Professor John F. Potter BSc, PhD, FGS, CBiol, FSB, FIEnvSc

6th July 1932 – 27th November 2019

A note from the Publisher:

We were greatly saddened to hear of the passing of our friend and colleague Professor John F. Potter in late 2019. John had been a regular collaborator with Archaeopress and we shall miss his visits to our office very much. We were very far into production for John’s latest title Bar Locks and Early Church Security in the British Isles when he died and, with the kind permission and co-operation of his family, were able to complete the project for final publication. The book is published in our Access Archaeology imprint where the PDF eBook can be downloaded free of charge. A printed paperback edition is also available, priced £40.00.

We are very pleased to present the introduction below, along with a link to continue reading via the free PDF download.

Bar Locks and Early Church Security in the British Isles

John F. Potter

Chapter One. Keys and Bar Locks

The evolution of this study

Forty plus years of detailed study of the fabrics and structures of early Christian ecclesiastical sites and buildings, throughout the British Isles have led the author to some unexpected discoveries.[1] One, in particular, has been that very little examination, discussion or observation has been made as to how the earlier of these buildings were made secure when they were first built. That castles should possess defensive features such as the moat, drawbridge, portcullis and thick walls, all constructed to provide defence and security, has never been questioned. In 2004, Harrison in a description of many of the larger, predominantly monastic, religious structures in the northern hemisphere described them as ‘Castles of God’ and that ‘architecturally, the ecclesiastical edifice is subservient to the military’.[2] Early churches, perhaps erected at much the same time and on occasions presumably in the possession of valuables, would often appear to remain lacking in any similar level of protection.

The populace at large today, and most persons associated with churches, including those whose work or study embraces these churches, in response to comment or the question as to how the early protection of the buildings was accomplished, may well answer ‘with doors and keys, of course’.[3] A very limited number of persons have used, or are aware of instances of, a means of locking a church door without a key. Scrutiny of some older doorways does, however, certainly reveal evidence in the jambs of what might be termed ‘wooden sliding cross bar security systems’, or briefly, ‘bar locks’ (Figure 1.1). In the British Isles, as far as the present author originally believed, no attempt had been made to fully describe the function, distribution, or use and implications of this means of security. In the earliest years of the second millennium the present author identified and recognised the importance of bar locks which he had observed in Wales for the first time. At that time, bar locks, had been recently reported in churches in Southern Sweden and described in the PhD thesis of Dr Raine Borg.[4] Possibly without intention, Dr Borg intimated, in correspondence, that this occurrence was the first to be recorded in Europe. More recently, the present author was to discover the large amount of study undertaken in recent years on the subject of the defence of churches and like buildings.[5] An earlier study in France also refers to the defensive aspects of large churches.[6]

Church Security

In past times, just as today, it has always been necessary for buildings to provide security. This has been sought in order to protect various possessions, and to offer personal refuge and safety within the building. Before the invention of the locking devices with which we are familiar today, and in particular, the innovation of keys, the requirement must have created major and significant problems. For those with money and power, the ultimate protective structure in the past was provided by the sanctuary of the castle. At that time, in contrast to the castle, the early churches and the smaller monastic properties of the period were established to provide religious services and leadership, as well as the facility for personal private prayer. These were offered by invitation, and as today, they were dependent upon the buildings involved being open for attendance. Unless permanently supervised and controlled, the churches and their valuable contents could have, therefore, been subject to substantial damage and possible loss.

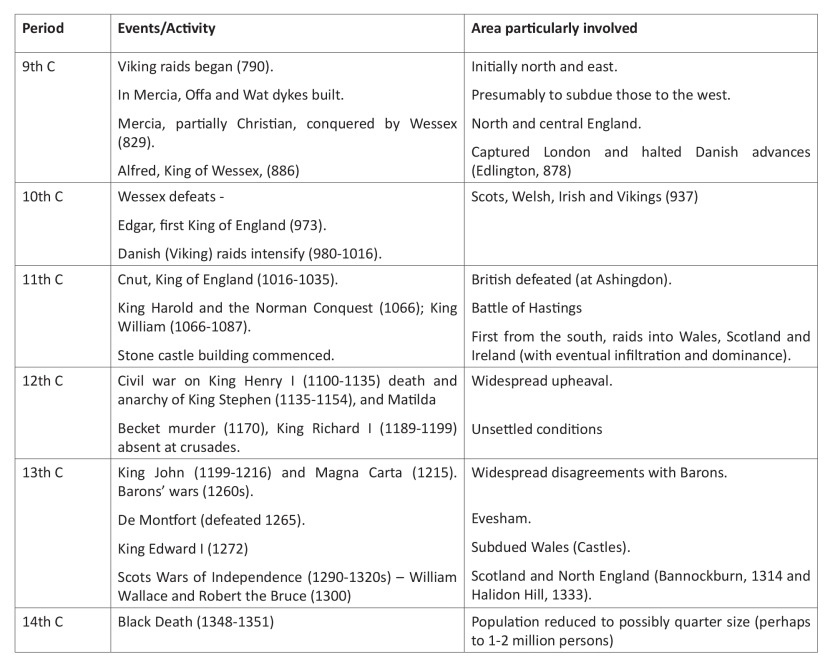

The historical records disclose that Viking, Norse and Danish marauding visitors found churches especially, relatively easy picking. Some of these raids have been documented by the current author and certain periods of Viking and Danish activity are referred to in Table 1.1 of the present work.[7] These particular accounts highlight the need for church security in fraught circumstances, but it is easy to imagine the routine need for church security in much less difficult ‘everyday’ circumstances, both in earlier and later periods. At the simplest level there would be a need to keep undesirables, animals and the weather out of churches. (The special circumstances of the churches in the Border country between England and Scotland in the early medieval period are examined below).

The relatively recent recognition that some early churches, in the absence of keys, were kept secure from the inside of the church, by means of thick wooden bars (bar locks), confirms the requirement that often permanent occupation by a person or persons must have become a necessity. Only from within the church was the positioning of bar locks possible.

The capability to lock a strong church door from the inside would have been the first fundamental step in securing the building and possibly providing some sanctuary for temporary occupants who had fled from their more fragile dwellings. The shuttering and provision of bar locks for windows is analogous. Instances are evident where the original church may have needed supplementary structural protection beyond that provided by the installed door bar locks, and these measures could have major implications for structural change and design in the buildings. These supplementary protective requirements and methods for achieving them are many and various and are considered below. The recognition of the role of bar locks in securing churches led the present author to consider the further measures introduced to enhance church security, but the starting point of this study is an examination of the evidence for bar locks which takes up the first half of this work. The more varied measures taken to enhance more general church security provide the basis for the second half of this work.

What is a bar lock?

Typically constructed of metal such as iron or steel, a modern bar lock might be described as a long bolt which may be attached to the inside or outside of a door, so that the shaft of the bolt may be slid into a housing either built into, or attached to, the door jamb on the opposite side of the door to the door’s hinge. Commonly, in current modern systems, the bolt may be additionally secured, or prevented from further movement, by some form of locking system involving a key. An enormous range of modern bar locks exists and modified forms of this type of security range from the standard ‘push-bar’ emergency exit, to other instances of longer bars across a full door width, such as where a central key withdraws a catch from the housings on both door jambs.

If security is required only from one side, as in the home, it is more common to separate the mechanical functions of the bolt from those of the lock and key. Simple effective door bolts may be applied manually. Outside the scope of this discussion there are the many non-mechanical means of modern origin (such as electronic and electrical methods), which can provide safe-keeping.

The term ‘draw bar’ has been used by certain authors as an alternative term for bar lock, placing the emphasis on the unlocking rather than the locking process.[8]

Keys and locks

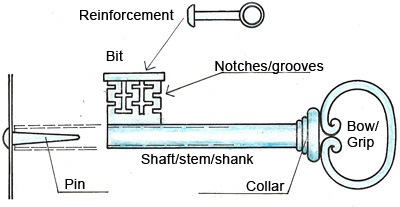

The security of buildings today may be optimised both inside and outside by using a locking system which typically involves one or more keys. For a single key to access both sides of a door locking system, a key-hole is necessary. The simplicity of this form of security poses the question as to how long locks and keys have been available, and in particular, for how long have they been used in churches? Both locks and keys vary enormously in their structure. Raine Borg has defined keys as being instruments that are programmed or coded through the shape of the bit, which matches the pins and wards of the lock (See Figure 1.2). The turning of the key typically closes or opens the lock. The bit is that part of the key which acts directly on the locking mechanism.

It is possible that the earliest locks and keys were constructed five or six thousand years ago and wooden keys and locks are recorded from ancient Egypt. Such a wooden device was recorded in Assyria in the city of Nineveh at the palace of Khorsabad (in Iraqi, Kurdistan) and said to date from 704BC.[9] It is probable that originally gravity-controlled pins fell into position to control the movement of a security bolt. The bolt was then freed by inserting a large and cumbersome wooden key which was used to manually lift and free the pins. The ancient Greeks may have invented and certainly used the keyhole and metal (typically bronze or iron) locks and keys. Homer’s Odyssey (Book 21) recounts how Penelope, wife of Odysseus, ‘… quickly undid the thong attached to the hook, passed the key through the hole, and with an accurate thrust shot back the bolt.’ Elsewhere, Penelope is said to use a ‘well-made bronze key with an ivory handle’ and the ‘bolting and barring’ of the courtyard gate is requested. Metallic bronze and iron keys were widely used by the Romans. Raine Borg suggests that the Romans could manufacture sufficiently suitable iron to create springs to enable padlocks to be created. The craft indeed was so sophisticated to allow the creation of somewhat similar so-called small ‘puzzle padlocks’ bearing a face or ‘mask’ in Celtic style. The padlocks were designed to secure small bags or money pouches and their distribution extended across Europe.[10]

Keys are collected widely but dating them and determining where, or for what purpose, they were used is difficult to ascertain. A useful ‘lexicon of locks and keys’ can be found on the web site http://www.historicallocks.com/en/site/h/historicallocks/dictionary/. This site gives details of the many varied locks and keys which may be found and their possible functions. Figure 1.3, again from a sketch by Raine Borg, illustrates several iron keys with claws, each long key, used to manually release different locking systems. They were probably of Viking (Celtic) age and were found in the Vӓrnamo area of Sweden. They were in all probability used in much the same manner as described by Homer.

Figure 1.4 illustrates a bronze key identified as of Viking source with a clawed blade (Historia om nycklar 3 liten) which is believed to have been used about AD 300; while Figure 1.5, which is a similar clawed key, has been described as of Anglo-Viking origin and dated to about AD 900 (author J. F. Smith). Dr Raine Borg holds a large personal collection of keys, and he has produced a drawing of one of his keys from southern Sweden which is thought to date from the early 1100s. It is believed to have been operated as a metallic (iron) mechanism within a block of wood and, as the key is more than 150mm long, it is possible to presume that locking could be achieved from either side (of a door) by means of a keyhole. In many locking mechanisms little of the action can be readily viewed and the workings may be encased. The pull-ring lock from Sweden (shown in Figure 1.6) required two hands to operate, one for pulling the ring whilst the other turned the key. It is dated to 1312-13 and is photographed here by Raine Borg.

Early Bar Locks

Figure 1.1, taken from the above-mentioned web site, shows the very simplest of bar locking systems created in timber. It has no key. Critically, it would protect only those people or objects on the side of the door bar lock. Such a locking system has not been observed by the present author in an ecclesiastical site. However, on occasions somewhat modified examples exist. Typically they are strengthened with metal parts and padlocks, to be used on rarely-used doorways in small churches, in order to secure the building. Such an example may be observed at Stragglethorpe church (SK 913 524), in Lincolnshire (Figure 1.7). The door illustrated must be of relatively modern construction. In other churches, bar locks of no great age and without supportive padlocks may provide security to a minor entrance, where the church has keys with locks to control principal entrances to the building.

There is ample evidence that bar locking systems were used in many churches of much greater age. In the oldest examples it is possible to attribute their origin to the Anglo-Saxon period. Typically, thick wooden doors were barricaded by an interior bar locking system. This amounted to a long, bulky length of solid wood about 0.08 to 0.12m in cross section, which ran across the back of the door and was held in position by a hole in the wall on either side of the door. On occasions there were two bars of this nature, one towards the top of the door, the other towards the bottom. This (or these) left the door immovable between the door rebate and the bar. To open the door the bar was slid into a cavity in the wall which was deep enough to accommodate the full length of the bar. The cross bars were typically at least 1.5m long, more than sufficient to cover the full width of the doorway aperture. Full evidence of the door (or the cross bar) involved is observed only rarely in the British Isles, but it is possible that, for ease of use, the weight of the bar was supported by appropriate attachments on the back of the door.

In his studies in Southern Sweden, Borg discovered three instances where remains of the cross bar were still present (all in Gotland County), and in all, 16 instances of churches with cross bar holes or ‘grooves’.[11] Twelve of these were in Gotland County. In many examples in Southern Sweden, two, three or even four doorways (but generally all the doorways in an individual church) carried evidence of cross-bar locking. The churches involved, were given building dates mainly within the early 13th C., but in the range of 1086 (Lӓrbro, Gotland) to 1400 (Sjösås, Kronoberg County). Dr Borg has advised that the work is to be published in the http://www.historicallocks.com web site (of which he is the author).

In the British Isles, with the invention of simple, cheap and effective mechanical key locking systems, the bar locks tended to fall into disuse and the holes for the bars were often filled and forgotten. In many instances the presence of a bar lock hole is difficult to ascertain for it may have been infilled with stone or wood when it was no longer required. It must be accepted that if all entry points to a church possessed a bar locking system those persons involved in locking the church (or other building) would have to remain inside the premises.

In the majority of churches where bar locking systems of the type just described occur, it is evident that the buildings were secured, therefore, for the defence of both people and property. This involved both the clergy and, if necessary, local inhabitants. According to the number of doors, each door would have been similarly protected in times of potential danger or need for security. It is clear that those involved in security by this means remained within the church until any imminent danger had disappeared. Occasionally these bars would have been of such a size and weight as to require more than one person to be able easily to fit them into position, rather than individuals.

What regrettably cannot be determined is the date from which each church acquired a key locking system to permit both exit and entry. That keys were readily available to the wealthy is clear from carvings on gravestones, typically those dated to about the 15th C. Keys were certainly known much earlier but they were uncommon. King Henry VIII is known to have been accompanied always by a door key locking system which was fitted for his privacy, wherever his geographical locality. The British Museum holds three keys, described as padlock keys, tentatively dated to the period 9th to 11th C. Although they might possibly have been used in a church, they have not been related to any specific church by locality: neither has their precise function been suggested.

To purchase a printed copy, please follow this link.

References

Bonde, S. 1994. Fortress-Churches of Languedoc. Architecture, religion and conflict in the High Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Borg, R. 2002. Smålands medeltida dopfuntar. En inventering i komparativ belysning. (Medieval Baptismal Fonts in the Swedish province of Smolandica. An inventory in the light of comparison). Göteborg University: Gothenborg Studies in Art and Architecture, 11, 281 pp., Göteborg, Vols I-II.

Brooke, C.J. 2000. Safe Sanctuaries: security and defence in Anglo-Scottish Border Churches 1290 – 1690. John Donald, Edinburgh.

De Vries, M.J., Cross, N. and Grant, D.P. (eds), 1992. Design Methodology and Relationships with Science: introduction. Kluwer Academic, Eindhoven.

Harrison, P. 2004. Castles of God: fortified religious buildings of the World. Boydell Press, Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Potter, J.F. 2005b. No stone unturned – a re-assessment of Anglo-Saxon long-and-short quoins and associated structures. Archaeological Journal, 162, 177-214.

Potter, J.F. 2005c. Field Meeting: Romney Marsh – its churches and geology, 22 May 2004. Proceedings of the Geologists’Association, 116, 161-175.

Potter, J.F. 2009c. Patterns in Stonework: The early church in Britain and Ireland; an introduction to ecclesiastical geology. British Archaeological Report, British Series 496, xxvi + 191pp., Archaeopress, Oxford.

Potter, J.F. 2013a. Searching for Early Welsh Churches: a study in ecclesiastical geology. British Archaeological Report, British Series 578, xxxvi + 457pp., Archaeopress, Oxford.

Potter, J.F. 2015. Patterns in Stonework: The Early Churches in Northern England: a further study in ecclesiastical geology. Part A. The Counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, Derbyshire, Durham, Lancashire and Lincolnshire. British Archaeological Report, British Series 617, xxxvii + 314pp, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Potter, J.F. 2016b. Patterns in Stonework: The Early Churches in Northern England: a further study in ecclesiastical geology. Part B. The Counties of Northumberland, Nottinghamshire, Staffordshire, Westmorland and Yorkshire. British Archaeological Report, British Series 624, xxxvi + 234pp.

Manning, C. 2010. Patterns in stonework: The early church in Britain and Ireland; an introduction to ecclesiastical geology. British Archaeological Report, British Series 496. Book Review, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Dublin. (And associated correspondence).

Slocum, J. and Sonneveld, D. 2017. Romano-Celtic Puzzle Padlocks: a study in their design, technology and security. Archaeopress, Oxford.

[1] Potter 2005b, 2009c, 2013a, 2015, 2016b

[2] Harrison 2004

[3] Manning 2010

[4] Borg 2002

[5] Brooke 2000

[6] Bonde 1994

[7] Potter 2009c

[8] Brooke 2000

[9] De Vries et al. 1992

[10] Slocum and Sonneveld 2017

[11] Borg 2002

Awesome story about Security reasons

LikeLike