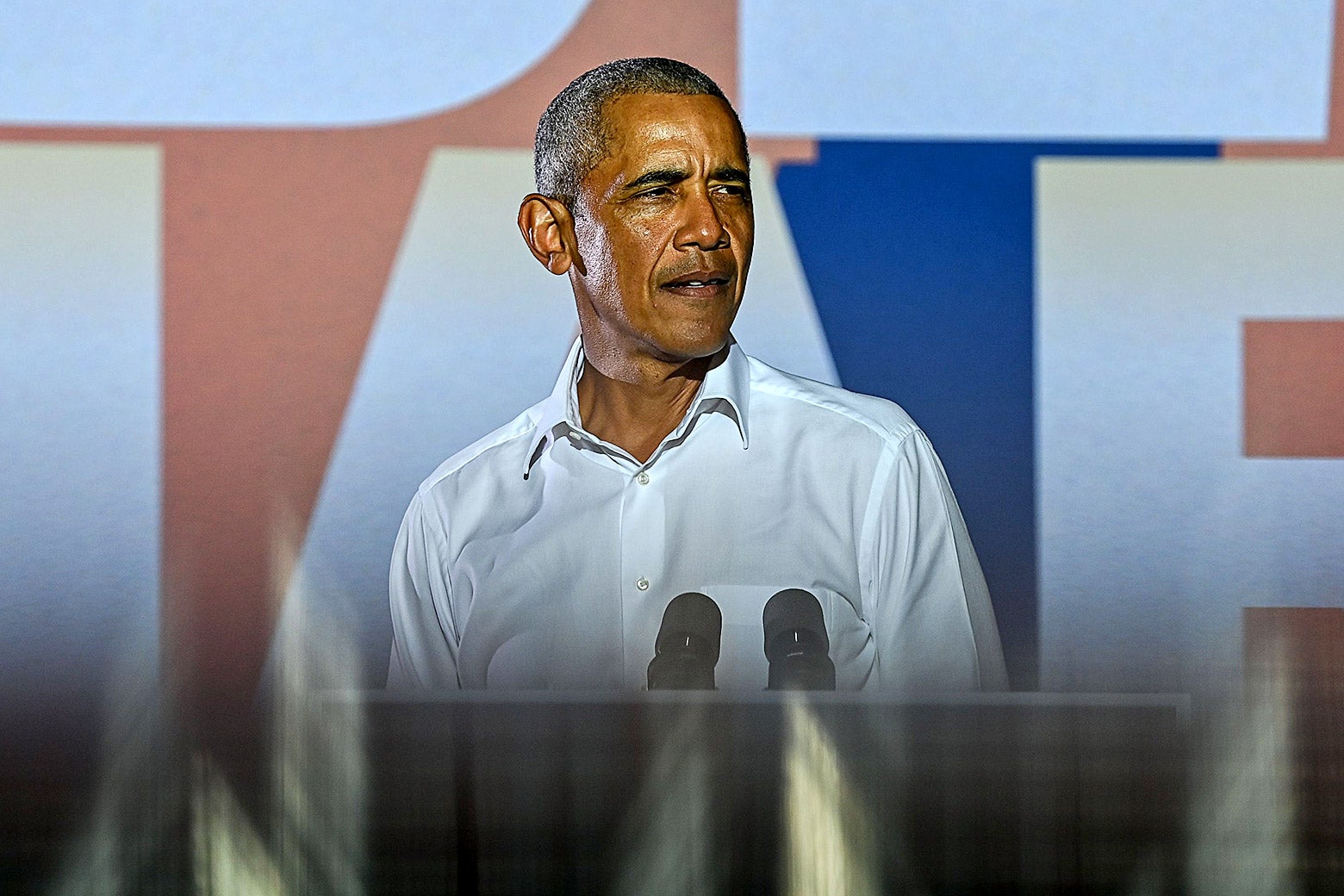

Barack Obama is ready to come back into the spotlight. After four years spent mostly out of the public eye, right on the heels of Donald Trump’s defeat, the ex-president is suddenly everywhere. He’s on the Tonight Show weighing in on whether Chicago deep-dish or New York–style pizza is better. He’s slamming the Knicks on Desus & Mero and deep in conversation with Oprah on Apple TV+. He’s talking books with Michiko Kakutani in the New York Times and lamenting, to Stephen Colbert, that he forgot to give Dolly Parton a Presidential Medal of Freedom—but don’t worry, he’ll just “call Biden.” He’s arguably taking up media oxygen that might otherwise be going to the newly elected president whose inauguration remains absurdly disputed. He is almost unavoidable.

And while Obama hasn’t changed, something has. The charm and ease that made him a political star in 2004 is landing a little differently now that the line that used to divide “celebrity” and “statesman” has blurred to a noxious smear. Whatever relief and nostalgia many felt when Obama spoke at the Democratic National Convention—finally, he was back!—is leaching out as it becomes apparent that the man still thinks “star” and “ex-president” can be massaged into complementary identities. And so, while Trump and an astonishing number of high-ranking GOP members do everything in their power to overturn the results of the election in the middle of a pandemic that is killing almost 3,000 Americans a day, Obama’s out and about selling his new memoir, joshing around with TV hosts, and burnishing an enormously profitable personal brand. It was when news broke that he and Michelle Obama’s production company will make a show about how Trump botched his transition to becoming president that would be “part-documentary, part-sketch comedy” that something started to rankle. For one thing, we’re currently stuck in a second catastrophic Trump transition. For another, while his missteps were legion, they weren’t particularly funny to those affected by them, or for those who were around to fight them—which Obama absolutely wasn’t.

His absence was keenly felt. After Trump’s inauguration, Obama disappeared from public view for so long that it became, in internet parlance, a Thing. Everyone wondered about it: “Where is Barack Obama?” Gabriel Debenedetti wrote back in 2018, when desperate Democrats were trying to mobilize for the midterms, that Obama had “only agreed to hold three fund-raisers for Democratic groups this summer after fielding months of requests.” It was arguably worse than that: Democratic Party operatives discovered that they were in effect competing with Obama for donations—he was fundraising for his foundation and getting to donors in Silicon Valley and elsewhere first. They were tapped out by the time Democrats got to them. As one fundraiser put it, “Nobody expects him to be out there bashing Trump or being on the campaign trail every day. But to be sucking up resources now is just tone-deaf, and self-serving.” In June of 2020, some sources near Obama suggested to the New York Times that Obama’s broader absence during the campaign might represent an effort to “avoid overshadowing the candidate” (though, judging from his conduct now, it doesn’t seem like overshadowing Joe Biden is a particular concern).

Many defended him, and they had a point. For one thing, Obama deserved a break after eight years of presidential work under unrelenting Republican obstructionism. For another, it seems he modeled his post-presidential conduct on his own predecessor, George W. Bush—who remained decorously silent about his successor’s priorities and initiatives. But perhaps most clearly, his absence made strategic (and public-spirited) sense; if Trump was a backlash to Obama, Obama’s presence as a foil for Trump to inveigh against could only make matters worse. Keeping his powder dry seemed wise, and it counted when he used it: The Obamas were a galvanizing force when they showed up at the DNC.

But in these recent appearances, the most surprising thing might be that his political remarks about this moment feel stale. Maybe his absence from the fray over these past four years has cost him. Maybe he’s using a different timescale to measure progress (as he sometimes explicitly says he is). But even his harshest remarks about the right don’t capture the hysterical party we’re watching try to steal an election. His recent criticisms of “snappy” leftist political slogans like “defund the police” reflect an abiding faith in a theory of politics that seems passé—as several Black intellectuals and activists have pointed out. Boiled down to its essentials, Obama’s argument is that one shouldn’t “alienate” people who might be converted to your cause if you say things in just the right way. In practice, that means tucking the political self into a package that a “reasonable person”—that usefully unmeasurable political fiction—cannot help but find acceptable and persuasive.

Obama’s personal self-packaging has long been extraordinary. He won two elections with it. But he also disproved his own theory. Despite his extraordinary efforts to perform an unoffending normalcy, he was spectacularly mischaracterized as a socialist, a Kenyan, a Muslim, a criminal, and more. He was demonized by an opposition party whose virulent determination to shove evidence aside has only grown since—they will read Biden as a communist pedophile and Trump as an athletic man of God. This is not an environment where self-editing or careful packaging matters. Nor is it one where bland political slogans gain purchase.

Obama’s commitment to not alienating people is fascinating to the precise extent that it becomes a principle in its own right. It explains, I think, why there’s something so mystifyingly generic about his self-presentation when you take him out of the right-wing fever swamp. His music selections could be a Starbucks album, they’re so mainstream. Asked what someone should read to understand this bizarre, unprecedented moment in contemporary America, he recommends the fresh unplumbed perspectives of de Tocqueville and Thoreau. In other words: Obama sat the last four years out and it shows. He might be appearing on “Snapchat political shows,” but his ability to adapt to new media forms does not extend to his political thinking. He isn’t bringing new tools or interpretations to the table and he seems to be overlooking the extent to which older tools do not work.

I only partially intend this as a criticism. It has long been the case that white men are permitted eccentricities and excesses that women and minorities are not. Trump can get away with insulting Gold Star families for the same reason Obama got attacked for saluting the Marines while holding a coffee cup. Obama’s compulsive reaffirmations of old American texts and principles feel related: As the first Black president, Obama had to constantly project so high and painful a pitch of normalcy and competence that the invisible constraints he worked under in some ways resemble those Queen Elizabeth II struggles with in Netflix’s The Crown. The show explores how a figure laboring under the representative burden of “the State” must edit personality out of her personality, file herself down to a blandness suitable to a nation’s needs and functions.

It is to his credit that he managed to have a personality anyway! Charisma comes in many forms, and it usually manifests as some kind of excess. And so Obama wasn’t normal; he was normal-plus: He was funny. He was athletic. He had comic timing. His roasting of Donald Trump was so good it was also, according to some, disastrous. And his discipline about his image was so strong that he managed to walk a very fine line indeed: He was a nerdy professor of constitutional law with normie tastes, but he was also “cool.” The brand worked in part because it was so fine-tuned and stage-managed. During his presidency, the Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan correctly criticized Obama for what she calls “Transparency Lite”: “He did tons of interviews, but many of them involved celebrity conversationalists who pitched softball questions. During a visit to Vietnam, he chatted with Anthony Bourdain, the globe-trotting TV chef. He got raves for his interview with the comedian Zach Galifianakis on the faux talk show Between Two Ferns. … Great for brand-building. Not so great for serious accountability.” And for all that Obama’s memoir is “presidential” and therefore quite serious, his new ubiquitous presence feels like a celebrity’s because he’s acting like one—accepting invitations and interviews that are friendly and avoiding tough questions.

The first time Obama publicly mentioned Trump after leaving office was in September 2018, in a speech he delivered at the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign. This was 20 months into the latter’s presidency, two months before the midterm election. Obama described Trump as a “symptom” of the “politics of fear and resentment and retrenchment.” He characterized the upcoming vote as the exceptional emergency it was: “Just a glance at recent headlines should tell you that this moment really is different. The stakes really are higher. The consequences of any of us sitting on the sidelines are more dire.” But, despite this admonishment, he remained on the sidelines himself.

Maybe all post-presidencies are unattractive. George W. Bush mostly vanished, surfacing only to show paintings that hinted a little obviously at introspection. One has only to read Vanity Fair’s evisceration of Bill Clinton’s post-presidential life (as narrated by his former “body man” and confidant Doug Band) to lose respect for employer and employee alike. An ex-president can be a needy and grubby thing, and the optics of an ex-president might be harder to wrangle than the presidency itself. Obama stayed away during the Trump years. Maybe he deemed it tactically wise. Maybe he was tired. Maybe he wanted to work on his foundation. But we could have used him during these four awful years. And it doesn’t feel great to see him everywhere now that there’s finally some hope of repair—genial, joking, and ready to, of all things, produce a TV show about Donald Trump.