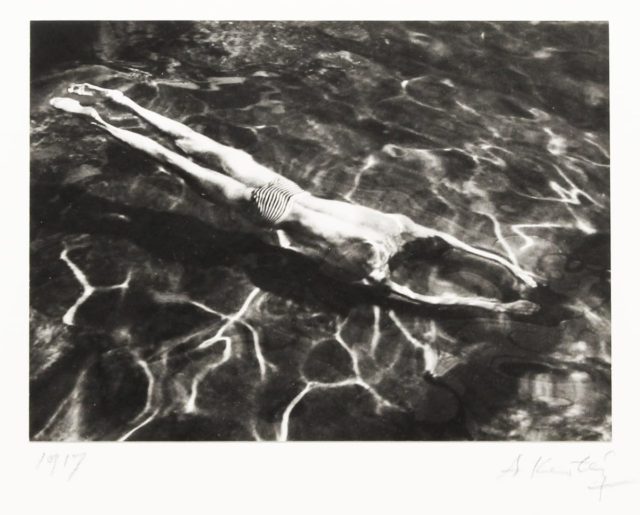

André Kertész (Hungarian, b. 1894)

Underwater Swimmer, August 31, 1917

Photograph

7 x 9.5 in

Gift of Walter Young MacDonald, Class of 1964

André Kertész is commonly attributed to the saying, “seeing is not enough, you have to feel what you photograph.” These words prompt an important question: Can one ‘feel’ a photo? Although there is no exact answer to this question, one can definitely ‘feel’ something while gazing through Kertész’s collection. Simple pictures of everyday life, riddled with the beauty of contrast and distortion, Kertész can show the viewer a snapshot of the world through his eyes.

Born in Budapest in 1894, Kertész bought his first camera in 1912 and used it to document the Austro-Hungarian war. He then moved to Paris, where his photography became more well known after he bought his first Leica and used it to photograph the streets of Paris. With his reputation and influence growing, he then moved to New York in 1936, where he worked for large magazines and as an independent photographer. During the 1960’s, Kertész’s personal photography was presented in solo exhibitions at venues such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1974.

Underwater Swimmer was taken in 1917, as Kertész recovered from a wartime injury that left his arm temporarily paralyzed. During the month it took to recover, Kertész used the extra time to photograph the world around him, and as a result gave us Underwater Swimmer, one of the first photographs using distortion and mirroring techniques.

Underwater Swimmer captures the moment a man dives into water; reflective light shimmering in the waves around him. The mechanics of the photo are deceptively simple–the ability to capture this exact moment, with no splashes or noise, shows the talent Kertész had with a camera even at an early stage of his career. The pool distorts the man’s figure, seemingly making his head and hands smaller than the rest of his body. These disproportions, the shadowing of the man, and the reflective streams of light in the pool all come together to make me feel as if I were there watching the man dive in with my own eyes.

Martha Tripsa ’24