On a Friday evening in late 1998, moviegoers settled into their seats at a Northern California cinema for the Will Smith blockbuster Enemy of the State. In the movie, Smith plays Dean, a lawyer in D.C. who comes into possession of a video linking a rogue cell at the National Security Agency to the murder of a congressman.

The NSA’s relentless effort to hunt Dean down and retrieve the tape is, in a way, an old yarn—about power’s vicious impulse to stamp out any challenge to its standing. What’s new are all the gadgets at this modern Goliath’s disposal.

The agency bugs Dean’s house with tiny cameras, taps his phones, and plants trackers in his clothes. The moral is clear: Modern surveillance technology makes power all the more vicious and rigs the contest between the strong and the weak so thoroughly that there is really no contest at all.

No single weapon in the movie embodies this quarrel more persuasively than the NSA’s gigantic spy satellite, which glares down on what seems like the entire Eastern Seaboard. It’s terrifying to behold. But for one man in that Northern California cinema, out on a date with his wife, watching the satellite track Dean’s every frantic, hopeless step had the opposite effect.

By day, he was an engineer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a secretive government research facility about an hour from San Francisco. As such, he knew that the Enemy of the State satellite was pure fantasy. But what if it could be willed into existence? He wondered. The movie makes it resoundingly clear that it would be very bad for all of us if such a cruel device did, in fact, exist—but this must not have registered. As the credits rolled, he rushed home and left a breathless message with his supervisor: “I have a great idea. Call me.”

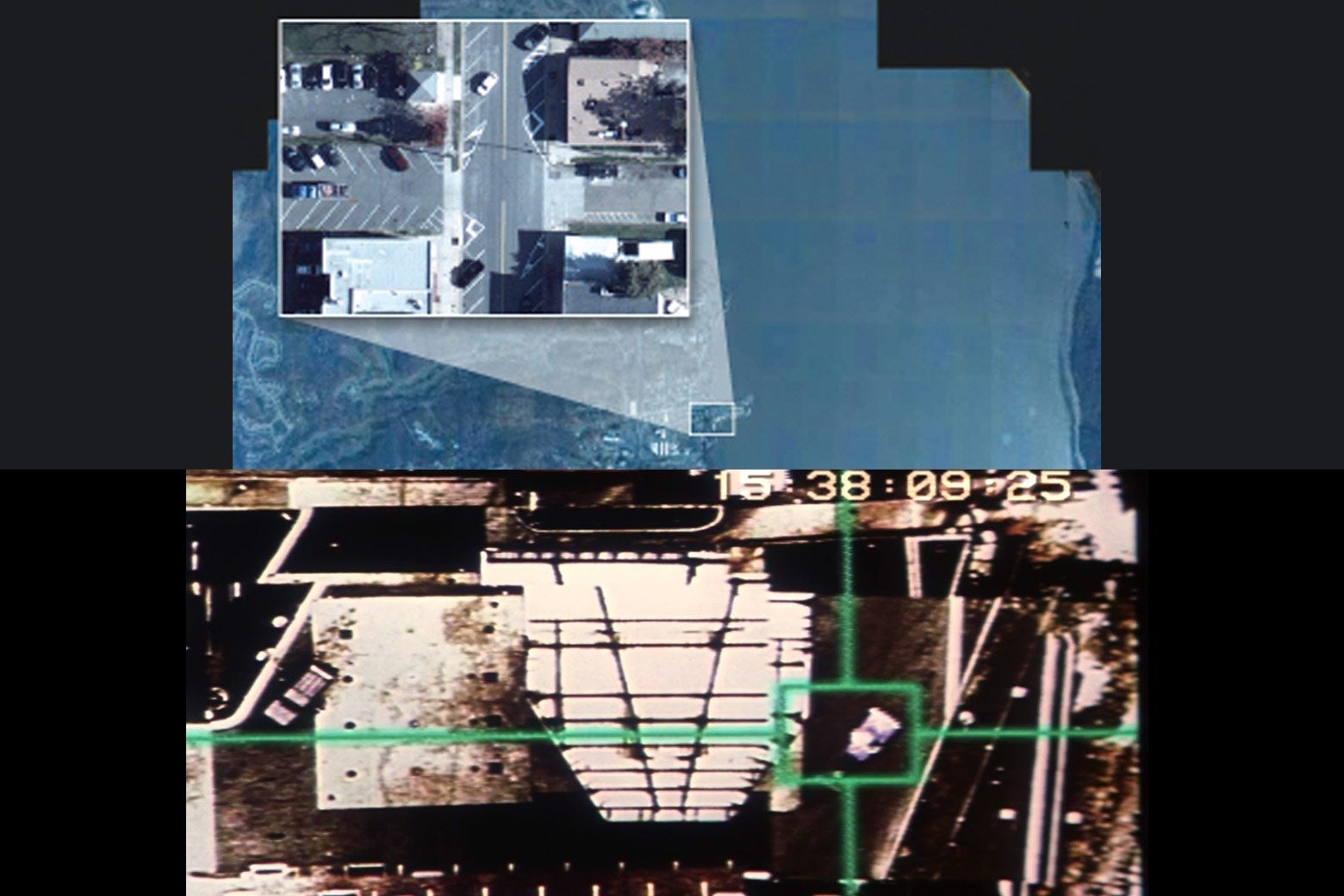

This kicked off a secret weapons development program, the full account of which had never been told until now, that made real what Enemy of the State had only imagined. An airborne camera capable of watching city-size areas, tracking thousands of vehicles and people simultaneously. It is known as wide-area motion imagery—WAMI (pronounced whammy) for short. I just call it the all-seeing eye.

With enthusiastic backing from the CIA, it was first deployed in the 2000s to hunt down insurgent groups in Iraq. Since then, all-seeing surveillance cameras have also been employed extensively in Afghanistan, Syria, and other undisclosed battlefields.

Now, numerous defense firms are peddling the technology to law enforcement departments around the U.S. Some of its most dangerous features are also trickling down into other surveillance tools, including your neighborhood CCTV.

It is, in other words, coming home—to watch us in our own cities, to possibly even stamp down those who, like Dean, might otherwise speak truth to power—and we are woefully ill-prepared to face it. Even though it was all foreseen in a movie that came out 21 years ago.

The all-seeing eye’s journey from silver-screen conceit to battlefield reality is not as unlikely as you might think. The government has always seen movies as a reliable source of ideas.

Engineers at DARPA, the future-making Department of Defense research and development lab, have borrowed from Blade Runner (the first one) and Avatar, among other sci-fi classics. In 2011, a staff sergeant for the Iowa National Guard, inspired by Jesse Ventura’s ammo backpack in Predator, designed a kit to allow a single soldier to handle the two-person Mk 48 machine gun. For some Pentagon groups, engineering from fantasy has become a matter of policy. The Army and the Marine Corps regularly enlist science fiction writers to help build visions for combat in the mid–21st century.

There are, no doubt, other ongoing weapons programs yet to be revealed that are similarly drawn from movies we all love to watch—and then forget. Like Enemy of the State, many of those movies probably forewarn that the technology they have inadvertently inspired would be dangerous.

And like the groups involved in the effort to re-create the satellite from Enemy of the State, the engineers behind these programs will understand that those movies are meant to be cautionary tales but ultimately decide that the technology’s dangers do not outweigh its gains.

It is not as though the government doesn’t know how to heed Hollywood’s warnings. When Ronald Reagan, an avid sci-fi fan, watched the movie WarGames, about a teenager who hacks into America’s nuclear command and control software, he ordered the top brass at the Pentagon to study whether such an attack would actually be possible. They found that it could, leading to a raft of policy changes, some of which continue to protect us (on paper at least) today. But sometimes, when movies’ warnings are less convenient, they will go unheeded.

For its part, Hollywood can’t be expected to abstain from dreaming up terrible machines, though it isn’t entirely irreproachable either. Just as the Pentagon often helps Hollywood make war movies (on the condition that they’re not too critical), Hollywood isn’t shy about helping the Pentagon turn fiction to fact.

Following the 9/11 attacks, for example, the Pentagon convened two dozen screenwriters, including Steve de Souza, who wrote Die Hard and Die Hard 2, for input on what al-Qaida might be planning next and what to do about it. By all accounts of the confidential gathering, the movie types were full of ideas, and the military types took copious notes.

Hollywood even played a starring role in the development of the all-seeing eye. When Livermore set out to replicate the Enemy of the State satellite, it hired some of the very people who had created the fictional aerial surveillance footage for the movie—which they had cleverly achieved with a helicopter and an airborne camera system that won an Oscar in 1990 for its stability and precision. (The same technology is now used aboard spy planes the world over.)

The author of WAMI’s global technical standards, Rahul Thakkar, is a celebrated engineer in the movie industry. He was part of the team that gave us Shrek. He has an Oscar too. As does PV Labs, an important Canadian WAMI maker that has surveilled the unwitting residents of several U.S. and Canadian cities using a technology that was behind the aerial shots in The Dark Knight Rises. Without movie types to help it along, WAMI’s story might have turned out very differently.

The cross-pollination between the Pentagon and Hollywood might therefore deserve a little more scrutiny, especially now that so many of sci-fi’s most preposterous ideas are just one good algorithm away from actually becoming a waking nightmare. In a twist that even Enemy of the State’s writers didn’t dare dream, the all-seeing eye is being paired with artificial intelligence so that it can “predict” crimes before they happen. There’s a movie about that, too. It’s called Minority Report.

So, next time you’re watching a dystopic thriller full of vicious imagined gadgets, take note. You might find it frightening, but someone else in the audience with the resources to turn fantasy to reality could very well find it so inspiring that he will rush home to make that fateful call: “I have a great idea.”

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.