Everything you think you know about one of the most famous photographs in history is wrong.

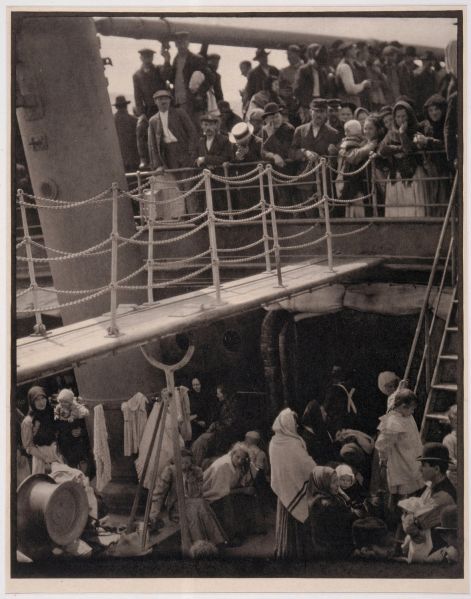

Alfred Stieglitz’s 1907 The Steerage is famous around the world as perhaps the classic representation of the 20th-century immigrant arriving in America from Europe for the first time. In the decades since it was taken, the photo has become inextricably tied up with the immigrant journey.

Yet Rebecca Shaykin, curator of “Masterpieces & Curiosities: Alfred Stieglitz’s The Steerage” at the Jewish Museum through February 14, points out that our understanding of the photograph is largely misinformed.

When Stieglitz took the photograph, he was actually on board a ship heading east toward Europe—dashing any possible tales of the vessel gliding historically into Ellis Island. In other words, those pictured were most likely people who had been denied entry to the U.S. and were forced to return home. Moreover, a man who appears, at fast glance, to be in a tallit, or Jewish prayer shawl—a detail which has made the image a touchstone in the Jewish community for decades—is actually a woman in a striped cloak.

Given the enduring power of the image, these details are somewhat immaterial, however. “It’s very clear that this image, and Stieglitz being a Jewish photographer, is very important to Jewish history and Jewish culture,” Ms. Shaykin told the Observer during a walkthrough of the show. “[In his memoir] he tells the story about how he came and saw the steerage class passengers on the boat. He felt a natural affinity to them. He doesn’t outright say it’s because, as a son of German-Jewish immigrants, he felt some sort of kinship to them, but it’s implied.”

In Stieglitz’s own account, he described traveling with his daughter and first wife, Emily, whom he described as more decadently inclined than himself. “My wife insisted on going on the Kaiser Wilhem II—the fashionable ship of the North German Lloyd at the time,” the photographer lamented of the journey. “How I hated the atmosphere of the first class on that ship! One couldn’t escape the nouveaux riches.”

On the third day, Stieglitz claimed, he couldn’t stand it any longer and took a walk to the ship’s steerage where, compelled by the people below and geometric architectural structures he saw, he ran to grab his camera.

‘If all my photographs were lost, and I’d be represented by just one, ‘The Steerage’…I’d be satisfied.’

“Spontaneously I raced to the main stairway of the steamer, chased down to my cabin, got my Graflex, raced back again.” (The exhibition text quotes his story of the account.) “Would I get what I saw, what I felt? Finally I released the shutter, my heart thumping. I had never heard my heart thump before. Had I gotten my picture? I knew if I had, another milestone in photography would have been reached.”

The Steerage is one of several visual milestones of the immigrant experience selected by the Jewish Museum for “Masterpieces & Curiosities”—described by the museum as a series of intimate “essay” exhibitions. Previous pieces, for example, have included a Russian Jewish immigrant family’s quilt, circa 1899, and Diane Arbus’ famed Jewish Giant, photographed in 1970.

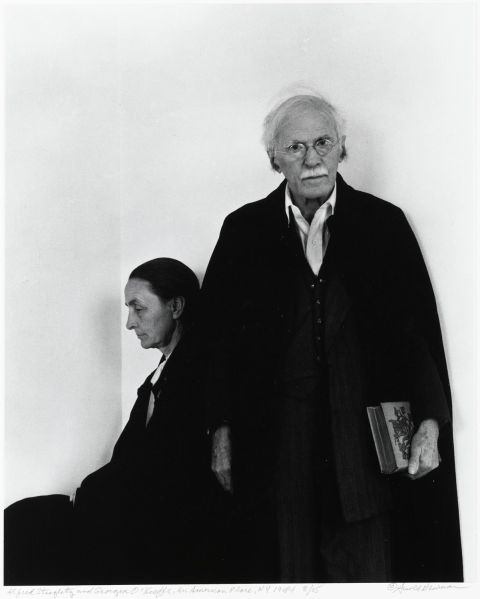

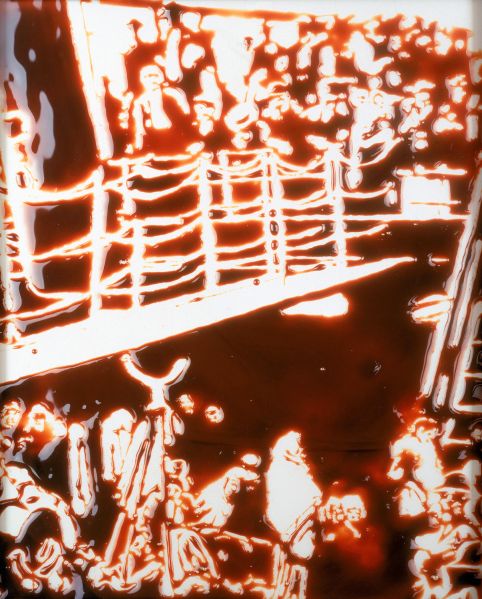

For The Steerage, the museum has suspended the image in a glass vitrine alongside two related pieces of artwork: Vik Muniz’s 2000 appropriations of Stieglitz’s photograph in chocolate sauce, and Arnold Newman’s 1944 double portrait of Stieglitz and his second wife, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe. In addition, there is also a small-scale replica of the Kaiser Wilhem II and various ephemera, such as postcards that were sold on board the ship.

To the left of The Steerage, a cluster of reproductions of the photograph are on display. There is a 1911 issue of Camera Work, edited by Stieglitz himself, a 1944 Saturday Evening Post profile by Thomas Craven titled “Stieglitz—Old Master of the Camera” and Alfred Kazin’s memoir. The critic, himself the son of Polish-Jewish immigrants, both owned a print of the work and used it as a frontispiece in his memoir A Walker in the City. The picture has enjoyed numerous reproductions, even appearing on the cover of a recent textbook titled The Columbia History of Jews and Judaism in America.

“Just reproducing the images over and over again, they become part of the popular imagination,” said Ms. Shaykin. “It’s interesting to me that the first time he published it was in 1911—there was a very select group of people who cared deeply and passionately about Modern art at this time. Then, nearly 20 years after he took it, 1924, he’s reproducing it in Vanity Fair, and then again in The Saturday Evening Post toward the end of his life. He’s really pushing his work—that image in particular—into the world to become quite popular.” (The Vanity Fair reproduction was, rather misguidedly, printed alongside a satirical advice column titled “How to be Frightfully Foreign.”)

Stieglitz made no effort to hide his intentions. “If all my photographs were lost, and I’d be represented by just one, The Steerage,” he said near the end of his career, “I’d be satisfied.”

As for Ms. Shaykin, she hopes viewers will walk away understanding where Stieglitz was coming from. The photographer may have been traveling in the lap of luxury, but he chose to photograph, and document for decades to come, the travelers on a very different journey.

Like happens so often, she said, “[The photograph] has really had a life of its own beyond the original intention of the artist.”