Before and Beyond Bitcoin Part three, Lessons from Weimar Germany's hyperinflation

What can interwar Germany, 1920s hyperinflation and the rise of the Nazi party tell us about Bitcoin?

Quick Take

Guided by Austrian economists, some Bitcoiners think there is quite a lot of value in resurrecting Germany's 1920s experience of extreme inflation – the so-called “Dying of Money” – as both an apocryphal warning of the dangers of fiat currency (including the rise of Hitler and the Second World War) and a motivation to hold BTC as a store of value.

Here I revisit the economic history of the Weimar republic and conclude the following.

- Interwar Germany does not provide an accurate model for the US in the 2020s. The main cause of Weimar hyperinflation was an unprecedented debt burden denominated in hard money forced onto a recalcitrant German government. An unruly economic elite left hyperinflation of the currency as the only alternative for a precarious republic. Hyperinflation was a political rather than an economic problem.

- Bitcoin would have likely acted as a stable store of value in 1923, but so did every other hard asset, including common stocks.

- The rise of Nazism was not associated with fiat money printing in the 1920s, but was actually caused by rising austerity and other hard money policies in the 1930s. Having BTC as the reserve asset would have likely exacerbated the deflationary forces that have been shown to have directly influenced the fall of the republic, the rise of the Third Reich and the Second World War.

- Deflation, rather than hyperinflation, contributed to the rise of Nazi Germany.

- Certain monetarists and most (all?) Keynesians agree that central bank policies currently in practice and currently despised by monetarist (!) and Austrian economists as well as Bitcoin maximalists would have likely altered the course of the Great Depression, and perhaps even stopped the rise of European populism.

- Bitcoin may solve many monetary and economic problems, but BTC would not have prevented the Great Depression, and likely would have worsened it. Governments need other tools besides hard money.

Introduction

It somehow seems so convincing, especially when well-known goldbugs, Bitcoin maximalists, Austrian School economic pundits and famous ‘Big Short’ hedge fund managers (see Michael Burry's tweet below) repeat and retweet it: Governments can’t help themselves and will eventually print so much money that hyperinflation – a catastrophic erosion of the value of their own fiat currency – will be the inevitable result.

The narrative is especially relevant today, as supposedly "big" inflation is coming: Unprecedented “money printer go brr” Fed policies risk USD hyperinflation. The short but catastrophic burst of hyperinflation that occurred in Germany’s Weimar Republic in 1923 has therefore captured the attention, and the memes, of a new generation of investor. Books popular with the von Mises Institute (see References) with names like “When Money Dies” have become required reading for BTC maximalists, as they always were with a certain style of anti-government skeptic Wall Street investor (e.g. “bond vigilantes”).

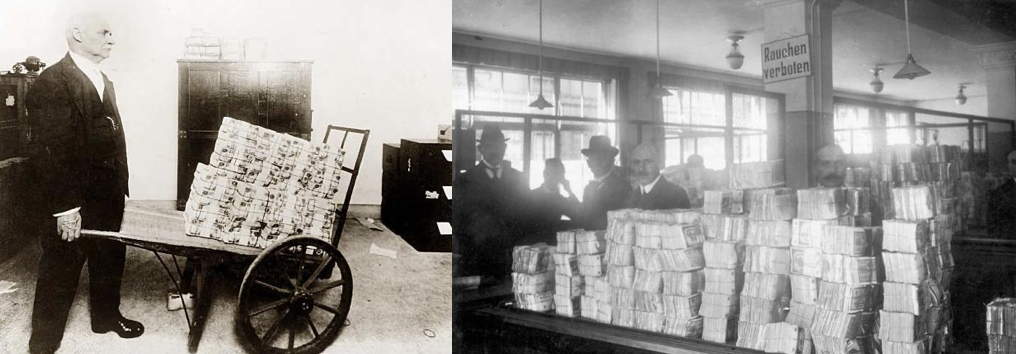

Inspired by Austrian School-based analysis, Bitcoiners are using “wheelbarrows full of cash” (see right) memes from the interwar years to market BTC as the only hedge against government failure to protect the purchasing power of the USD. In their opinion, not only is BTC an inflation-proof store of value, guaranteed to gain versus the USD, but adapting BTC as a reserve currency will prevent such hyperinflation and therefore other economic harms. In this view, besides destabilizing the financial and real economies of Germany by punishing holders of fiat and rewarding those with real assets, hyperinflation led directly to the rise of the Nazis, and, by extension, to the Second World War.

Bitcoiners therefore are interested in the Weimar hyperinflation story as it confirms the folly of an over-reliance on fiat currencies as a store of wealth as well as the dangers of not enacting inflexible “hard” monetary policies (such as inflation-resistant BTC, see right). The story also provides an urgent warning to move into a store of value such as BTC in anticipation of out-of-control inflation that must eventually result from the Fed’s highly dovish (expansionary) policies.

Based primarily on my undergraduate teaching of interwar German economic history at the University of Cambridge last year, I present here what has become the accepted account of interwar German monetary history, and consider what relevance it has for cryptocurrencies. Specifically, I use history to help answer the following two questions:

- Does the Weimar hyperinflationary experience offer any hints that hyperinflation is on the horizon in the 2020s United States?

- Would Bitcoin have prevented the 1930s Depression in Germany and possibly therefore the Second World War?

Here is the punch-line upfront. Economic historians generally agree that:

- German hyperinflation was caused for the most part – directly and indirectly – by Allied demands for post-War reparations denominated in hard (gold-denominated) money. This is hardly surprising. In many other cases in other countries, hyperinflation stemmed from a similar hard-currency problem (generally, the USD). As the US does not and is unlikely to have a destabilizing requirement to pay in “hard” currency (eg gold or BTC), Germany’s rather unique hyperinflationary experience cannot in any way be seen as a predictor of the USD’s fate.

- The rise of the Third Reich actually occurred during a prolonged period of deflation and fiscal austerity, problems that Bitcoin, being deflationary and fiscally limiting governments by its nature if used as the reserve currency, are more likely to cause than solve. History warns us that a reliance on hard money and without a credit backstop (e.g. central banks and banking) can end very badly for the global economy.

Bitcoin offers many benefits over other stores of wealth, as long as adoption continues apace. Certainly, BTC would have been an inflation-proof asset had it existed in Germany in 1923 and mirrored today’s popularity. Yet hyperinflation in the manner of Weimar Germany is unlikely to appear in the near future in the United States.

However, if anything, the economic troubles that preceded and perhaps even caused the Second World War are more likely to occur in the future should an inflation-proof asset become the dominant money.

The hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic

The speed and degree of destruction of the purchasing power of the German mark from 1921 to 1923 is unprecedented in developed economies. As result of annualized price level changes of 1,000,000s of times (see right), the real value of savings of many Germans was wiped out and a lot of debt, including Weimar republic obligations, was effectively not repaid. Those with useful and real assets, on the other hand, were inflation-proof.

Narratives of the effects of hyperinflation on the German citizenry of the 1920s, and the effects it may have had on the rise of the Nazis, have recently exited their obscurity from Austrian school (anti-Central bank) websites. Michael Burry quoted from When Money Dies, a book that used to be available for free on the von Mises Institute website:

All the marks that existed … were not enough to buy a tram ticket in 1923

In addition to the direct impacts of hyperinflation on the economy, some worry about its political effects. For example, there is a subset of laypeople and otherwise well-respected academics who believe that Weimar hyperinflation “elected Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor”.

Weimar Germany has therefore resurfaced as a cautionary tale, as the parallels between the latest US economic cycle and Germany in the 1920s, according to some, appear to be many:

It would not be an exaggeration to say that much of economic history has been contested and often revised. Interwar Germany is no exception. In my student supervisions, however, it is generally agreed that:

- The headline number of the gold-indexed reparations demanded by the Allies for losses during the Great War was staggering in size.

- Though Germany ended up paying significantly less, the debt and related Allied actions were unpopular, and de-legitimized any efforts to raise taxes to pay it. It has also been argued that the government itself may have damaged the economy in order to lower the reparations bill (see meme below).

- The fall in industrial output combined with non-compliant taxpayers forced Germany to borrow and print money, in a terrible feedback loop.

- Hyperinflation was extremely short lived and did not significantly impact unemployment. Stability followed quickly in early 1924.

Effectively, the 1922-1923 hyperinflation was, in the now accepted account, of political rather than economic causes (Ferguson 1995, 1996). Price stabilization could have occurred much earlier if it was so desired by the German interests.

The German monetary situation, "Golden Fetters" and the rise of the Nazis

The five stable years that followed the hyperinflation were ended by the Great Depression. The actual causes remain hotly contested, but there are a few points we mostly agree on.

- Deflation caused by the fall in industrial and agricultural input prices and the eventual mass failure of banking systems led to severe credit contraction and even more deflation (mostly agreed by Bernanke, Keynes, Friedman & Schwartz, etc).

- The gold standard (so-called “golden fetters”) and a focus on domestic policies allowed deflation to spread, and led to banking failures, output decreases and further deflation throughout the developed world (Eichengreen 1995).

- It was the Great Depression and not the hyperinflation that caused mass unemployment. The government’s policies of increasing income taxes and cutting government spending worsened the crisis. Germany’s exit from the gold standard in 1931 should have freed it up to pursue expansionist policies to counter deflationary pressures. Yet, Germany had an incentive to appear a basket case economy to the ex-Allies while renegotiating war reparations payments. By the time the Allies agreed to cancel the remaining payments, Hitler’s popularity was already on the rise.

- By 1933, ten years after the worst of the hyperinflation, and during a prolonged period of deflation, the Nazis came to power. In 1931, Hitler acknowledged that the austerity would “help my party to victory”. The evidence suggests a strong link between austerity and the rise of the Nazis. If the austerity would have been halted upon Germany’s exit from the gold standard, Hitler may not have dominated the elections of 1933.

Germany was not the only country to fail to enact expansionary policies during the early 1930s. Now discredited views of the gold standard and the need for the credit system to suffer through the deflation to “cleanse the system” were rampant among US politicians and even bankers. As a result, debt overhang and bank failures contributed to the massive deflationary pressures from rapid output declines (Bernanke 1995). Overall, it was a commitment to hard money and to austerity that prolonged the Great Depression.

The link between austerity and populism is an important one to identify. Only one in 25 Germans realize that the rise of Nazism occurred during rampant deflation, rather than hyperinflation.

Where does Bitcoin fit?

Bitcoin maximalists have taken Satoshi’s dream of censorship proof decentralized payments and pivoted more towards BTC’s anti-inflation properties: Bitcoin is a hedge against profligate government spending that will end with the demise of the US dollar’s purchasing power.

The Weimar hyperinflation history functions for Bitcoin’s best “shillers” as a sort of anti-tulip allegory. BTC should rise in price because it is supply-limited, while the US dollar is heading for a dramatic relative decline. Indeed, even less dogmatic investors can’t help but be scared by the money supply increases to record levels in the US. If it is true that USD is being “printed” so fast (see M2, below) that we will soon need wheelbarrows of cash to do our shopping as in 1923 Germany, then Bitcoin could increase many multiples from here.

Of course, like in Weimar Germany, other assets should in theory also rise as much as Bitcoin (or more, depending on perceived utility). But all that matters to maximalists is that BTC priced in dollars should “go to the moon”.

It is, however, hard to imagine the USD being subject to an annual external payment demand in metallic (non-USD) money equal to as much as 60% of all exports, as was Germany’s under the agreement from the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. It is equally unlikely that the US government would purposefully (and successfully) sabotage its own economy and leave it in ruins in order to avoid paying it. Finally, I see no possibility that the US chooses complete monetary collapse over the other possibilities (e.g. raising taxes and duties). To summarize, both the economic and the political differences between then and now are immense.

Now for the more controversial part of the question. Would the existence of BTC as a reserve asset have helped or hindered the German recovery of the early 1930s and therefore prevented the Hitler’s rise? It is difficult to see how Bitcoin as the German reserve asset could have saved the German economy, as a BTC-based economy would have experienced further deflationary pressures while preventing any deviations from the austerity that begat Hitler. Price stability is a bug and not a feature in the face of deflationary pressures.

The Great Depression, transmitting global deflation through the gold standard resulted in forced austerity in Germany, which in turn led to mass unemployment, which led directly to the rise of Nazism (Galofre-Vila et al 2021).

It is very likely that coordinated monetary policies in the Keynesian vein, as were practiced in 2008-10 and beginning in March 2020 could have prevented the Great Depression. As Crafts and Fearon conclude:

The big lesson that has been correctly identified [from the history of the Great Depression] is not to be passive in the face of large adverse financial shocks. Indeed, aggressive monetary and fiscal policies were immediately implemented to halt the financial disintegration. Fortunately, countries were not constrained by the oppressive stranglehold of the gold standard.

The Fed should have expended the money supply in 1930, and also supported other central banks. As Ben Bernanke (2002) stated in a speech honoring monetarist Milton Friedman who suggested that the Fed should have acted to increase the money supply in 1930 to halt the Depression,

I would like to say to Milton and Anna [Schwartz]: Regarding the Great Depression. You're right, we did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.

Conclusions

Could hyperinflation of the Weimar type occur in the 2020s? I think we can answer in the negative. An external debt shock of the kind experienced by Weimar Germany is extremely unlikely, while the deterioration of the USD to Zimbabwe levels is equally implausible. More importantly, perhaps, the unique political position of Germany in the 1920s prevented any non-inflationary responses.

Would BTC have been a store of value during the Weimar inflation? Yes, probably. But would it have best the best-performing?

When it comes to the features of BTC and monetary management, it is possible that the existence of BTC as a reserve asset might actually have resulted in a collapse of the German economy in any event, but I don’t cover this very difficult set of arguments here. However, BTC as a reserve asset would likely not have stopped the rise of Adolph Hitler by ending the Great Depression early. In fact, the evidence shows that a devotion to hard money policies causes Great Depressions. As long as credit exists in an economy, is difficult to imagine a reserve currency without the flexibility for the central bank to act as lender of last resort. Bitcoin is not the answer to this problem. It couldn’t have solved the Great Depression and wouldn’t have prevented the rise of the Third Reich and the Second World War.

Deflation, rather than hyperinflation, contributed to the rise of Nazi Germany.

References and Further Reading

It is a sad fact that there is very little room in traditional economic thought for a thorough understanding of money and banking. The absolute best cure for any investment enthusiast or professional (the academy is stubbornly insular) is to audit my colleague Perry Mehrling's MOOC The Economics of Money and Banking on Coursera (but also available here: http://sites.bu.edu/perry/). I use his money pyramid and various money memes (e.g. "liquidity kills you quick") to explain finance to almost anyone, including high school students I mentor in Toronto. Finance professionals will love his book, The New Lombard Street (Princeton, 2013).

While much of the best academic economic history work is scattered throughout (generally paywalled) economic and history journals, I can recommend (1) Crafts and Fearon’s The Great Depression of the 1930s (Oxford, 2013) for the specialist and Barry Eichengreen’s Golden Fetters (Oxford, 1995) and/or Hall of Mirrors (Oxford, 2015) for their accessibility. Some other key works are Bernanke and Gertler “Inside the black box” (JEP, 1995) and Freidman and Schwartz's Monetary History of the US (Princeton, 1963), though I don't recommend buying the latter unless you need a very heavy doorstop.

As an antidote to Adam Fergusson’s When Money Dies: the Nightmare of the Weimar Collapse (Kimber, 1975) and Jens Parsson’s Dying of Money: Lessons of the Great German & American Inflations (Wellspring Press, 1974), I highly recommend Tobias Straumann’s 1931: Debt, Crisis, and the Rise of Hitler (Oxford, 2019).

Straumann’s link between austerity and Nazism is further detailed, and argued convincingly, in a fresh-off-the-press Galofre-Vila et al “Austerity and the rise of the Nazi party” (JEH, 2021). See also Haffert et al “Misremembering Weimar” (E&P, 2019).

Bernanke’s 2002 speech is here: https://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021108/

The prolific and popular Weimar expert Niall Ferguson has written on this exact topic in “Keynes and the German Inflation (EHR, 1995) and “Constraints and room for manoeuvre in the German inflation of the early 1920s” (EHR, 1996).