Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Over the last four decades I have climbed on all seven continents. During that time it became apparent to me that Cerro Torre was the most magical mountain that I would ever encounter. A spike of light brown granite soaring over a vertical mile out of an ice sheet and capped by an otherworldly ice mushroom. Cerro Torre is also a peak of ever changing moods predicated by swirling storm clouds or an intense orange alpine glow on the rare clear days.

Cerro Torre also has a colorful history and therein lies the problem. In 1958 Walter Bonatti, the greatest climber of his generation, climbed to the Col of Hope on Cerro Torre’s southern flank and declared an ascent to the ice mushroomed summit impossible. A year later, Cesare Maestri arrived with Toni Egger and a support team to attempt the first ascent. During a six day period of stormy weather Maestri claimed to have completed the ascent of Cerro Torre with Toni Egger. During the descent Egger was swept away by an ice avalanche, along with their only camera, to the glacier below and his body disappeared, covered by fresh snow from the storm. Exultant with his success, Maestri crowed about his achievement and chided his rival Bonatti. Maestri said in referring to Bonatti’s ascent of the Col of Hope the previous year, “hope is the weapon of the weak, there is only the will to conquer.” Maestri had, with what now appears to be world-class hubris, named the col on his side of the mountain the Col of Conquest.

There was a great deal of skepticism about the ascent. A climb of such magnitude done in alpine style in such bad weather seemed unlikely given the state of the art of alpinism in 1959. When Maestri returned in 1970 with a veritable army, replete with a compressor powered bolt gun and sieged and bolted his way up the SW Ridge, he ignited a firestorm of protest. “A mountain desecrated,” roared the headline in Mountain Magazine. “How could a man who claimed to have climbed Cerro Torre in such impeccable style in 1959 come back and bolt his way to the top.” There were also defenders of Maestri, especially in Italy. Cesare had a formidable record of first ascents in the Dolomites and Egger was regarded as one of the best ice climbers of his time. As a young climber viewing these events from Camp 4, and three fourths Italian, I was a defender of Maestri’s, believing that a climber’s word was sacred.

In 1974 during my first trip to Patagonia I happened upon the remains of Toni Egger shortly after he melted out of the glacier that had entombed him for 15 years. I became obsessed with the idea of doing Cerro Torre’s immediate neighbor, which had been named in honor of Toni Egger. Torre Egger was unclimbed in 1975 and is still considered by many to be the most difficult summit to reach in the Western Hemisphere.

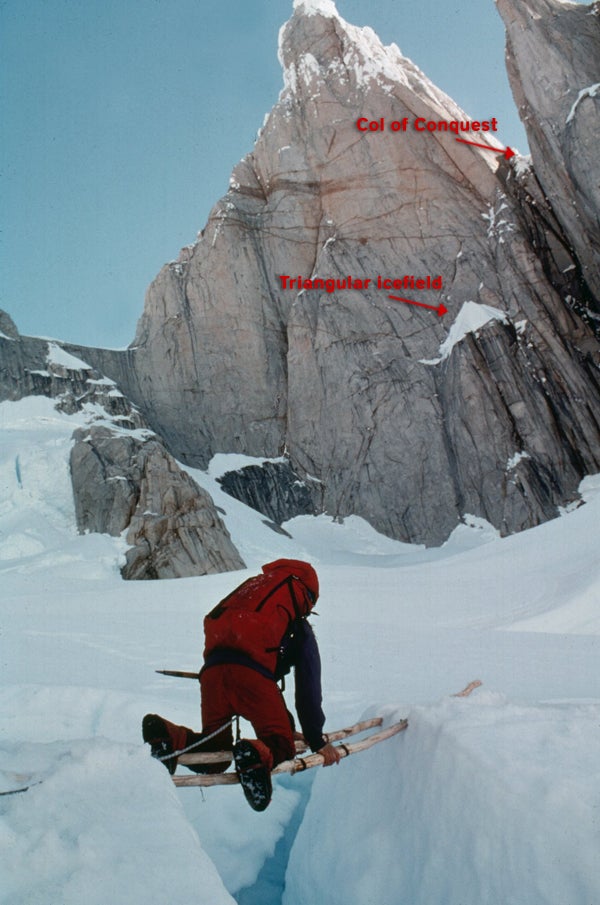

In 1975 I went to Patagonia with John Bragg and Jay Wilson to attempt the first ascent of Torre Egger. Our plan was to follow the footsteps of Maestri and Egger to the Col of Conquest and then climb the final 1400 ft. tower to Torre Egger’s summit mushroom.

There appeared to be three sections in the climb to the Col of Conquest: an initial 1000 feet of vertical climbing to a prominent triangular ice field, followed by 1500 feet of lower angled climbing, and, finally, a 400 foot traverse into the col. The traverse, from below, looked blank and vertical. What the hell, we reasoned, Maestri and Egger did it in 1959, and with our Yosemite experience we should be able to figure it out.

The climb started out as a trip through history. In the 1000 feet to the triangular ice field we were overwhelmed by the number of artifacts. Shards of rope, pitons, wooden wedges, and the odd bolt were found on nearly every pitch. The last pitch leading to the ice field was completely fixed with a bleached old rope that was clove-hitched to a piton and carabiner about every five feet. At the end of this pitch, just below the ice field and about a 1000 ft. up, we found an equipment dump left behind by Maestri and Egger. A brewing storm chased us down to the glacier and incessant storms over the next six weeks allowed us to speculate over the peculiar things that we had found.

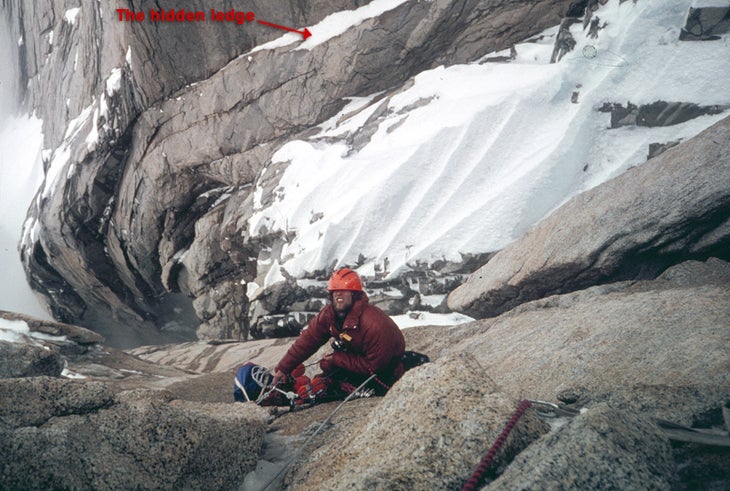

When the weather finally improved we went back up and made it to the Col of Conquest and finally on Feb. 23rd, 1976 to the summit. After seeing a hundred plus artifacts in the first 1000 feet we were surprised to find nothing, zero, zip, nada in the remaining 1500 feet to the col. No rap anchors or fixed gear, absolutely nothing. Suspicious, even damning, but not absolute proof that Maestri lied. What seals the case is the fact that Maestri described the route to the col as it appears from below and the actual climbing is quite different from his account. He recounted the first 1000 feet, which he undoubtedly did, as difficult, which it is. He described the 1500 foot lower angled section leading to the traverse into the col as easy and the blank looking traverse into the col he proclaimed difficult, requiring some artificial aid. The converse is true: The climbing to the traverse is more difficult than it appears and the traverse into the col, due to a hidden ledge system impossible to see until you are on top of it, is by far the easiest part of the climb. There is no doubt in my mind that Maestri did not climb Cerro Torre in 1959. I also am convinced that he didn’t make it to the Col of Conquest.

Why did I write this, isn’t everyone aware that Maestri lied? Apparently not, the Trento Film Festival (trentofestival.it) this May is hosting a program about the history of Cerro Torre. Given that this years festival coincides with the 50th anniversary of Maestri’s adventure it is not surprising the Maestri will get more credence than he is due.

Why do I care? Cerro Torre is one of this planet’s truly singular peaks and believing a climber’s account speaks to the heart of alpinism. In a little over a decade Maestri, it may be argued, perpetrated the greatest hoax in the history of alpinism and also desecrated Cerro Torre with the Compressor Route. While the route does have 18 pitches of real climbing on it, seven pitches of bolted climbing make it the worlds hardest via feratta. I should know, the weather prompted me to survive rather than summit. Cerro Torre deserves better. If the West Face (one of the world’s premier ice climbs) were the easiest route, which would be the case without the Compressor Route, Cerro Torre would surely be a mountain whose difficulty matched its beauty.