The Artist

By Txomin Badiola

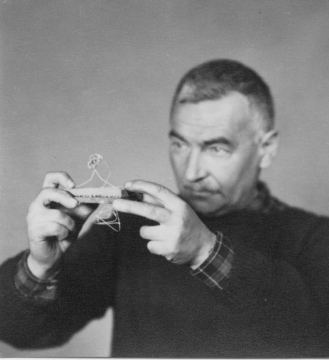

Jorge Oteiza (Orio 1908- San Sebastián 2003), is one of the most important Basque artists in Spanish 20th-century Art, as well as one of the most influential. The impact of his work in its various (plastic or theoretical) facets can be seen, from the 1950s to the present time, in disciplines such as sculpture, painting, architecture, poetry, aesthetics, cinema, anthropology, education or politics. Oteiza’s life and work were always shrouded in a mythical aura owing to his visionary troubled character, especially due to the fact that in 1959, Oteiza was to announce unexpectedly that he was abandoning sculpture; an announcement that was even more astonishing if we bear in mind that at that time he was at the height of his artistic career and had recently been awarded first prize for Sculpture at the Sao Paulo Biennial in 1958, with exhibitions at various galleries in America, and contracts to display work in Germany and other countries. Nonetheless, if we bear in mind his personal idiosyncrasies and intricate aesthetic theories, this decision might not seem so shocking. Right from the very start Oteiza had claimed that he wanted to become the sculptor he wasn’t, and as a result, his entire career was merely a rejection of himself and an appeal to who he wanted to be, a radical questioning and permanent reconstruction of subjectivity itself, based on the idea that the final purpose of art is not the work, painting or sculpture, but the formation of the artist himself as someone trained through art and ready to act directly on society. A self-taught artist, Oteiza began making sculptures that fell within the field of the kind of expressionism or primitivism that was begun by Gaugin, Picasso or Derain, and developed through Brancusi, Epstein and others. After a long stay in South America, the sculptor gradually developed the theoretical and practical fundamentals of his aesthetic, and the “natural” sculptor that he had inside himself, took the steps he needed to become the artist that to a certain extent was in control of his mechanisms and tools. This intellectual adventure was to be reflected in texts like the Letter to the Artists of America or The aesthetic interpretation of American megalithic statues.

Jorge Oteiza (Orio 1908- San Sebastián 2003), is one of the most important Basque artists in Spanish 20th-century Art, as well as one of the most influential. The impact of his work in its various (plastic or theoretical) facets can be seen, from the 1950s to the present time, in disciplines such as sculpture, painting, architecture, poetry, aesthetics, cinema, anthropology, education or politics. Oteiza’s life and work were always shrouded in a mythical aura owing to his visionary troubled character, especially due to the fact that in 1959, Oteiza was to announce unexpectedly that he was abandoning sculpture; an announcement that was even more astonishing if we bear in mind that at that time he was at the height of his artistic career and had recently been awarded first prize for Sculpture at the Sao Paulo Biennial in 1958, with exhibitions at various galleries in America, and contracts to display work in Germany and other countries. Nonetheless, if we bear in mind his personal idiosyncrasies and intricate aesthetic theories, this decision might not seem so shocking. Right from the very start Oteiza had claimed that he wanted to become the sculptor he wasn’t, and as a result, his entire career was merely a rejection of himself and an appeal to who he wanted to be, a radical questioning and permanent reconstruction of subjectivity itself, based on the idea that the final purpose of art is not the work, painting or sculpture, but the formation of the artist himself as someone trained through art and ready to act directly on society. A self-taught artist, Oteiza began making sculptures that fell within the field of the kind of expressionism or primitivism that was begun by Gaugin, Picasso or Derain, and developed through Brancusi, Epstein and others. After a long stay in South America, the sculptor gradually developed the theoretical and practical fundamentals of his aesthetic, and the “natural” sculptor that he had inside himself, took the steps he needed to become the artist that to a certain extent was in control of his mechanisms and tools. This intellectual adventure was to be reflected in texts like the Letter to the Artists of America or The aesthetic interpretation of American megalithic statues.

In the late 1940s he came back to Spain. The huge monolithic sculpture that Oteiza naturally identified with underwent a dematerialisation process according to which the statue-mass had to make way for the “trans-statue” or energy-statue of the future: an artefact that basically consisted of space and energy. Oteiza, who was always attentive to developments in science, would compare this transformation of mass into energy with the one carried out by nuclear research. The ideas of nuclear fission and fusion would allow him to rule out options, and as a result, as against the idea of “fission” or shattering of a heavy mass that would be exemplified by Henry Moore’s perforated sculpture (whose work had a profound impact on him in the 1940s), Oteiza proposed a type of sculpture that would be able to release energy through the “fusion” or coupling of light units. One of the definitive sculptures in this new type of approach was sent by Oteiza, as the only Spanish representative, to the International Competition for the Monument to the Unknown Political Prisoner held in London in 1952.

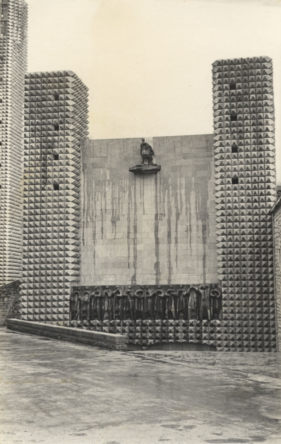

While he was deeply involved in abstract research in the early 1950s, Oteiza accepted the job of producing the statues for the new Basilica in Arantzazu. This project gave Oteiza the opportunity to link this notion of a new aesthetic spirituality rooted in modern art with popular religious feeling, and to do this he abandoned one form of strictly abstract expression for another, that even though it included the spatial innovations of the trans-statue, would be able to reach out to a group for whom figurative references were vital. Despite this, the statues that Oteiza began in 1952, were banned by the church in 1954, and couldn’t be finished until 1969.

Arantzazu

Once his project for Arantzazu had been banned, the sculptor once again took up his Experimental proposition and brought it to fruition, which was precisely based on defining and structuring these open or lightweight units so that they can be activated in space through extensive use of emptiness and negativity, and by subduing their expressive elements through receptiveness and stillness. This process, developed from hundreds of small models in very basic materials that would form what was known as the Experimental Laboratory, was to produce sculptures made in stone and structures made from fine sheets of metal arranged in “experimental families”: Emptying the sphere, Opening polyhedrons, Empty Structures, Empty Boxes, etc. Implicit to the actual internal logic of this process of dematerialisation and silencing of sculpture was the need for an end to this process; something that Oteiza devised in the form of experimental conclusions. These were minimal, empty sculptures produced in 1958-59, in which some people, like the sculptor Richard Serra, thought they saw a precedent for Minimalism.

Once his project for Arantzazu had been banned, the sculptor once again took up his Experimental proposition and brought it to fruition, which was precisely based on defining and structuring these open or lightweight units so that they can be activated in space through extensive use of emptiness and negativity, and by subduing their expressive elements through receptiveness and stillness. This process, developed from hundreds of small models in very basic materials that would form what was known as the Experimental Laboratory, was to produce sculptures made in stone and structures made from fine sheets of metal arranged in “experimental families”: Emptying the sphere, Opening polyhedrons, Empty Structures, Empty Boxes, etc. Implicit to the actual internal logic of this process of dematerialisation and silencing of sculpture was the need for an end to this process; something that Oteiza devised in the form of experimental conclusions. These were minimal, empty sculptures produced in 1958-59, in which some people, like the sculptor Richard Serra, thought they saw a precedent for Minimalism.

Finally, faced with the Nothingness formed by these conclusions, Oteiza had to face up to an ethical question: Once an experimental process was over, should the artist continue to painstakingly stick to his own form of expression, or should he switch to another stage, abandon his professional activity and embrace new methods of creative intervention in society? Oteiza answered his own question, convinced that the definitive meaning of art lay outside art itself: “If the contemporary artist doesn’t expire in art, the man with a new existential sensibility cannot be born and the politically new man cannot begin”. Silence, the result of a language based on absence and emptiness, must end in a lack or a void of language. After abandoning sculpture, Oteiza was to publish his book Quosque Tanden! in 1963. This was a text that sums up many of the theoretical concerns that had accompanied him throughout his life and career since the 1930s, and formed the basic reference book for the Basque political and cultural intelligentsia of the time. Later on, he wrote Spiritual exercises in a Tunnel, which was banned by Franco’s censors, and wasn’t published until the 1980s, although it was widely circulated in a photocopied version. At the same time he began his experiments in the field of cinema with the film project Acteón for the production company, X-films, although it was finally made by another director in a totally different version to the one conceived by Oteiza. He also began various projects such as the one he sent to Malraux for an Institute of Aesthetic Research in the French Basque Country, a pilot children’s university for Elorrio, a Basque Aesthetic Anthropology Museum project for Vitoria, an art gallery project as a production company, a project to integrate the avant-garde into traditional forms of expression, the Basque School and Deva School groups, etc. Most of these projects were resounding failures and the ones that did get launched were never up to Oteiza’s expectations.

Between 1972 and 1974, Oteiza decided to finish off some of the series that had been left unfinished when he gave up sculpture and he produced his Chalk Laboratory. Some of his results, together with new versions of models of previous sculptures, were exhibited in1974 in the Txantxangorri Gallery in Fuenterrabía. In the late 1970s he moved from Irún, where he had been living since 1958, to Alzuza in Navarre, where he continued his theoretical activity while at the same time he once again devoted himself tirelessly to his poetry, which he had begun in the period of the Arantzazu project with Androcanto y sigo. Ballet for the stones of the apostles on the road, and was to continue with books like God Exists to the Northwest or Itziar: Elegy and other poems. Oteiza’s multifaceted aims, combined with the fact that his projects often came to nothing, created the media image of a figure who was in a state of permanent resentment and keen to vent his rage on anyone who crossed his path, which he did especially viciously whenever this was a politician. This image helped decisively to create the “Oteiza myth”, to the extent that it considerably overshadowed his sculpture. In 1988 the Caixa Foundation organised the first anthological Oteiza exhibition, Experimental Proposition, in Madrid, Bilbao & Barcelona, which put his sculpture in the headlines, and he was invited to the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennial with its subsequent international impact. During this period he received several awards including the Fine Arts Medal or the Prince of Asturias of the Arts award. In 1996 Oteiza and the Government of Navarre ratified the agreement on his work being placed in the Oteiza Museum Foundation. On the 9th of April 2003 Oteiza died in San Sebastián. Several exhibitions of his work were held that culminated in the one organised by the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and at its headquarters, the one at the Frank Lloyd Wright building on 5th Avenue in New York, and at the Queen Sofia Museum in Madrid. In 2007 his work was included at Documenta XII in Kassel as an essential benchmark in any attempt to answer the question Is Modernity our Antiquity? Over the last few years the Jorge Oteiza Museum Foundation has brought out some critical re-editions of his most important works as well as exhibitions and publications that investigate specific aspects of his sculpture: the Sao Paulo Biennial in 1957, the Chapel for the Road to Santiago, the Experimental Laboratory, etc.

Jorge Oteiza