed with perfecting his garden, Duchamp with mechanical toys, technological innovation, robots, and movies. He was fascinated by the machines produced by the birth of the industrial age and visited the Museé Arts et Métiers in Paris where they were displayed. Science and medical museums featuring anatomy also drew his attention. From childhood the young Marcel was intrigued by how things are perceived, which is the domain of scientific optics and physics and not of aesthetics. How we see—a mental process—interested him at least as much if not more than what we see. This is one of the threads binding his works.

The layout of the exhibition reveals how each of his three major works sums up a period of inquiry, structuring his oeuvre into the three parts that are like the movements of a symphony or acts of a play. I do not think this is coincidental. Nor is the fact that Duchamp insured they would remain in the United States (“Tu m’” in the Société Anonyme collection at Yale, “The Large Glass” and “Etant donnés” at the Philadelphia Museum) and can only be seen elsewhere in reproduction. To see the originals, one must literally make a pilgrimage. Impossible to move, they are Duchamp’s last laugh: his revenge against second-hand experiences and reproductions.

Of the roughly 50 paintings in the show, it is significant that a large number are family portraits in one form or another culminating in the transitional 1911 – 12 “Sad Young Man on a Train,” which Duchamp identified as a self-portrait. He explained that his primary concern in this painting was the depiction of two intersecting movements: that of the train in which there is a young man smoking, and that of the lurching figure itself. He explained to Pierre Cabanne:

First, there’s the idea of the movement of the train, and then that of the sad young man who is in a corridor and who is moving about; thus there are two parallel movements corresponding to each other. Then, there is the distortion of the young man—I had called this elementary parallelism. It was a formal decomposition; that is, linear elements following each other like parallels and distorting the object. The object is completely stretched out, as if elastic. The lines follow each other in parallels, while changing subtly to form the movement, or the form of the young man in question.

These are issues Duchamp realizes more fully in the 1918 “Tu m’.” Visual paradox and this horizontal stretching out of the image correspond to Duchamp’s claim “to strain the laws of physics.” As his sources are gradually revealed, however, we find his images are based not on non-Euclidian geometry or the general theory of relativity, the great discoveries that were the talk of his youth, but on textbook illustrations of anatomy, mathematics, and physics, and the distortions of anamorphic perspective discovered in the 16th century.

At the meetings his brothers organized at their home in Puteaux outside of Paris, discussions might range from Robert Delaunay’s color theory to Poincare’s new mathematical theories to the latest arcane scientific discoveries. Most exciting for the group wishing to find a new frontier for Cubism was the possibility of a “fourth dimension,” first proposed by Englishman Charles Howard Hinton in 1882, which became a hot topic in Paris intellectual circles a quarter of a century later. A restless Duchamp soon tired of the chatter and stopped attending the meetings. In his interviews with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp implied that his understanding of the fourth dimension basically was the science fiction version described by Gaston Pawlowski in Voyage au pays de la quatrième dimension.

Pawlowski’s novel was no paean to the wonders of technological progress. Rather it was a critique and caricature of new-fangled gadgets like a bathtub entered laterally, a tape measure that could only measure 10 centimeters and a boomerang that did not return to the person who threw it “for reasons of safety.” The same year Pawlowski published his science fiction fantasy of the fourth dimension describing a train trip, Duchamp began his first mecanomorphic painting, “Sad Young Man on a Train,” in which the human figure begins to morph into a machine. Duchamp always maintained that his titles add important meaning to his work. If so, we may ask, why is the young man, who is Duchamp himself, so sad? Perhaps because the train—motorized transportation—is taking him from Rouen to Paris, from the provinces to the capital, from the country to the city, with each lurch forward distancing him farther from home and family.

Also painted in 1911, “Young Girl and Man in Spring” is still softly pastel. Its subject, two transported young lovers, is both symbolic and romantic, states of mind Duchamp became increasingly determined to discard for their old-fashioned sentimentality, replacing them with cold unemotional mechanical eroticism that served to mask his own feelings as well. In fact, in April 1910, Duchamp became romantically involved with the model, Jeanne Serre. Because she was married, there was no pressure on him for a permanent relationship or family responsibilities. Nevertheless, in February Jeanne gave birth to a daughter, who was generally presumed to be Duchamp’s child, although he made no effort to see her or have any further contact with her mother.

The years 1911 – 12 are the apogee of Duchamp’s career as a painter. Beginning with “Sad Young Man on a Train” the paintings of this period include “The Passage from Virgin to Bride,” “The Bride,” the two versions of the “Nude Descending the Staircase,” and “King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes” of 1912. One reading of the iconography of this painting is that the king and queen, both chess pieces, refer to Duchamp’s parents surrounded by the swift nudes who are the children. Indeed, during his fateful trip to the Jura Mountains with Apollinaire, Picabia, and Gabrielle Buffet—Picabia’s wife with whom he was apparently infatuated—Duchamp wrote notes that became the basis of the iconography of “The Large Glass.” One describes a game played like chess with two teams, one of which was made up of five nudes and a leader who instructed them. It is hard not to imagine that the five nudes were Duchamp’s siblings and that he thought of himself as the leader of their tribe.

“The Passage from Virgin to Bride” and “The Bride” do not allude to the body itself but rather to the interior system of veins, arteries, and organs—images inspired by the contemporary anatomical treatises and wax models in the exhibition. In Duchamp’s painted “Bride” we see the guts of the nude, the machinery that keeps the body alive. Basically flayed open, Duchamp’s mechanical women are in no way seductive. They are the realization of the prophecy of Villiers de l’Isle Adam in La Nouvelle Eve (The New Eve) that the women of the future would be robots. Duchamp was not a misogynist like the hardcore Surrealists with whom he exhibited from time to time. But the popularity of the idea of a mechanical doll, an electrified Copelia or a neutered mannequin was part of the fantasy life of the men of his generation.

As in the “The Passage from Virgin to Bride,” the titles of the paintings of 1912 relate to the various passages of female life. But he avoided the completion of that ultimate female anatomical passage—which Freud identified as the destiny of women—the passage from the bride to the mother in both life and art. He may have played the transvestite, inventing the coy Rrose Sélavy as a female alter ego, but there is no evidence Duchamp was interested in men. On the contrary, beginning in 1923, he had three serious long-term overlapping relationships with women. All well-to-do, thus needing no support, already married, widowed, or divorced, so they could be neither virgins nor brides, and all beyond childbearing age, so incapable of producing a bothersome baby.

Duchamp’s first “machine” painting, the 1911 oil-on-board coffee grinder—which he originally gave to his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon for his kitchen—was also made in the period of 1911 – 12. An informal study, it depicts the motion of the grinding mechanism in various positions. Overall, the paintings of this brief period are fully realized despite their rejection of visible brushstrokes and the tonal passages and illusionistic space that have more in common with the lacquered surfaces and modeling of old master painting than with modern art. Duchamp’s paintings are anything but fresh and spontaneous. They are deliberate and thought out, based on preliminary drawings which are also on view. The many drawings both notational and finished are among the delights of the show. As a draftsman Duchamp had a light but sure hand.

The exhibition includes examples of motion photography by Muybridge, Marey, and others that inspired Duchamp’s ambulatory “Nude” seen in successive positions. The Futurists, who were obsessed with movement, had their first group show in Paris in February 1912, which Duchamp must have seen. Indeed “Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2” is much closer to the motion studies of Futurism than to the static images of Cubism, the reason that the chauvinistic French organizers of the 1912 Salon des Independent rejected it. Of the incident Duchamp later recalled, “I said nothing to my brothers. But I went immediately to the show and took my painting home in a taxi. It was really a turning point in my life, I can assure you.” He would paint little after this painful rejection. He made a decision to be alone: “Everyone for himself, as in a shipwreck” is how he put it.

Stinging from his rejection in Paris, Duchamp accepted the invitation of his friend Max Bergmann to visit Munich. He arrived on June 21, 1912 and found a 10-square-meter flat to live and work in on Barer Straße 65. He stayed for three months that summer freeing himself from Cubism and developing his ideas for “The Large Glass,” a work that would go beyond painting. He later explained: “My stay in Munich was the scene of my complete liberation.” But that is about all he had to say of the German experience that changed his life or at least his art.

Munich was a lively and strange mixture of a variety of metaphysical ideas. There were artists and thinkers from other parts of Europe like the brothers Burliuk, Kandinsky, and de Chirico. According to Mein Kampf Hitler arrived in Munich in May 1912 to study architecture. But he was not accepted by the Academie des Beaux-Arts so he did not stay. When Apollinaire asked for a portrait to illustrate Les Peintres cubistes, Duchamp chose to be photographed by the most famous photographer in Munich, Heinrich Hoffman, who later became Hitler’s personal photographer. What really happened in those three crucial months of seclusion in Munich is still a matter of conjecture. Duchamp avoided ever talking about his experience in Munich and the poker faced, closed mouth appearance in the Hoffman photograph is an indication of that attitude.

He wanted a complete break from the Parisian scene and a way to take painting somewhere it had never been. At the Deutsches Museum and the Bavarian Trade Fair, he discovered important technical details that inspired his readymades, which he began the following year in Paris. Not speaking the language apparently did not deter Duchamp from moving to a new city. For example, when he decided to move to New York in 1915, according to Man Ray, he spoke not a word of English. During his three months in Buenos Aires in 1918 he could not speak Spanish. In fact he once said that not knowing a language was the best way to think independently.

In Munich, Duchamp made four drawings for “The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors”; two drawings for “The Virgin”; a sketch for an “Aeroplane”; and the paintings “The Bride” and “The Passage from Virgin to Bride.” He visited Munich’s great old master collection in the Alte Pinakothek every day. In fact, visiting museums seems to be what he did most of the time. The paintings he made in Munich were influenced by the works of the 16th-century German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder that he saw there. Duchamp told Richard Hamilton that he painted in Munich with his fingertips because he knew how Cranach used his fingers and the palms of his hands to paint his shiny slick surfaces that eliminated any trace of brushwork.

The paintings Duchamp made in Munich have little if anything to do with Cubism. Indeed he was never a Cubist. His forms are not fractured and recomposed but rather they are subtly modeled with passages of old master-like chiaroscuro. In “The Passage from Virgin to Bride” semi-organic and semi-mechanical forms suggest fleshly vessels, armatures, and veins. The organs, ducts, and tubes have fluctuating contours compressed in a shallow space that is not however the superimposed planes and frontality of Cubism.

Duchamp’s concentration was on the inner tubing and organs of the body’s anatomy rather than on its outward envelope of soft flesh and skin. While he must have known Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, observations of the interior of the human body became concrete documents with the discovery of the x-ray by German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in 1895. Three years earlier in Paris, Albert Londe invented a chronophotography machine to visualize the physical and muscular movements of patients by using a camera with nine lenses able to sequentially time the release of the shutters. The better-known pioneer of stop motion photography, Étienne-Jules Marey, was in fact a physiologist who broke down movement in order to study muscle and bone function. Duchamp surely knew Marey’s physiological studies of biomechanical movement.

The idea was such a novelty that the pioneer filmmakers, the Lumiere brothers, had a show of x-ray images in their theater. In fact, Auguste Lumière’s primary interest was not film but medical technology. Done with moving pictures, in 1910, he operated the first x-ray machine in France as director of the radiology department at the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in Lyon. Chronophotography, motion pictures, and x-ray technology are related discoveries that were new and exciting, especially to the young Duchamp eager to find directions for artistic innovation that did not take painting as a futuristic point of departure. Ironically, the painting style he developed in Munich did not look forward to abstraction but backward at the meticulous polished surfaces of Northern Renaissance painting featured in Munich’s Alte Pinakothek.

In 1912, Munich was full of mysteries, the capital of occultism, and the spiritual underground. The city was packed with kooks talking about extrasensory perception like Gabriel von Max, who painted portraits of sleepwalkers and spirits, and his brother, photographer Heinrich von Max, who took photos of mediums in trance. It was also a headquarters for the Theosophical Society which taught Annie Besant’s theory that the mind created abstract “thought forms.” And, there was a Museum of Alchemy, later the Deutsches Museum. Kandinsky wrote his treatise on Concerning the Spiritual in Art inspired by Theosophy in Munich and Duchamp immediately bought a copy.

Little is known about Duchamp’s Munich sojourn possibly because he thought his adventures in occultism, magic, and alchemy should be hidden since they were highly suspect in Paris as irrational and also perhaps because they provide the basis of the iconography of “The Large Glass,” including the halo around the bride that can be imagined as an astral Theosophical “thought form” aura.

In fall of 1913, “Nude Descending the Staircase, no. 2” was chosen by Walter Pach to be sent to New York to be hung in the Armory Show that introduced modern art to the United States. Duchamp’s iconic painting created a sensation, probably because of its title, since the image was no more scandalous than any other Cubist or Futurist work exhibited. In 1913, Americans were still averse to nakedness. Their idea of “fine art” included studio nudes.

Duchamp did not attend the opening of the Armory Show in New York. In 1913, his mind on matters other than painting, he took a job as a librarian at the Bibliotheque Sainte-Geneviève where collections of early manuscripts and books were housed. During the next two years he spent his spare time (which seems to have been all of his time) reading scientific and aesthetic texts and treatises. One of the notes in The Green Box containing the studies for the “Large Glass” says: “Perspective. See the catalogue of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. The whole section on perspective: Nicéron (Father J. -F.), Thaumaturgus opticus.” Many of the books Duchamp consulted at the Bibliotheque Sainte Genevieve are included in the exhibition. They contain word games, perception games, visual puns, and descriptions of both real and fake science. Meanwhile, in his studio he created a “Readymade” by mounting a bicycle wheel on a kitchen stool, very likely inspired by Comte de Lautréamont’s idea of a chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table, a source for Surrealist juxtapositions of common objects.

Duchamp’s epiphany that painting was dead occurred, according to Leger, at the Salon de la Locomotion Aérienne, which took place at the Grand Palais in Paris from October 26 to November 10 in 1912. Leger later recalled:

I went to see the Air Show with Marcel Duchamp and Brâncuși. Marcel was a dry fellow who had something elusive about him. He was strolling amid the motors and propellers, not saying a word. Then, all of a sudden, he turned to Brâncuși, “It’s all over for painting. Who could better that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?”

It turned out that with the “Bird in Space” Brâncuși, who had become a close friend, could, which accounts for why Duchamp spent so much of his time and his own money promoting and selling Brâncuși’s sculptures.

Among the texts and illustrations from contemporary publications on view in the show is an early edition of Raymond Roussel’s 1910 novel, Impressions d’Afrique. Duchamp credits Roussel’s images of humanoid machines and an android heroine as his initial inspiration for “The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even,” the full title of “The Large Glass.” How much time Duchamp actually spent studying Poincaré, non-Euclidean geometry, or Einstein’s general theory of relativity is not known. However, the visual evidence leads one to conclude it was not science but science fiction that inspired him.

The Armory Show scandal meant that Duchamp was already famous when he debarked in New York in 1915 apparently to avoid any possibility of being drafted despite the fact that officially he had a heart murmur. In New York, he would continue to develop the transparent glass for “Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even” in secret for the next eight years. In the meantime, he scandalized the New York art world by submitting a mass produced urinal as a sculpture to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent artists. Unlike the Paris salons, the New York group exhibition presumably accepted anything submitted by an artist. Typically, Duchamp upped the ante. If the Paris salon rejected his painting, he would submit a “sculpture” to the New York salon that would challenge the tolerance of the Americans by calling an ordinary mass-produced found object art. “Fountain,” the title for the urinal, an object referring to private bodily processes, once again made headlines.

Pawlowski’s was a cynical vision of a world in a state of transformation from an agricultural culture to an industrialized machine age. Duchamp keenly felt the loss of the agrarian handmade culture into which he was born and its replacement by the machines and motors of industrial progress. This nostalgia never left him; although he lived in cities, he vacationed in the country. Even in New York he spent weekends in the country in Connecticut with his friends Alexander Calder, Hans Richter, and the heiress he turned into a major art collector, Katherine Dreier, who apparently along with Peggy Guggenheim, another wealthy Jewish art patron, found Duchamp irresistible. And there is no denying he used his powers of seduction to good advantage. Personally he wanted nothing to do with money. On the other hand even his austere existence and his generous support of other artists required it.

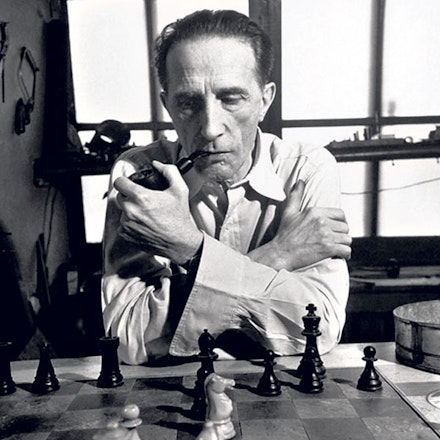

In the meantime, he continued his investigation of alchemical themes in “The Large Glass” secretly taking shape in his studio. Because there is a constant overlap and continuity in Duchamp’s thinking that links all his works together in a continuous narrative, separating the paintings from the rest of his work is possible only in terms of medium. When asked what he was doing, Duchamp would explain he was playing chess, although he did claim a number of found objects as art during his stay in New York. In 1918, Katherine Dreier commissioned a mural on canvas which became the infamous “Tu m’,” ending Duchamp’s career as a painter, although he continued to draw. “Tu m’” combines real objects with the shadows cast by objects outside in real space. This is clearly illustrated in the exhibition by the presence of the suspended readymades, the bicycle wheel, bottle rack, and four-pronged hat rack, which are present in the painting only as shadows of themselves. These objects are like Duchamp himself: they are there and simultaneously not there. He is omnipresent in his comic self-advertisements, yet he sees mainly his intimate circle, lifelong friends and relatives.

In “Tu m’,” Duchamp plays with real and represented objects as well as with real and virtual space suggested by the shadows of objects that are not present and with different intersecting skewed perspectives. To further complicate the issues, he paints a trompe l’oeil tear in the surface of the canvas held together by real safety pins. In addition, a bristly bottlebrush—presumably to clean the bottles absent from the bottle rack present only in shadow—juts out from the tear at a right angle to the canvas. Duchamp further emphasizes the spatial oddities of his picture by using various forms of “intersection.” The corkscrew intersects the canvas; the safety pins pierce the surface of the canvas. The real bottlebrush and a bolt, fastened to the back of the canvas, pierce the front.

The distortions that arise from the intersection of depicted and real objects with the painted shadows of the readymades not present in the painting and an abstract color chart of overlaid squares diminishing in size refers to the warped perspective of an old master painting that is a secret Vanitas. There is no skull in “Tu m’,” but as Jean Clair was the first to point out the perspective in “Tu m’”is not that of the Italian Renaissance but the anamorphic perspective of the hidden skull in Holbein’s “Ambassadors,” a theme taken up again later by Jasper Johns. According to Clair, organizer of the Centre Pompidou’s first Duchamp exhibition in 1977, the function of the bottlebrush is similar to that of the skull in Holbein’s picture: namely, “to expose the vanity of the painting. But this time of all paintings.”

Anamorphic images are distorted projections of an image that to be recognized must be viewed from a position different from the usual frontal position from which we normally view paintings. Holbein’s distorted skull placed in the bottom center of the composition is stretched out horizontally until it is unrecognizable except from the side. Duchamp was very attentive to Leonardo da Vinci, once again looking back for inspiration. Leonardo made the first anamorphic projection in a drawing of an eye in 1485. The truth is Duchamp was an intellectual bookworm of immense curiosity. His sources include scientific and mathematical textbooks and their diagrams, some of which are in the show. He was also very taken with the idea of alchemy as a hermetic crypto-science. Alchemy involves the transformation of base metals like lead, the material of “The Large Glass,” into gold and links Duchamp both to the tradition of the trickster Hermes Trismegistis, the original alchemist, as well as to Yves Klein and James Lee Byars, who were equally involved in such pursuits.

Jean Clair saw a reason for Duchamp’s decision to stop painting other than boredom:

He had painted, in Munich, the “Bride,” which is in every respect his masterpiece. The chromatic finesse of the grays and the ochre, the declination of the reds and the greens, a lesson in anatomy without precedent ... a work of infinite charm which placed Duchamp right away in the ranks of the great masters. He had established his supremacy. Abandoning the pigments and their bond with the earth, he chose the materials of a laboratory, the glass of test tubes and vials.

Duchamp admitted to Pierre Cabanne that he wished to leave New York because the U.S. had entered the war and he wanted nothing to do with it. In the summer of 1918 newspapers were filled with the news that American soldiers arrived in large numbers on the Western Front. In July, Duchamp finished “Tu m’,” and on August 14, 1918 he sailed for Buenos Aires on the SS Crofton Hall. He arrived in Buenos Aires on September 9, 1918. A month later Raymond Duchamp-Villon died, age 41, in an army hospital in Cannes of an infection contracted while working as a medic at military headquarters in Champagne.

Apparently with the idea in mind that Roussel had written about Buenos Aires as an exotic destination in Locus Solus, Duchamp left New York with Yvonne Chastel, the estranged wife of Jean Crotti, a Swiss artist soon to marry Marcel’s sister Suzanne in Paris. Duchamp wrote Crotti that the purpose of the trip to South America was “to cut entirely with this part of the world.” He imagined Buenos Aires as a kind of sunny New York, but he was soon disappointed with its copy of European culture and mediocre bourgeoisie and bored with the theaters and tango palaces. He continued to make notes and sketches for “The Large Glass,” intending to complete it in New York. His letters to friends reveal a growing disenchantment and as for latin machismo, “the insolence and folly of men,” he found offensive. He returned to Paris in early 1919 after the armistice was signed and continued the theme of the readymade, with the idea of the “assisted” readymade in the “rectified” “Mona Lisa.” His trip to Paris that year was his first visit to the city after spending four years in New York and nine months in Argentina. He stayed only five months and then was back in New York in 1920 to resume work on “The Large Glass” in secret. Officially, he was playing chess.

“The Large Glass” is impressive in many respects. Over nine feet tall, it is a transparent freestanding object, fusing two glass plates with figures in lead inlaid between them. It is neither painting nor sculpture. Its neither/nor status is a basic part of its identity. Like the estranged states associated—or disassociated—with Surrealism, “The Large Glass” is “something else”—a fantasy as literary as it is visual. Duchamp’s mysterious recondite science turns out to be science fiction, the machinery of a Rube Goldberg contraption mocking progress. Not only an object but also an occasion for meditation and free association, “The Large Glass” is deliberately difficult to decipher. Duchamp intended it to be accompanied by a book, which like a manual instructs the viewer about the rules of the game. The notes, published as The Green Box, describe that his “hilarious picture” is intended to depict the erotic encounter between the “Bride” in the upper panel, and her nine “Bachelors” gathered timidly below, a mysterious mechanical phalanx of suitors in the lower panel.

In 1923, considering “The Large Glass” “definitively unfinished,” Duchamp returned to France ostensibly to devote himself to playing chess in professional tournaments. He took time, however, to continue his study of motion begun with the futuristic “Nude” in films he made with the help of Man Ray, who he had met in the United States. He settled down in Paris and began a romantic relationship that lasted 20 years with Mary Reynolds, a gentle, kind, intellectual American expatriate. But suddenly he surprised his friends by marrying Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, a woman Picabia introduced him to in 1927. The marriage, which lasted seven months, is documented by Duchamp’s unfortunate first wife in a guileless memoir titled Un Echec Matrimonial—the failure of a marriage. Is it a coincidence that chess in French can be interpreted as a double entendre for failure?

There was not much pretense about the fact that Marcel had to marry Lydie, who Carrie Stettheimer accurately referred to as “fat,” because he was for the first time dead broke. His parents had both died in 1925. As long as they lived he had a small pension, but he spent his even smaller inheritance buying Brâncuși’s unsalable sculptures, thus protecting Brâncuși and his work but leaving himself penniless. It was soon clear that Duchamp preferred chess to his wife. Once she realized this, she glued his chess pieces to the board in their Rue Larrey garret. This was pretty much the end of his brief first marriage, which seems to have overlapped with his continuing relationship with Mary Reynolds anyway. After his divorce, Duchamp permitted Reynolds, who was a young widow, to be seen with him in public, but he would neither marry her nor live with her full time.

Playing chess steadily, he definitely improved his game. In 1932 he was named French delegate to the International Chess Federation and won the Paris chess tournament. He found time, however, between 1925 and 1935 to experiment with kinetic art and to collaborate with Man Ray to make films. “The movies amused me because of their optical side,” he told Katherine Kuh:

Instead of making a machine which would turn, as I had done in New York I said to myself, Why not turn the film? That would be a lot simpler. I wasn’t interested in making movies as such; it was simply a more practical way of achieving my optical results. When people say that I’ve made movies, I answer that, no, I haven’t, that it was a convenient method—I’m particularly sure of that now—of arriving at what I wanted. Furthermore, the movies were fun.

La Peinture, Meme includes films by Man Ray, Leger, and Brâncuși, in addition to Duchamp’s own Anemic Cinema. Film, of course, is a collaborative process and in making and appearing in films, Duchamp found many playmates. He himself only became a movie star in Hans Richter’s films, but he and Man Ray conspired to turn Duchamp into an advertisement for himself. He was a star without a vehicle but he was famous, the first artist to invent a cult of personality that later inspired theatrical types like Warhol and Beuys. He was happy to be photographed by anybody from Stieglitz to Man Ray to Richard Avedon. Poker faced, he is expressionless until the late laughing and mocking photographs. The carefully staged photographs are the public face of the private man determined that no one know his vulnerabilities.

During the ’30s he went back and forth between New York and Paris and produced the Boîte-en-valise, the portable museum of miniatures of his works, probably inspired by the circus suitcase designed by his friend Alexander Calder to house his miniature transatlantic traveling circus. With Mary Reynolds he designed exquisite unique bookbindings for avant-garde authors, which are now in the Art Institute of Chicago. When the Germans occupied Paris in 1942, Reynolds chose to stay although Duchamp tried to convince her to leave with him for the United States. With the code name “Gentle Mary,” she joined a résistance group which included Samuel Beckett and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia. Under Gestapo surveillance beginning in the summer of 1942, she was forced to flee France. Leaving via Madrid, she finally arrived in New York in 1943. By that time, however, Duchamp had begun his ill-fated romance with Maria Martins, the socialite surrealist sculptor and wife of the Brazilian ambassador to the U.S.

No two women could be more unlike than the two Marys. Reynolds was a heroic, selfless, modest but perfectionist creator of elegant and refined bookbindings. In Maria Martins, the great seductress, the great seducer met his match. He had broken the hearts of many women, but in a drawing for Martins, he was so smitten that he drew a red heart below a French inscription that begged her not to crush it. Martins was an aggressive domineering femme fatale who had already caused her teacher Jacques Lipchitz to have a nervous breakdown when Duchamp met her. In Washington, she turned the top floor of the embassy into a sculpture studio, but D.C. could not accommodate her ambitions, either erotic or artistic. So she left her family in Washington and rented a duplex on Park Avenue where she lived in luxe and gave glamorous parties.

Maria Martins’s sculptures and her Time magazine interviews are truly embarrassing, a proof that love is blind. Duchamp’s “New Eve” is not the passive mechanical doll set into motion but a voracious Brazilian temptress, a feminist avant la lettre who has found her inner goddess in the form of Yara of the Amazon, the subject of an over life-size sculpture that appears to be a nude self-portrait. Their tumultuous affair is a cliché resembling a bad Hollywood noir movie. This is a conclusion to be drawn from her incredibly kitsch poetry: “I want to see you lost, asphyxiated, wander in the murky haze woven by my desires,” she wrote. “For you, I want long sleepless nights, filled by the roaring tom-tom of storms. Far away, invisible, unknown. Then, I want the nostalgia of my presence to paralyze you.”

Exulting in the idea that she was a Venus flytrap, Martins caught Duchamp in her web and had him in her thrall until 1950 when she moved back to Brazil with her husband and three children. That same year Mary Reynolds, who had returned to Paris in 1945, died. Duchamp was crushed. His correspondence with Maria Martins, secret for years, was made public in the Philadelphia Museum catalogue for “Etant donnés.” Her nude body, which Duchamp cast in a long series of trial-and-error projects, is the focus of “Etant donnés,” Duchamp’s last work, which occupied him for 20 years from 1946 until 1966.

With “Etant donnés” Duchamp came full circle, recuperating his past and all that had concerned him from his early years beginning with the racy scenes of the 19th-century stereoscope peepshow. The divider or other view-limiting feature that prevents each eye from being distracted from seeing the image intended for the other eye now takes the form of two holes in a wooden door that seals in the bizarre tableau. But this peep show has grisly qualities. This “nude” is not only not seductive, it is repulsive with its splayed legs and gash-like hairless vagina.

“Etant donnés” is a further recapitulation of his obsessions with voyeurism, movement, representation, and mechanization. This time, however the bride is transformed not into a machine but into a corpse in a strange kind of anatomy lesson. Installed after Duchamp’s death in 1968, “Etant donnés” has given rise to its own interpretation industry. Duchamp intended it to be enigmatic and multivalent and surely it is. There is no “one” way of seeing or interpreting it. That the position of the nude was changed is certain. In the original drawings and studies Maria Martins is upright, standing on one foot with her leg raised in the air in a pose similar to that of a dog urinating, probably the only way a woman could use a men’s urinal. Finally, a purpose has been found for “Fountain.”

Over the period of 20 years during which this work was laboriously made, the original casts of Maria Martins’s body ended up as a composite of fragments. The one new body part specifically identified as such is the arm that holds aloft the torch, which was cast from the arm of Duchamp’s second wife, Alexina (Teeny) Sattler. It is reminiscent of the torch of freedom of the Statue of Liberty that had welcomed Duchamp twice, in 1915 and 1942, which is appropriate since he became an American citizen in 1955. The nude we see through the peepholes has her face obscured by a blonde wig—the color of Teeny Duchamp’s hair—rather than the original brown wig associated with Maria. The nude is no longer upright but spread out vertically. She is now literally a “reclining” nude.

Previously, Duchamp deliberately created questions regarding his sexuality in provocative photographs of himself dressed in drag as his alter ego, “Rrose Selavy.” On the other hand, cross-dressing was a fairly common avant-garde activity. Artists like the American synchromist Morgan Russell had themselves photographed in women’s clothing as a daring charade. There is one account that Duchamp participated in an orgy with three women organized by his close friend the novelist Henri-Pierre Roché. Ultimately, he confessed to Pierre Cabanne, he was boringly normal. He intentionally distanced himself from romantic sentimentality. But the truth is, as the inscription to Martins reveals, he was sentimental and romantic. He was also unhappy because as much as he valued his freedom and solitude, he wanted a playmate like his siblings, especially his sister Suzanne, his favorite playmate. However, it not only takes two to tango, but also to play chess, which was one way to find at least a temporary playmate. Leaving his work open to any and all interpretations was his way of enticing the viewer to become the absent playmate.

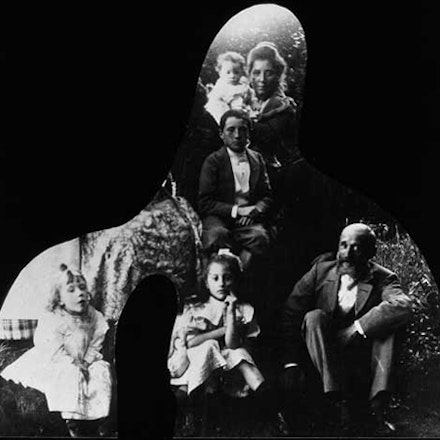

Duchamp missed the warm atmosphere of his original tight-knit family, which closely resembles the psychological profile Freud described in his essay on “The Family Romance.” Reasserting his own place as the center of attention, in 1964 he made collage of the original 1899 photograph of the Duchamp family with his three younger sisters and two older brothers, masking out Gaston and Raymond by cutting the photograph in the shape of the urinal, leaving himself as the center of attention. At the same time, he honored his brothers and in 1967 organized an exhibition Les Duchamps that included their work along with his own and that of Suzanne. The work of all the family members is appropriately also part of the Centre Pompidou exhibition.

Recovering from the loss of both Maria and Mary, Duchamp finally found his ideal playmate in Teeny Sattler, the ex-wife and mother of Pierre Matisse’s children, whom he met in 1951 and married in 1954. The melancholic, sad young man became a contented and satisfied old man as the stepfather of Matisse’s grandchildren, who were devoted to him. The family had been reconstituted. Teeny was even able to persuade him to meet his own daughter, a painter who signed her works Yo Serremayer, and Duchamp organized an exhibition of her work at the Bodley Gallery in New York.

With her immense charm and discretion—she was universally beloved—Teeny had the lack of pretension, generosity, and warmth that were the reality behind the mask of the faux persona Duchamp had created, encased by the hard shell of the uniform of the bachelors in “The Large Glass” he assumed to protect the hypersensitive vulnerable poet inside from rejection and loss. Never free from his original family but unable, until the end of his life, to have a family of his own, Duchamp emerges from this exhibition as a product of his time and experience, a lonely, melancholy, fragile man who signed letters to those he knew well “affectionately, Marcel.”

The idea that he was strategic and deliberately seeking to shock is contradicted by the statement he made to Katherine Kuh in 1962: “The strange thing about readymades is that I’ve never been able to come up with a definition or an explanation that fully satisfies me.” He claimed he had no artistic intention when he fastened a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool in 1913, “I didn’t want to make a piece out of it, you see ... there was no conception of readymade nor of anything else, it was just a distraction. I didn’t have a specific reason for doing so, or any intention of an exhibition, or description.” He was not a cold strategist but in many respects a merry prankster in search of relief from loneliness. He inhabits no real laboratory but the alternate universe of jokesters and tricksters of Alfred Jarry’s pataphysique, which Duchamp admitted was an inspiration.

The pose of not being serious left Duchamp off the hook in terms of critical judgment. But it was also a façade. Hardly the lazy flaneur or the amoral gigolo he would let the world believe he was, in fact he was deeply serious, working constantly even when officially doing nothing but playing chess. What he achieved was neither easy nor superficial, the transformation not of reality but literary fantasy into art in which the actual physically present materials and their forms and space are at least as, if not more, important than the iconography and the stories they tell. Intentionally left open to multiple, even conflicting, interpretations, his objects and writings have become an international tournament of interpretation and a veritable academic industry.

By putting together The Green Box, the notes for “The Large Glass,” and The White Box with material related to “Etant donnés,” and then the notebook with the precise guide of how to install the contents of “Etant donnés,” he provided guides to the rules of the game. By now there are probably more people playing the international Duchamp Game than the entire population of Rouen, where Duchamp, Teeny, and all of Marcel’s siblings are buried. But it’s a great game, more fun than chess and far more intimate and revealing. Your move, Marcel.

The sources I have relied on include Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont’s extensive research compiled for the Moderna Museet, Francis Naumann’s essays and compilation of Duchamp’s letters, and Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal. For any discussion of the fourth dimension, Linda Henderson’s book on the subject is indispensible. Gradually more and more of Duchamp’s correspondence has been published in French and English clarifying his life and thought. The Philadelphia Museum exhibition of “Etant donnés” includes for the first time the correspondence with Maria Martins. I also learned a great deal from the catalogue for the first Centre Pompidou exhibition in 1977, published in four volumes, as well as the excellent catalogue for the current show. The literature is so vast on Duchamp that volumes would be necessary simply to list the titles.

Post Script

I met Marcel Duchamp on a number of occasions. He was, as many have observed, charming, courteous, unpretentious, elegant, and diffident or possibly just amused. I was first introduced to him at the opening of the 50th anniversary of the Armory Show in April, 1963. He was not yet quite the hero he would be, but certainly no longer considered the imposter and hoax the papers pictured him as in 1913. My Ph.D. oral exams were the next day and Professor Julius Held, who was on my committee, was astonished I was not home cramming. I should have been but I was dying to meet Marcel Duchamp, the mysterious figure who occasionally would turn up at Happenings.

At the time he was mainly known as a Dadaist or a Surrealist. His stance of being retired from art having been accepted, no one had any idea he was working on an infinitely complex installation in secret. When Walter Hopps organized the first Duchamp exhibition in October of that year at the Pasadena Art Museum, I managed to get there and again shake hands, but this time also to see a lot of work I had never seen before, which I admired for its craftsmanship and opaque enigma. Fascinated, I too could not help but want to come and play with Duchamp. One evening John Cage asked me if I would like to visit Marcel and play chess. I said I would like to visit Marcel and Teeny but I was not going to embarrass myself by playing chess. Instead I watched Duchamp play chess with John Cage, who was never embarrassed by anything.

As impressed as I was by Duchamp’s charm and intelligence and his ability to stay clear of the art market and the intrigues of the art world, I was angry he convinced so many that painting was dead, since above all, I loved painting. I got over this moment of pique because I was intrigued by his imagination and inventiveness. What Duchamp himself had done was always interesting and provocative. What was done in his name, on the other hand, was responsible for some of the silliest, most inane, most vulgar non-art still being produced by ignorant and lazy artists whose thinking stops with the idea of putting a found object in a museum.

In 1971, fed up with everybody and everything, I took a job as director of the art gallery of the University of California, Irvine. With my colleague Moira Roth, a Duchamp scholar, I organized an exhibition and symposium titled Marcel Duchamp: Choice and Chance. I thought Duchamp should be present throughout the show. With the hare-brained idea in mind for an interdisciplinary participatory media-oriented exhibition, I spent months making tapes with everyone who knew Duchamp who was still alive, including John Cage and Jasper Johns. I flew to Mexico to interview Octavio Paz, who had been very close to Duchamp. I borrowed copies of Duchamp’s films and rotoreliefs. Hans Richter loaned me his movies featuring Duchamp, including the then unfinished Dreams That Money Can Buy. I accumulated slides of every image by and of Duchamp and every sound recording he made that I could locate so his voice and image were constantly present throughout the exhibition.

Then I made the mistake of taking Apollinaire’s idea that Duchamp would be the artist to unite art and the people seriously. I gave my students the assignment of creating Duchamp awareness all over the Irvine campus, which accommodated graduate engineering and science schools as well as the liberal arts and humanities. When they showed up dressed as cheerleaders waving pompoms chanting, “Marcel is still da Champ, Marcel is still da Champ,” I knew I had lost that round. But I was sure that the symposium of experts like Anne D’Harnoncourt, Richard Hamilton, Kynaston McShine, Nan Rosenthal, and Annette Michelson, which I had videotaped, would be stimulating and edifying. The tapes are lost, but Walter Hopps’s contribution was unforgettable. The students, impatiently wearing buttons saying “Walter Hopps will be here in twenty minutes,” were restless by the time Walter ran down the aisle to the stage and grabbed the microphone. He spoke for more than half an hour, but all he talked about was how at the age of 11 he had visited the home of Duchamp’s great patron Walter Arensberg in Pasadena. We anxiously awaited the climax, which was that after climbing many flights of stairs Walter came to a door and knocked on it. The door opened and a man in a robe was standing there. Breathless now, Walter said, “I asked, are you Marcel? And the man said yes.” That was the end of the lecture. I think Duchamp would have loved it.