Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Human remains displayed as though they were hunting trophies. Pets encouraged to play with or among body parts. Art made from what was once a person.

Throughout their research in human remains trafficking, professor Shawn Graham and Dr. Damien Huffer have seen it all.

Huffer is a scholar with research ties to Carleton University in Canada and the University of Queensland in Australia, while Graham is a professor of digital humanities at Carleton. Their work has tracked the sale of human remains in the digital age, from bones on TikTok to fetuses in jars on Instagram.

“Different collectors occupy different niches,” Graham and Huffer told Boston.com in a joint email interview. “For any category of human remains you can imagine, someone has collected it, wants to sell it, is selling it, or would buy it if they find it for the right price.”

This so-called “red market” made national headlines last week after a former Harvard Medical School morgue manager, his wife, and several others were charged in an alleged scheme to steal and sell body parts.

The Harvard morgue scandal shed light on the morbid collectors who seek to own bits and pieces of other people. Meanwhile, it’s also left experts pondering potential repercussions for one of the most fundamental learning tools in medicine: Donated cadavers.

In court documents packed with grisly details, prosecutors alleged a sprawling conspiracy to steal and sell human remains from the HMS morgue and from an Arkansas mortuary. Bones, skin, heads, organs, genitals, and whole stillborn corpses were among some of the human remains allegedly up for sale.

But what draws some people to collect someone else’s body parts?

“In our research, we often find that what people say about why they collect human remains is at odds with what they actually do with the human remains,” Graham and Huffer said. “People will say that they are collecting remains so that they don’t languish in a museum, so that they can be appreciated and ‘learned from,’ which begs the question, by whom?”

The human remains trafficking experts said they often see the defense “Oh, not all collectors!” on the various platforms they monitor.

However, they said, “When you look at the large scale patterns in how people talk about what they’ve collected (on the order of tens of thousands of posts), and you look at large scale patterns in how they photograph or display them, it’s quite clear that having control over other people as represented by human remains is a strong latent factor in this trade writ large.”

The practice of collecting human remains goes back centuries.

“Starting around the time of the Civil War and stretching deep into the 20th century, gathering human skeletal remains was a common intellectual, cultural and social pursuit,” as Smithsonian magazine notes.

But in the digital era, “Social media removes the middleman, and supercharges the ability of collectors and people willing to sell to find each other,” Graham and Huffer explained. “It enables some people to actually make a living trading the remains of other people.”

Several online platforms — Facebook, Instagram, Etsy, and eBay included — have policies banning the sale of body parts or human remains, but they don’t always work as intended.

“Social media platforms just don’t want to know,” Huffer and Graham said. “Many vendors will include the pertinent information for making a sale within the images themselves that they post, which the moderation — such as it is — doesn’t catch.”

Vendors and collectors might also skirt the rules by using one platform to advertise their “wares” while completing deals on another site, they explained.

Meanwhile, without a federal law forbidding the transfer or possession of human remains (unless the remains are Native American), the trade is left to flourish in the gray areas formed under a patchwork of state laws.

The market for human cadavers intended for education and research, largely unregulated at a federal level, is another story.

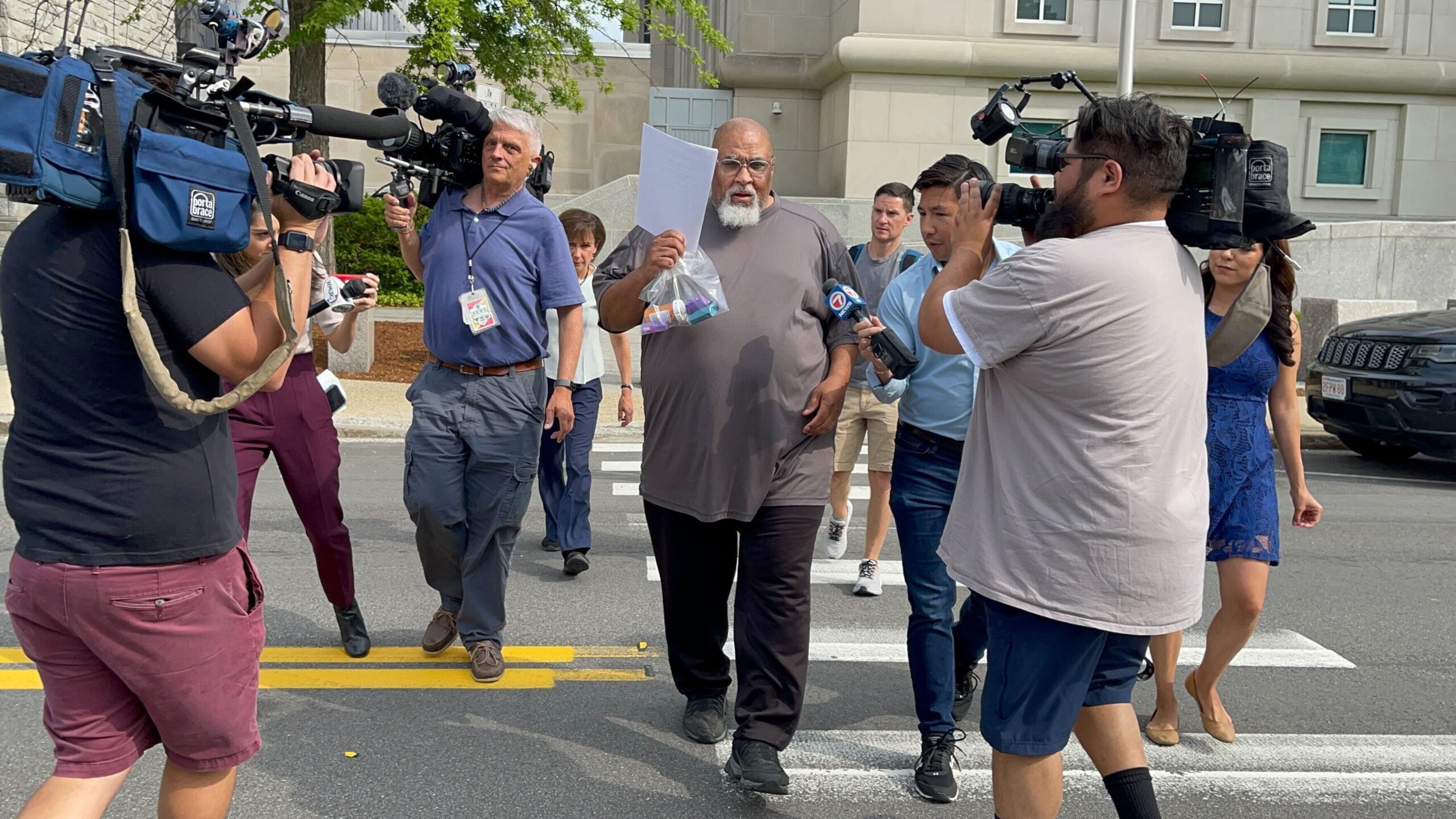

Family members who believe their loved ones’ body parts may have been stolen from Harvard Medical School’s morgue have begun speaking out, with one donor’s son even filing a class-action lawsuit against Harvard and former morgue manager Cedric Lodge last week.

What does that mean for future donations?

“The allegation against those involved in the sale of body parts from Harvard Medical School’s donation program are extremely troubling. If proven true, the sale of body parts is not only illegal, but most importantly, truly horrific for those who trusted the school to properly handle their remains,” Michel Anteby, professor of management and organizations at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business, said in an email interview.

“This, of course, will likely impact people’s immediate willingness to donate their bodies to this specific program,” said Anteby, who has studied the supply and demand of cadavers for medical education and research in the U.S.

Anteby suspects that the Harvard morgue scandal may not upend individuals’ decision to donate their bodies, though they might consider other anatomical gift programs in Massachusetts — at least until Harvard Medical School “can reassure them that the alleged illegalities will never happen again.”

He added: “My expectation therefore is that the overall supply of cadavers will remain stable, even if some donations end up in the short-term going elsewhere.”

There are ways for institutions to more securely track and handle donated cadavers throughout the process, Anteby explained, holding up the University of California’s transparent policies and procedures as one example.

Some programs, like the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s, implant a radio-frequency identification (RFID) chip in cadavers for tracking, while others track the weight of final cremated remains to match it with the donor’s expected output, Anteby explained.

“While the above-cited measures can increase the security and traceability of donated specimens, donation programs ultimately rely on their staff’s professionalism to ensure the proper running of their operations,” he added.

Harvard hasn’t explained the level of monitoring and oversight it had over bodies donated for education and research purposes, The Boston Globe has pointed out.

However, in a letter to donors’ next of kin last week, Harvard Medical School Dean George Q. Daley described an “enormous respect and gratitude” for donors and a “deep reverence” for the process of dissection.

“Learning anatomy transforms students from pre-meds to physician-healers; it is an experience that changes your heart and soul, forever,” Daley wrote. “Those values are passed down every fall to our new students who, each year at the conclusion of their studies, hold a poignant, private memorial service to honor the donors.”

When human remains are bought and sold, an element of humanity is lost, Huffer and Graham explained.

“Ask yourself if you would be OK with someone buying/selling your grandmother’s skull,” the experts said. “Now imagine you are from a culture where human remains are venerated as Ancestors: to buy and sell, to commodify these remains not only dehumanizes but is an active crime against the living.”

Ultimately, they added, “the trade reduces human lives lived to mere ‘things’; passing through the hands of dealers for profit only adds insult to injury. The human remains trade is an affront to human dignity.”

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com