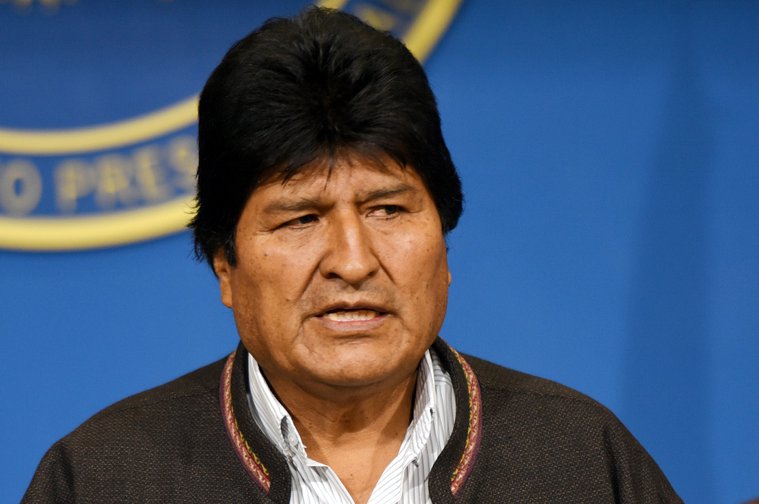

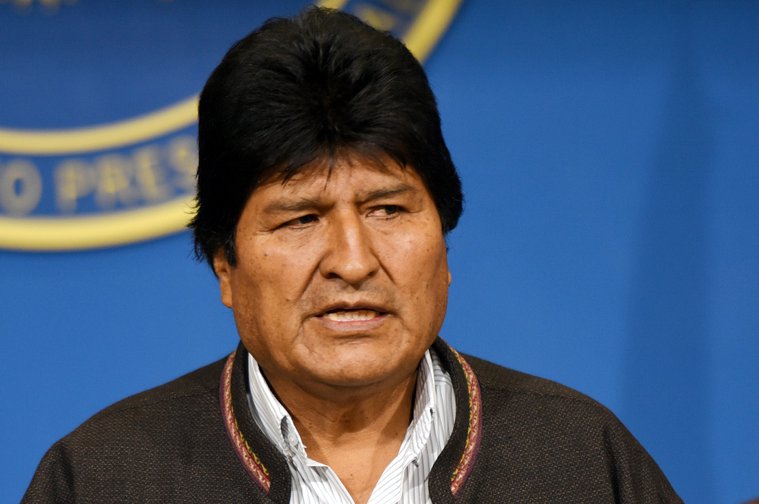

Evo Morales: the fall of the hero of the Bolivian transformation

The resignation of Bolivian president Evo Morales brings to an end an incredible era in Bolivia’s history. Morales, a one-time coca farmer, and the first indigenous president of the country, came to power on a wave of popular protest and sophisticated grassroots mobilisation. His government slashed poverty and inequality and raised the living standards of millions of people. Had these achievements taken place in a country advised by the World Bank and IMF, rather than one implacably opposed to the neoliberal doctrine of those institutions, Bolivia today would be hailed as a development miracle.

At the same time, Morales made serious mistakes; in particular, the focus of power around his own personality and his accommodation with some of Bolivia’s elite interests. That means that while Bolivia today is immensely better off than it was in 2005, before Morales’ first victory, it is also highly unstable, gripped by a political crisis that could have been avoided.

Fighting poverty

Evo Morales took office in January 2006. He was elected on the back of some of the most inspiring mobilisations against corporate globalisation, in particular the famous ‘water wars’ through which corporate giant Bechtel was kicked out of Bolivia after a disastrous privatisation of the water system in the city of Cochabamba in the year 2000.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Morales was the first president who came from Bolivia’s large indigenous minority and one of the first not to represent Bolivia’s tiny elite. His election by itself made large parts of Bolivia feel enfranchised for the first time. With a strong movement behind him, and many of the movement’s leaders given roles in government, he set to work transforming Latin America’s poorest country. He was helped by the other ‘pink tide’ leaders who were sweeping the continent, including Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, Néstor Kirchner in Argentina and Luiz ‘Lula’ da Silva in Brazil.

Even by the standards of Latin America in the 2000s, Bolivia’s achievements were impressive. The country’s economy has grown at a steady 4.9% per year – an incredible enough figure for a country used to high indebtedness and dependent on foreign loans. Real per capita GDP grew by more than 50% over 13 years, twice the rate of growth for the Latin American and Caribbean region, and today Bolivia still boasts the highest growth of per capita GDP in South America.

But growth often says little about human development, and can regularly go hand in hand with rising inequality, and even rising poverty. In Bolivia, thanks to Morales’ other policies, things were different, and the benefits of growth were felt by the poorest. Poverty fell from 60% in 2006 to 35% in 2017. Extreme poverty more than halved - from 38% to 15%.

This was achieved by both massive public investment and redistribution of wealth. Bolivia’s unemployment nearly halved (7.7% to 4.4%) by 2008, and this didn’t change much even after the global financial crisis of 2008. Moreover, the minimum monthly wage increased threefold. Huge changes were made to the education system, bringing many more people into full-time education. Social transfer payments were given to millions of poorer Bolivians, especially to the young, helping keep kids in schools, and giving dignity to the elderly.

Transforming the economy

Had other governments achieved such incredible economic success, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund would be shouting about it from the rooftops. Except that Morales recognised the disastrous role that both institutions had played in Bolivia’s history. Far from following their advice, he declared independence from these engines of debt, austerity and structural adjustment and refused a new loan agreement.

Instead of following the ‘logic of the market’, Morales paid for his programme with a combination of nationalisation and public ownership, taxation of big business and a focus on internal debt linked to high levels of national investment. This included a programme of ‘de-dollarisation’ to break the dependence of Bolivia’s economy on imported dollars, something that had previously removed the government’s ability to use monetary policy to benefit Bolivians rather than international capital.

Almost all these policies were anathema to the Bank and the IMF. In fact, US think tank CEPR investigated IMF advice to Bolivia. It found that the institution has lauded the failing policies of the previous government – though they were perplexed that “a country perceived as having one of the best structural reform records in Latin America experienced sluggish per capita growth, and made virtually no progress in reducing income-based poverty measures.” Never one to learn from their mistakes, the IMF strongly opposed the policies Morales was about to implement, expressing “opposition to any kind of nationalisation or even lesser attempts at increasing government control over hydrocarbon resources”, a key policy instrument for Morales.

Poverty fell from 60% in 2006 to 35% in 2017.

In fact, in 2007, Morales announced that he was withdrawing from the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), an arbitration system which allows foreign investors to use investment deals to sue governments for treating them ‘unfairly’. Bolivia had already been repeatedly targeted by this ‘corporate court’ system, including by Bechtel who took action against Bolivia after the privatisation of the Cochabamba water system was reversed. Bechtel’s $50 million claim against the country went far beyond the investment they’d made in the country, and was massively inflated for estimated lost future profits, common practice in such arbitration claims.

Morales saw that these corporate courts would be a major threat to his plans to control the hydrocarbon multinationals and use the wealth to benefit his people. Bolivia therefore became the first country in the world to withdraw from ICSID.

Morales saw, along with other leaders of the ‘pink tide’, that a country like Bolivia simply could not be transformed under the neoliberal laws of the global economy, which would simply continue to suck wealth out of the land and people of poorer countries. Neither was a single nation state sufficient to take on the whole global economy itself. Only by creating new institutions which put the right of Latin Americans ahead of those of the privileges of international capital, could countries like Bolivia truly develop. Bolivia played a key role in building alternative trade area, an alternative currency, and a public bank, and though these institutions often remained underdeveloped, they created the most serious alternatives to neoliberal global integration in the last 40 years.

The mistakes

Despite these achievements, the Morales’ government did make real mistakes – and the mistakes got worse as time went by. Morales’ own constitution, an amazing document, prohibited a president for standing for more than two terms. In 2014 he argued that his first term didn’t count as one of those terms because it preceded the constitution. This year he ran for a fourth term, after a supportive constitutional court allowed him to scrap presidential term limits – a case he only took after losing a referendum he called to scrap term limits.

Pablo Solon, former colleague of Morales, and his ambassador to the UN, believes that these problems began early on, with well-intentioned but mistaken co-option of social movement leaders into Morales’ party and government, later becoming ever more personality-focussed and less able to tolerate criticism. The claims of electoral irregularity in the recent election, however deep it really goes, suggests an increased disinterest in democratic accountability. Head of the Democracy Centre, Jim Schultz, whose left-wing NGO was targeted by Morales’ government, is a strong critic of the closing down of democratic space in Bolivia. Writing of the recent election, he says that the claim that’s what’s happening in Bolivia is simply a ‘coup’ or a story of ‘empire vs radical government’ is far too simplistic, and doesn’t help those who really want to build a different sort of society. In fact, he says it’s downright dangerous: “This is how civil war begins.”

But the declining commitment to democracy created a deeper problem – an increasing lack of real radicalism in Morales’ economic programme. As Pablo Solon says of Morales’:

“Once he had obtained an absolute majority [in Congress], he did not deepen the original program that we had, but instead sought out pacts with sectors of the opposition, based on serious concessions, and in particular with the agribusiness sector of the eastern lowlands, which had sabotaged his government during the first term. These concessions included everything from allowing genetically modified organisms to promoting biofuels, promoting the export of meat, and not following through on the regulation of the social-economic functions of medium-sized landholdings and business-scale landholdings, which allowed large landowners to preserve their ownership of land.”

He saw the necessity of breaking with the neoliberal institutions and building a different form of integration with his fellow ‘pink tide’ presidents in Latin America.

While the recent Amazon fires in Brazil were well reported on, with many rightly pointing to the specific role of fascist leader Bolsonaro, few journalists pointed out that similar fires were raging in Bolivia. While Morales strongly acknowledges climate change as a threat to humanity, his increasing closeness to agribusiness has seen him introduce policies directly linked to devastating deforestation.

While exports of hydrocarbons, minerals and agricultural products, if proper regulated and taxed, can play a role in the development of a country like Bolivia, the size and over dependence on these sectors is now hindering the democratisation and diversification of the economy, and pushing the government into conflict with groups – like the indigenous poor – who should be its core constituency. A recent 70-year contract to export Lithium to Germany met mass protests when locals discovered how low the royalty payments would be.

The current political crisis has absolutely been exploited by the right-wing in Bolivia, as well as right-wing leaders including Trump and Bolsonaro across the Americas. And what comes next in Bolivia is almost certain to be very much worse than Morales. But none of this means the government should be ‘let off the hook’ for its mistakes. The crisis has been coming for a long time, and it could have been avoided with different policies.

Where to look for hope? As an emboldened right-wing has re-emerged across Latin America, so a new wave of grassroots groups and street protests has risen to oppose these neoliberal and fascistic leaders. The massive mobilisations in Chile are the most obvious manifestation of this movement, but the defeat of Macri in Argentina’s recent election and the large scale social movement resistance to Bolsonaro in Brazil also give us plenty of hope too, as does the still powerful indigenous movement in Bolivia. That hope doesn’t start with governments, but with the strength and independence of the movement – which is what gave power to the ‘pink tide’ in the first place. As Pablo Solon comments “We have to build and rebuild something different, and learn from our mistakes.”

We should never forget the substantial successes of Morales’ governments. In just under 15 years in power, he achieved far more than most countries manage, precisely because he saw the necessity of breaking with the neoliberal institutions and building a different form of integration with his fellow ‘pink tide’ presidents in Latin America.

But as the period of optimism in these governments fades, and social movements return to the streets to take on right-wing governments all over again, let’s remember Morales’ mistakes too. Failure to do so will not help us to build something better and stronger.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.